Sudan

Republic of the Sudan جمهورية السودان (Arabic) Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān | |

|---|---|

Flag  Emblem | |

Motto: النصر لنا (Arabic) "An-Naṣr lanā" "Victory is ours" | |

Anthem: نحن جند الله، جند الوطن (Arabic) Naḥnu Jund Allah, Jund Al-waṭan We are the Soldiers of God, the Soldiers of the Nation | |

Sudan in dark green, disputed regions in light green. | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Khartoum 15°38′N 032°32′E / 15.633°N 32.533°E / 15.633; 32.533 |

| Official languages |

|

| Religion | Islam |

| Demonym | Sudanese |

| Government | Federal dominant-party presidential republic (de jure) Federal one-party state under a totalitarian dictatorship (de facto)[2] |

• President | Omar al-Bashir |

• Prime Minister | Motazz Moussa |

• First Vice President | Bakri Hassan Saleh |

• Second Vice President | Hassabu Mohamed Abdalrahman |

| Legislature | National Legislature |

• Upper house | Council of States |

• Lower house | National Assembly |

| Formation | |

• Sultanate of Sennar | 1504[3] |

• Egyptian conquest of Sudan | 1820-74 |

• Anglo-Egyptian Sudan | 1899 |

• Independence | 1 January 1956 |

• Current constitution | 9 January 2005 |

• Secession of South Sudan | 9 July 2011 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,886,068 km2 (728,215 sq mi) (15th) |

| Population | |

• 2016 estimate | 39,578,828[4] (35th) |

• 2008 census | 30,894,000 (disputed) [5] |

• Density | 21.3/km2 (55.2/sq mi) |

GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $197.825 billion[6] |

• Per capita | $4,700[6] |

GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $138.090 billion[6] |

• Per capita | $3,459[6] |

Gini (2009) | 35.3[7] medium |

HDI (2017) | low · 167th |

| Currency | Sudanese pound (SDG) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +249 |

| ISO 3166 code | SD |

| Internet TLD | .sd سودان. |

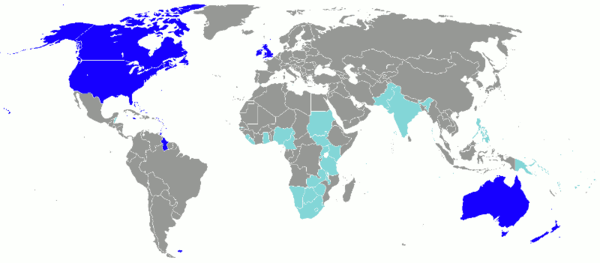

Sudan (US: /suˈdæn/ (![]() listen), UK: /suˈdɑːn, -ˈdæn/;[9][10]Arabic: السودان as-Sūdān), officially the Republic of the Sudan[11] (Arabic: جمهورية السودان Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea to the east, Ethiopia to the southeast, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, and Libya to the northwest. It houses 37 million people (2017)[12] and occupies a total area of 1,861,484 square kilometres (718,722 square miles), making it the third-largest country in Africa.[13] Sudan's predominant religion is Islam,[14] and its official languages are Arabic and English. The capital is Khartoum, located at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile.

listen), UK: /suˈdɑːn, -ˈdæn/;[9][10]Arabic: السودان as-Sūdān), officially the Republic of the Sudan[11] (Arabic: جمهورية السودان Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea to the east, Ethiopia to the southeast, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, and Libya to the northwest. It houses 37 million people (2017)[12] and occupies a total area of 1,861,484 square kilometres (718,722 square miles), making it the third-largest country in Africa.[13] Sudan's predominant religion is Islam,[14] and its official languages are Arabic and English. The capital is Khartoum, located at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile.

Sudan's history goes back to the Pharaonic period, witnessing the kingdom of Kerma (c. 2500 BC-1500 BC), the subsequent rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom (c. 1500 BC-1070 BC) and the rise of the kingdom of Kush (c. 785 BC–350 AD), which would in turn control Egypt itself for nearly a century. After the fall of Kush the Nubians formed the three Christian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia, with the latter two lasting until around 1500. An influx of Muslim Arabs who had already conquered Egypt, eventually controlled the area and replaced Christianity with Islam. During the 1500s a people called the Funj conquered much of Sudan. From the 16th–19th centuries, central and eastern Sudan were dominated by the Funj sultanate, while Darfur ruled the west and the Ottomans the far north. This period saw extensive Islamization and Arabization.

From 1820 to 1874 the entirety of Sudan was conquered by the Muhammad Ali dynasty. Between 1881 and 1885 the harsh Egyptian reign was eventually met with a successful revolt led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad, resulting in the establishment of the Caliphate of Omdurman. This state was eventually destroyed in 1898 by the British, who would then govern Sudan together with Egypt.

The 20th century saw the growth of Sudanese nationalism and in 1953 Britain granted Sudan self-government. Independence was proclaimed on January 1, 1956. Since independence, Sudan has been ruled by a series of unstable parliamentary governments and military regimes. Under Gaafar Nimeiry, Sudan instituted fundamentalist Islamic law in 1983.[15] This exacerbated the rift between the Arab north, the seat of the government and the black African animists and Christians in the south. Differences in language, religion, ethnicity and political power erupted in a civil war between government forces, strongly influenced by the National Islamic Front (NIF) and the southern rebels, whose most influential faction was the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), eventually concluding in the independence of South Sudan in 2011. Before the Sudanese Civil War, South Sudan was part of Sudan, but it became independent in 2011.[16] Since 2011 Sudan's government is engaged in a war with the Sudan Revolutionary Front. Human rights violations, religious persecution and allegations that Sudan had been a safe haven for terrorists isolated the country from most of the international community. In 1995, the United Nations (UN) imposed sanctions against Sudan.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Prehistoric Sudan (before c. 800 BC)

2.2 Kingdom of Kush (c. 800 BC–350 AD)

2.3 Medieval Nubian kingdoms (c. 350–1500)

2.4 Islamic kingdoms of Sennar and Darfur (c. 1500–1821)

2.5 Turkiyah and Mahdist Sudan (1821–1899)

2.6 Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956)

2.7 Independence (1956–present)

2.7.1 1990s–2000s

2.7.2 Partition and rehabilitation

3 Geography

3.1 Climate

3.2 Environmental issues

4 Government and politics

4.1 Sharia law

4.2 Foreign relations

4.3 Armed Forces

4.4 International organizations in Sudan

4.5 Human rights

4.5.1 Darfur

4.6 Disputed areas and zones of conflict

4.7 Administrative divisions

4.8 Regional bodies and areas of conflict

5 Economy

6 Demographics

6.1 Ethnic groups

6.2 Languages

6.3 Urban areas

6.4 Religion

7 Culture

7.1 Music

7.2 Sport

7.3 Clothing

7.4 Media

8 Education

8.1 Science and research

9 Health care

10 See also

11 References

12 Bibliography

13 External links

Etymology

The country's place name Sudan is a name given to a geographical region to the south of the Sahara, stretching from Western Africa to eastern Central Africa. The name derives from the Arabic bilād as-sūdān (بلاد السودان), or "the lands of the Blacks".[17] The name is one of several toponyms sharing similar etymologies, ultimately meaning "land of the blacks" or similar meanings, in reference to the dark skin of the inhabitants. Initially, the term "Sudanese" had a negative connotation in the Arabized Sudan due to its association with black African slaves. The idea of "Sudanese" nationalism goes back to the 1930s and 1940s, when it was popularized by young intellectuals.[18]

History

Prehistoric Sudan (before c. 800 BC)

The large mud brick temple, known as the shrek or Western Deffufa, in the ancient city of Kerma

Fortress of the Middle Kingdom, reconstructed under the New Kingdom(about 1200 B.C.)

By the eighth millennium BC, people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mudbrick villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding.[19] During the fifth millennium BC, migrations from the drying Sahara brought neolithic people into the Nile Valley along with agriculture. The population that resulted from this cultural and genetic mixing developed a social hierarchy over the next centuries which became the Kingdom of Kush (with the capital at Kerma) at 1700 BC. Anthropological and archaeological research indicate that during the predynastic period Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were ethnically, and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 BC.[20]

Kingdom of Kush (c. 800 BC–350 AD)

Nubian pyramids in Meroë.

Kušiya soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 480 BCE. Xerxes I tomb relief.

The Kingdom of Kush was an ancient Nubian state centered on the confluences of the Blue Nile and White Nile, and the Atbarah River and the Nile River. It was established after the Bronze Age collapse and the disintegration of the New Kingdom of Egypt, centered at Napata in its early phase.

After King Kashta ("the Kushite") invaded Egypt in the eighth century BC, the Kushite kings ruled as pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt for a century before being defeated and driven out by the Assyrians. At the height of their glory, the Kushites conquered an empire that stretched from what is now known as South Kordofan all the way to the Sinai. Pharaoh Piye attempted to expand the empire into the Near East, but was thwarted by the Assyrian king Sargon II.

The Kingdom of Kush is mentioned in the Bible as having saved the Israelites from the wrath of the Assyrians, although disease among the besiegers was the main reason for the failure to take the city.[21][page needed]

The war that took place between Pharaoh Taharqa and the Assyrian king Sennacherib was a decisive event in western history, with the Nubians being defeated in their attempts to gain a foothold in the Near East by Assyria. Sennacherib's successor Esarhaddon went further, and invaded Egypt itself, deposing Taharqa and driving the Nubians from Egypt entirely. Taharqa fled back to his homeland where he died two years later. Egypt became an Assyrian colony; however, king Tantamani, after succeeding Taharqa, made a final determined attempt to regain Egypt. Esarhaddon died while preparing to leave the Assyrian capital of Nineveh in order to eject him. However, his successor Ashurbanipal (668 – c. 627 BC) sent a large army into southern Egypt and routed Tantamani, ending all hopes of a revival of the Nubian Empire.

During Classical Antiquity, the Nubian capital was at Meroë. In ancient Greek geography, the Meroitic kingdom was known as Ethiopia (a term also used earlier by the Assyrians when encountering the Nubians). The civilization of Kush was among the first in the world to use iron smelting technology. The Nubian kingdom at Meroë persisted until the mid fourth century AD.

Medieval Nubian kingdoms (c. 350–1500)

The three Christian Nubian kingdoms. The northern border of Alodia is unclear, but it also might have been located further north, between the fourth and fifth Nile cataract.[22]

On the turn of the fifth century the Blemmyes established a short-lived state in Upper Egypt and Lower Nubia, probably centered around Talmis (Kalabsha), but before 450 they were already driven out of the Nile Valley by the Nobatians. The latter eventually founded a kingdom on their own, Nobatia.[23]

By the 6th century there were in total three Nubian kingdoms: Nobatia in the north, which had its capital at Pachoras (Faras); the central kingdom, Makuria centred at Tungul (Old Dongola), about 13 kilometres (8 miles) south of modern Dongola; and Alodia, in the heartland of the old Kushitic kingdom, which had its capital at Soba (now a suburb of modern-day Khartoum).[24] Still in the sixth century they converted to Christianity.[25] In the seventh century, probably at some point between 628 and 642, Nobatia was incorporated into Makuria.[26]

Between 639 and 641 the Muslim Arabs of the Rashidun Caliphate conquered Byzantine Egypt. In 641 or 642 and again in 652 they invaded Nubia but were repelled, making the Nubians one of the few who managed to defeat the Arabs during the Islamic expansion. Afterwards the Makurian king and the Arabs agreed on a unique non-aggression pact that also included an annual exchange of gifts, thus acknowledging Makuria's independence.[27] While the Arabs failed to conquer Nubia they began to settle east of the Nile, where they eventually founded several port towns[28] and intermarried with the local Beja.[29]

Moses George, king of Makuria and Alodia

From the mid 8th-mid 11th century the political power and cultural development of Christian Nubia peaked.[30] In 747 Makuria invaded Egypt, which at this time belonged to the declining Umayyads,[31] and it did so again in the early 960s, when it pushed as far north as Akhmim.[32] Makuria maintained close dynastic ties with Alodia, perhaps resulting in the temporary unification of the two kingdoms into one state.[33] The culture of the medieval Nubians has been described as "Afro-Byzantine",[34] but was also increasingly influenced by Arab culture.[35] The state organization was extremely centralized,[36] being based on the Byzantine bureaucracy of the 6th and 7th centuries.[37] Arts flourished in the form of pottery paintings[38] and especially wall paintings.[39] The Nubians developed an own alphabet for their language, Old Nobiin, basing it on the Coptic alphabet, while also utilizing Greek, Coptic and Arabic.[40] Women enjoyed high social status: they had access to education, could own, buy and sell land and often used their wealth to endow churches and church paintings.[41] Even the royal succession was matrilineal, with the son of the king's sister being the rightful heir.[42]

From the late 11th/12th century, Makuria's capital Dongola was in decline, and Alodia's capital declined in the 12th century as well.[43] In the 14th and 15th centuries Bedouin tribes overran most of Sudan,[44] migrating to the Butana, the Gezira, Kordofan and Darfur.[45] In 1365 a civil war forced the Makurian court to flee to Gebel Adda in Lower Nubia, while Dongola was destroyed and left to the Arabs. Afterwards Makuria continued to exist only as a petty kingdom.[46] After the prosperous[47] reign of king Joel (fl. 1463-1484) Makuria probably collapsed.[48]

To the south, the kingdom of Alodia fell to either the Arabs, commanded by tribal leader Abdallah Jamma, or the Funj, an African people originating from the south.[49] Datings range from the 9th century after the Hijra (c. 1396–1494),[50] the late 15th century,[51] 1504[52] to 1509.[53] An alodian rump state might have survived in the form of the kingdom of Fazughli, lasting until 1685.[54]

Islamic kingdoms of Sennar and Darfur (c. 1500–1821)

The great mosque of Sennar, built in the 17th century.[55]

In 1504 the Funj are recorded to have founded the Kingdom of Sennar, in which Abdallah Jamma's realm was incorporated.[56] By 1523, when Jewish traveller David Reubeni visited Sudan, the Funj state already extended as far north as Dongola.[57] Meanwhile, Islam began to be preached on the Nile by Sufi holymen who settled there in the 15th and 16th centuries[58] and by David Reubeni's visit king Amara Dunqas, previously a Pagan or nominal Christian, was recorded to be Muslim.[59] However, the Funj would retain un-Islamic customs like the divine kingship or the consummation of alocohol until the 18th century.[60] Sudanese folk Islam preserved many rituals stemming from Christian traditions until the recent past.[61]

Soon the Funj came in conflict with the Ottomans, who had occupied Suakin around 1526[62] and eventually pushed south along the Nile, reaching the third Nile cataract area in 1583/1584. A subsequent Ottoman attempt to capture Dongola was repelled by the Funj in 1585.[63] Afterwards, Hannik, located just south of the third cataract, would mark the border between the two states.[64] The aftermath of the Ottoman invasion saw the attempted usurpation of Ajib, a minor king of northern Nubia. While the Funj eventually killed him in 1611/1612 his successors, the Abdallab, were granted to govern everything north of the confluence of Blue and White Niles with considerable autonomy.[65]

During the 17th century the Funj state reached its widest extend,[66] but in the following century it began to decline.[67] A coup in 1718 brought a dynastic change,[68] while another one in 1761-1762[69] resulted in the Hamaj regency, where the Hamaj (a people from the Ethiopian borderlands) effectively ruled while the Funj sultans were their mere puppets.[70] Shortly afterwards the sultanate began to fragment;[71] by the early 19th century it was essentially restricted to the Gezira.[72]

Southern Sudan in c. 1800

The coup of 1718 kicked off a policy of pursuing a more orthodox Islam, which in turn promoted the Arabization of the state.[73] In order to legitimize their rule over their Arab subjects the Funj began to propagate an Umayyad descend.[74] North of the confluence of the Blue and White Niles, as far downstream as Al Dabbah, the Nubians adopted the tribal identity of the Arab Jaalin.[75] Until the 19th century Arabic had succeeded in becoming the dominant language of central riverine Sudan[76][77][78] and most of Kordofan.[79]

West of the Nile, in Darfur, the Islamic period saw at first the rise of the Tunjur kingdom, which replaced the old Daju kingdom in the 15th century[80] and extended as far west as Wadai.[81] The Tunjur people were probably Arabized Berbers and, their ruling elite at least, Muslims.[82] In the 17th century the Tunjur were driven from power by the Fur Keira sultanate.[81] The Keira state, nominally Muslim since the reign of Sulayman Solong (r. c. 1660–1680),[83] was initially a small kingdom in northern Jebel Marra,[84] but expanded west- and northwards in the early 18th century[85] and eastwards under the rule of Muhammad Tayrab (r. 1751–1786),[86] peaking in the conquest of Kordofan in 1785.[87] The apogee of this empire, now roughly the size of present-day Nigeria,[87] would last until 1821.[86]

Turkiyah and Mahdist Sudan (1821–1899)

Ismail Pasha, the Ottoman Khedive of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879.

Muhammad Ahmad ruler of Sudan, 1881–1885.

In 1821, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali of Egypt, had invaded and conquered northern Sudan. Although technically the Vali of Egypt under the Ottoman Empire, Muhammad Ali styled himself as Khedive of a virtually independent Egypt. Seeking to add Sudan to his domains, he sent his third son Ismail (not to be confused with Isma'il Pasha mentioned later) to conquer the country, and subsequently incorporate it into Egypt. Except of the Shaiqiya and the Darfur sultanate in Kordofan he was met without resistance. The Egyptian policy of conquest was expanded and intensified by Ibrahim Pasha's son, Isma'il, under whose reign most of the remainder of modern-day Sudan was conquered.

The Egyptian authorities made significant improvements to the Sudanese infrastructure (mainly in the north), especially with regard to irrigation and cotton production. In 1879, the Great Powers forced the removal of Ismail and established his son Tewfik Pasha in his place. Tewfik's corruption and mismanagement resulted in the 'Urabi revolt, which threatened the Khedive's survival. Tewfik appealed for help to the British, who subsequently occupied Egypt in 1882. Sudan was left in the hands of the Khedivial government, and the mismanagement and corruption of its officials.[88][89]

During the Khedivial period, dissent had spread due to harsh taxes imposed on most activities. Taxation on irrigation wells and farming lands were so high most farmers abandoned their farms and livestock. During the 1870s, European initiatives against the slave trade had an adverse impact on the economy of northern Sudan, precipitating the rise of Mahdist forces.[90]Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abd Allah, the Mahdi (Guided One), offered to the ansars (his followers) and those who surrendered to him a choice between adopting Islam or being killed. The Mahdiyah (Mahdist regime) imposed traditional Sharia Islamic laws.

From his announcement of the Mahdiyya in June 1881 until the fall of Khartoum in January 1885, Muhammad Ahmad led a successful military campaign against the Turco-Egyptian government of the Sudan, known as the Turkiyah. Muhammad Ahmad died on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of Khartoum. After a power struggle amongst his deputies, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, with the help primarily of the Baggara of western Sudan, overcame the opposition of the others and emerged as unchallenged leader of the Mahdiyah. After consolidating his power, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad assumed the title of Khalifa (successor) of the Mahdi, instituted an administration, and appointed Ansar (who were usually Baqqara) as emirs over each of the several provinces.

The flight of the Khalifa after his defeat at the Battle of Omdurman.

Regional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's brutal methods to extend his rule throughout the country. In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrating as far as Gondar. In March 1889, king Yohannes IV of Ethiopia marched on Metemma; however, after Yohannes fell in battle, the Ethiopian forces withdrew. Abd ar Rahman an Nujumi, the Khalifa's general, attempted an invasion of Egypt in 1889, but British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. The failure of the Egyptian invasion broke the spell of the Ansar's invincibility. The Belgians prevented the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria, and in 1893, the Italians repelled an Ansar attack at Agordat (in Eritrea) and forced the Ansar to withdraw from Ethiopia.

In the 1890s, the British sought to re-establish their control over Sudan, once more officially in the name of the Egyptian Khedive, but in actuality treating the country as a British colony. By the early 1890s, British, French and Belgian claims had converged at the Nile headwaters. Britain feared that the other powers would take advantage of Sudan's instability to acquire territory previously annexed to Egypt. Apart from these political considerations, Britain wanted to establish control over the Nile to safeguard a planned irrigation dam at Aswan. Herbert Kitchener led military campaigns against the Mahdist Sudan from 1896 to 1898. Kitchener's campaigns culminated in a decisive victory in the Battle of Omdurman on 2 September 1898.

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (1899–1956)

The Mahdist War was fought between a group of Muslim dervishes, called Mahdists, who had over-run much of Sudan, and the British forces.

In 1899, Britain and Egypt reached an agreement under which Sudan was run by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent. In reality Sudan was effectively administered as a Crown colony. The British were keen to reverse the process, started under Muhammad Ali Pasha, of uniting the Nile Valley under Egyptian leadership, and sought to frustrate all efforts aimed at further uniting the two countries.

Under the Delimitation, Sudan's border with Abyssinia was contested by raiding tribesmen trading slaves, breaching boundaries of law. In 1905 Local chieftain Sultan Yambio reluctant to the end gave up the struggle with British forces that had occupied the Kordofan region, finally ending the lawlessness. The continued British administration of Sudan fuelled an increasingly strident nationalist backlash, with Egyptian nationalist leaders determined to force Britain to recognise a single independent union of Egypt and Sudan. With a formal end to Ottoman rule in 1914, Sir Reginald Wingate was sent that December to occupy Sudan as the new Military Governor. Hussein Kamel was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, as was his brother and successor, Fuad I. They continued upon their insistence of a single Egyptian-Sudanese state even when the Sultanate of Egypt was retitled as the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan, but it was Saad Zaghloul who continued to be frustrated in the ambitions until his death in 1927.[91]

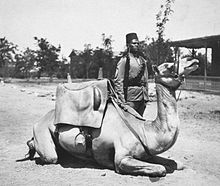

A camel soldier of the native forces of the British army, early 20th century.

From 1924 until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate territories, the north and south. The assassination of a Governor-General of Khartoum in Cairo was the causative factor; it brought demands of the newly elected Wafd government from colonial forces. A permanent establishment of two battalions in Khartoum was renamed the Sudan Defence Force acting as under the government, replacing the former garrison of Egyptian army soldiers, saw action afterwards during the Wal Wal Incident.[92] The Wafdist parliamentary majority had rejected Sarwat Pasha's accommodation plan with Austen Chamberlain in London; yet Cairo still needed the money. The Sudan Government's revenue had reached a peak in 1928 at £6.6 million, thereafter the Wafdist disruptions, and Italian borders incursions from Somaliland, London decided to reduce expenditure during the Great Depression. Cotton and Gum exports were dwarfed by the necessity to import almost everything from Britain leading to a balance of payments deficit at Khartoum.[93]

In July 1936 the Liberal Constitutional leader, Muhammed Mahmoud was persuaded to bring Wafd delegates to London to sign the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, "the beginning of a new stage in Anglo-Egyptian relations", wrote Anthony Eden.[94] The British Army was allowed to return to the Sudan to protect the Canal Zone. They were able to find training facilities; and the RAF was free to fly over Egyptian territory. It did not however resolve the problem of Sudan: the Sudanese Intelligentsia agitated for a return to metropolitan rule, conspiring with Germany's agents.[95]

Mussolini made it clear that he could not invade Abyssinia without first conquering Egypt and the Sudan; they intended unification of Libya with Italian East Africa. The British Imperial General Staff prepared for a military defence of the region, which was lamentably thin on the ground.[96] The British ambassador blocked Italian attempts to secure a Non-Aggression Treaty with Egypt-Sudan. But Mahmoud was a supporter of the Mufti of Jerusalem; the region was caught between the Empire's efforts to save the Jews, and moderate Arab calls to halt migration.[97]

The Sudanese Government was directly involved militarily in the East African Campaign. Formed in 1925, the Sudan Defence Force played an active part in responding to incursions early in World War Two. Italian troops occupied Kassala and other border areas from Italian Somaliland during 1940. In 1942, the SDF also played a part in the invasion of the Italian colony by British and Commonwealth forces. The last British governor-general was Robert George Howe.

The Egyptian revolution of 1952 finally heralded the beginning of the march towards Sudanese independence. Having abolished the monarchy in 1953, Egypt's new leaders, Mohammed Naguib, whose mother was Sudanese, and later Gamal Abdel Nasser, believed the only way to end British domination in Sudan was for Egypt to officially abandon its claims of sovereignty. In addition Nasser knew it would be difficult for Egypt to govern an impoverished Sudan after its independence. The British on the other hand continued their political and financial support for the Mahdist successor, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, whom it was believed would resist Egyptian pressure for Sudanese independence. Rahman was capable of this, but his regime was plagued by political ineptitude, which garnered a colossal loss of support in northern and central Sudan. Both Egypt and Britain sensed a great instability fomenting, and thus opted to allow both Sudanese regions, north and south to have a free vote on whether they wished independence or a British withdrawal.

Independence (1956–present)

Sudan's flag raised at independence ceremony on 1 January 1956 by the Prime Minister Ismail al-Azhari and in presence of opposition leader Mohamed Ahmed Almahjoub

A polling process was carried out resulting in composition of a democratic parliament and Ismail al-Azhari was elected first Prime Minister and led the first modern Sudanese government.[98] On 1 January 1956, in a special ceremony held at the People's Palace, the Egyptian and British flags were lowered and the new Sudanese flag, composed of green, blue and yellow stripes, was raised in their place by the prime minister Ismail al-Azhari.

Dissatisfaction culminated in a second coup d'état on 25 May 1969. The coup leader, Col. Gaafar Nimeiry, became prime minister, and the new regime abolished parliament and outlawed all political parties. Disputes between Marxist and non-Marxist elements within the ruling military coalition resulted in a briefly successful coup in July 1971, led by the Sudanese Communist Party. Several days later, anti-communist military elements restored Nimeiry to power.

In 1972, the Addis Ababa Agreement led to a cessation of the north-south civil war and a degree of self-rule. This led to ten years hiatus in the civil war but less happily an end to American investment in the Jonglei Canal project. This had been considered absolutely essential to irrigate the Upper Nile region and to prevent an environmental catastrophe and wide-scale famine among the local tribes, most especially the Dinka. In the civil war that followed their homeland was raided looted, pillaged and burned. Many of the tribe were murdered in a bloody civil war that raged for over 20 years.

1971 Sudanese coup d'état

Until the early 1970s, Sudan's agricultural output was mostly dedicated to internal consumption. In 1972, the Sudanese government became more pro-Western, and made plans to export food and cash crops. However, commodity prices declined throughout the 1970s causing economic problems for Sudan. At the same time, debt servicing costs, from the money spent mechanizing agriculture, rose. In 1978, the IMF negotiated a Structural Adjustment Program with the government. This further promoted the mechanized export agriculture sector. This caused great hardship for the pastoralists of Sudan (see Nuba peoples). In 1976, the Ansars had mounted a bloody but unsuccessful coup attempt. But in July 1977, President Nimeiry met with Ansar leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, opening the way for a possible reconciliation. Hundreds of political prisoners were released, and in August a general amnesty was announced for all oppositionists.

On 30 June 1989, Colonel Omar al-Bashir led a bloodless military coup.[99] The new military government suspended political parties and introduced an Islamic legal code on the national level.[100] Later al-Bashir carried out purges and executions in the upper ranks of the army, the banning of associations, political parties, and independent newspapers, and the imprisonment of leading political figures and journalists.[101] On 16 October 1993, al-Bashir appointed himself "President" and disbanded the Revolutionary Command Council. The executive and legislative powers of the council were taken by al-Bashir.[102]

1990s–2000s

In the 1996 general election he was the only candidate by law to run for election.[103] Sudan became a one-party state under the National Congress Party (NCP).[104] During the 1990s, Hassan al-Turabi, then Speaker of the National Assembly, reached out to Islamic fundamentalist groups, invited Osama bin Laden to the country.[105] The United States subsequently listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism.[106] The U.S. bombed Sudan in 1998, targeting the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory. Al-Turabi's influence began to wane, others in favour of more pragmatic leadership tried to change Sudan's international isolation.[107] The country worked to appease its critics by expelling members of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and encouraging bin Laden to leave.[108]

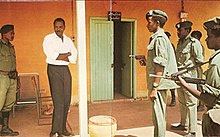

Government Militia in Darfur

Before the 2000 presidential election, al-Turabi introduced a bill to reduce the President's powers, prompting al-Bashir to order a dissolution and declare a state of emergency. When al-Turabi urged a boycott of the President's re-election campaign signing agreement with Sudan People's Liberation Army, al-Bashir suspected they were plotting to overthrow the government.[109] Hassan al-Turabi was jailed later the same year.[110]

In February 2003, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) groups in Darfur took up arms, accusing the Sudanese government of oppressing non-Arab Sudanese in favor of Sudanese Arabs, precipitating the War in Darfur. The conflict has since been described as a genocide,[111] and the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague has issued two arrest warrants for al-Bashir.[112][113] Arabic-speaking nomadic militias known as the Janjaweed stand accused of many atrocities.

On 9 January 2005, the government signed the Nairobi Comprehensive Peace Agreement with the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) with the objective of ending the Second Sudanese Civil War. The United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) was established under the UN Security Council Resolution 1590 to support its implementation. The peace agreement was a prerequisite to the 2011 referendum: the result was a unanimous vote in favour of secession of South Sudan; the region of Abyei will hold its own referendum at a future date.

South Sudanese independence referendum, 2011

The Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) was the primary member of the Eastern Front, a coalition of rebel groups operating in eastern Sudan. After the peace agreement, their place was taken in February 2004 after the merger of the larger Hausa and Beja Congress with the smaller Rashaida Free Lions.[114] A peace agreement between the Sudanese government and the Eastern Front was signed on 14 October 2006, in Asmara. On 5 May 2006, the Darfur Peace Agreement was signed, aiming at ending the three-year-long conflict.[115] The Chad–Sudan Conflict (2005–2007) had erupted after the Battle of Adré triggered a declaration of war by Chad.[116] The leaders of Sudan and Chad signed an agreement in Saudi Arabia on 3 May 2007 to stop fighting from the Darfur conflict spilling along their countries' 1,000-kilometre (600 mi) border.[117]

In July 2007 the country was hit by devastating floods,[118] with over 400,000 people being directly affected.[119] Since 2009, a series of ongoing conflicts between rival nomadic tribes in Sudan and South Sudan have caused a large number of civilian casualties.

Partition and rehabilitation

The Sudanese conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile in the early 2010s between the Army of Sudan and the Sudan Revolutionary Front started as a dispute over the oil-rich region of Abyei in the months leading up to South Sudanese independence, though it is also related to civil war in Darfur that is nominally resolved.

On January 13, 2017, the president of the US, Barack Obama, signed an Executive Order that lifted many sanctions placed against Sudan and assets of its government held abroad. On October 6, 2017, the following president of the US, Donald Trump, lifted most of the remaining sanctions against the country and its petroleum, export-import, and property industries.[120]

Geography

A map of Sudan. The Hala'ib Triangle has been under Egyptian administration since 2000.

A Köppen climate classification map of Sudan.

Sudan is situated in northern Africa, with a 853 km (530 mi) coastline bordering the Red Sea.[121] It has land borders with Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Chad, and Libya. With an area of 1,886,068 km2 (728,215 sq mi), it is the third-largest country on the continent (after Algeria and Democratic Republic of the Congo) and the sixteenth-largest in the world.

Sudan lies between latitudes 8° and 23°N. The terrain is generally flat plains, broken by several mountain ranges. In the west the Deriba Caldera (3,042 m or 9,980 ft), located in the Marrah Mountains, is the highest point in Sudan. In the east are the Red Sea Hills.[122]

The Blue and White Nile rivers meet in Khartoum to form the Nile, which flows northwards through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. The Blue Nile's course through Sudan is nearly 800 km (497 mi) long and is joined by the Dinder and Rahad Rivers between Sennar and Khartoum. The White Nile within Sudan has no significant tributaries.

There are several dams on the Blue and White Niles. Among them are the Sennar and Roseires Dams on the Blue Nile, and the Jebel Aulia Dam on the White Nile. There is also Lake Nubia on the Sudanese-Egyptian border.

Rich mineral resources are available in Sudan including asbestos, chromite, cobalt, copper, gold, granite, gypsum, iron, kaolin, lead, manganese, mica, natural gas, nickel, petroleum, silver, tin, uranium and zinc.[123]

Climate

The amount of rainfall increases towards the south. The central and the northern part have extremely dry desert areas such as the Nubian Desert to the northeast and the Bayuda Desert to the east; in the south there are swamps and rainforest. Sudan's rainy season lasts for about three months (July to September) in the north, and up to six months (June to November) in the south.

The dry regions are plagued by sandstorms, known as haboob, which can completely block out the sun. In the northern and western semi-desert areas, people rely on the scant rainfall for basic agriculture and many are nomadic, travelling with their herds of sheep and camels. Nearer the River Nile, there are well-irrigated farms growing cash crops.[124] The sunshine duration is very high all over the country but especially in deserts where it could soar to over 4,000 h per year.

Environmental issues

Desertification is a serious problem in Sudan.[125] There is also concern over soil erosion. Agricultural expansion, both public and private, has proceeded without conservation measures. The consequences have manifested themselves in the form of deforestation, soil desiccation, and the lowering of soil fertility and the water table.[126]

The nation's wildlife is threatened by poaching. As of 2001, twenty-one mammal species and nine bird species are endangered, as well as two species of plants. Critically endangered species include: the waldrapp, northern white rhinoceros, tora hartebeest, slender-horned gazelle, and hawksbill turtle. The Sahara oryx has become extinct in the wild.[127]

Government and politics

Officially, the politics of Sudan takes place in the framework of a federal presidential representative democratic republic, where the President of Sudan is head of state, head of government and commander-in-chief of the Sudan People's Armed Forces in a multi-party system. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the bicameral parliament—the National Legislature, with its National Assembly (lower chamber) and the Council of States (upper chamber). The judiciary is independent and obtained by the Constitutional Court.[11] It is part of the Northern Africa grouping of the UN geoscheme.[128]

JEM rebels in Darfur. Both the government and the rebels have been accused of atrocities.

Executive posts are divided between the NCP, the SPLA, the Sudanese Eastern Front and factions of the Umma Party and Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

The military situation in Sudan as of 21 February 2016.

Under control of the Sudanese Government and Allies

Under control of the Sudan Revolutionary Front and allies

Under control of the Sudanese Awakening Revolutionary Council

According to the new 2005 constitution, the bicameral National Legislature is the official Sudanese parliament and is divided between two chambers—the National Assembly, a lower house with 450 seats, and the Council of States, an upper house with 50 seats. Thus the parliament consists of 500 appointed members altogether, where all are indirectly elected by state legislatures to serve six-year terms.[11]

Despite his international arrest warrant, al-Bashir was a candidate in the 2010 Sudanese presidential election, the first democratic election with multiple political parties participating in twenty-four years.[129] In the build-up to the vote, Sudanese pro-democracy activists say they faced intimidation by the government[130] and the International Crisis Group reported that the ruling party had gerrymandered electoral districts.[131] A few days before the vote, the main opposition candidate, Yasir Arman from the SPLM, withdrew from the race.[132] The U.S.-based Carter Center, which helped monitor the elections, described the vote tabulation process as "highly chaotic, non-transparent and vulnerable to electoral manipulation."[133] Al-Bashir was declared the winner of the election with sixty-eight percent of the vote.[129]

Sharia law

The legal system in Sudan is based on Islamic Sharia law. The 2005 Naivasha Agreement, ending the civil war between north and south Sudan, established some protections for non-Muslims in Khartoum. Sudan's application of Sharia law is geographically inconsistent.[134]

Stoning remains a judicial punishment in Sudan. Between 2009 and 2012, several women were sentenced to death by stoning.[135][136][137]Flogging is a legal punishment. Between 2009 and 2014, many people were sentenced to 40–100 lashes.[138][139][140][141][142][143] In August 2014, several Sudanese men died in custody after being flogged.[144][145][146] 53 Christians were flogged in 2001.[147] Sudan's public order law allows police officers to publicly whip women who are accused of public indecency.[148]

Crucifixion is a legal punishment. In 2002, 88 people were sentenced to death for crimes relating to murder, armed robbery, and participating in ethnic clashes, Amnesty International wrote that they could be executed by either hanging or crucifixion.[149]

International Court of Justice jurisdiction is accepted, though with reservations. Under the terms of the Naivasha Agreement, Islamic law did not apply in South Sudan.[150] Since the secession of South Sudan there is some uncertainty as to whether Sharia law will now apply to the non-Muslim minorities present in Sudan, especially because of contradictory statements by al-Bashir on the matter.[151]

The judicial branch of the Sudanese government consists of a Constitutional Court of nine justices, the National Supreme Court, the Court of Cassation,[152] and other national courts; the National Judicial Service Commission provides overall management for the judiciary.

Foreign relations

Bashir (right) and U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick, 2005

Sudan has had a troubled relationship with many of its neighbours and much of the international community, owing to what is viewed as its radical Islamic stance. For much of the 1990s, Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia formed an ad-hoc alliance called the "Front Line States" with support from the United States to check the influence of the National Islamic Front government. The Sudanese Government supported anti-Ugandan rebel groups such as the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA).[153]

As the National Islamic Front regime in Khartoum gradually emerged as a real threat to the region and the world, the U.S. began to list Sudan on its list of State Sponsors of Terrorism. After the US listed Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism, the NIF decided to develop relations with Iraq, and later Iran, the two most controversial countries in the region.

From the mid-1990s, Sudan gradually began to moderate its positions as a result of increased U.S. pressure following the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, in Tanzania and Kenya, and the new development of oil fields previously in rebel hands. Sudan also has a territorial dispute with Egypt over the Hala'ib Triangle. Since 2003, the foreign relations of Sudan had centered on the support for ending the Second Sudanese Civil War and condemnation of government support for militias in the war in Darfur.

Sudan has extensive economic relations with China. China obtains ten percent of its oil from Sudan. According to a former Sudanese government minister, China is Sudan's largest supplier of arms.[154]

In December 2005, Sudan became one of the few states to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.[155]

In 2015, Sudan participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh,[156] who was deposed in the 2011 uprising.[157]

Armed Forces

The Sudan People's Armed Forces is the regular forces of Sudan and is divided into five branches: the Sudanese Army, Sudanese Navy (including the Marine Corps), Sudanese Air Force, Border Patrol and the Internal Affairs Defense Force, totalling about 200,000 troops. The military of Sudan has become a well-equipped fighting force, thanks to increasing local production of heavy and advanced arms. These forces are under the command of the National Assembly and its strategic principles include defending Sudan's external borders and preserving internal security.

Since the Darfur crisis in 2004, safe-keeping the central government from the armed resistance and rebellion of paramilitary rebel groups such as the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), the Sudanese Liberation Army (SLA) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) have been important priorities. While not official, the Sudanese military also uses nomad militias, the most prominent being the Janjaweed, in executing a counter-insurgency war.[158] Somewhere between 200,000[159] and 400,000[11][160][161] people have died in the violent struggles.

International organizations in Sudan

Several UN agents are operating in Sudan such as the World Food Program (WFP); the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); the United Nations Industrial Development Organizations (UNIDO); the United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF); the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); the United Nations Mine Service (UNMAS), the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the World Bank. Also present is the International Organization for Migration (IOM).[162][163]

Since Sudan has experienced civil war for many years, many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are also involved in humanitarian efforts to help internally displaced people. The NGOs are working in every corner of Sudan, especially in the southern part and western parts. During the civil war, international nongovernmental organizations such as the Red Cross were operating mostly in the south but based in the capital Khartoum.[164] The attention of NGOs shifted shortly after the war broke out in the western part of Sudan known as Darfur. The most visible organization in South Sudan is the Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) consortium.[165] Some international trade organizations categorize Sudan as part of the Greater Horn of Africa[166]

Even though most of the international organizations are substantially concentrated in both South Sudan and Darfur region, some of them are working in the northern part as well. For example, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization is successfully operating in Khartoum, the capital. It is mainly funded by the European Union and recently opened more vocational training. The Canadian International Development Agency is operating largely in northern Sudan.[167]

Human rights

Since 1983, a combination of civil war and famine has taken the lives of nearly 2 million people in Sudan.[168] It is estimated that as many as 200,000 people had been taken into slavery during the Second Sudanese Civil War.[169]

Sudan ranks 172 of 180 countries in terms of freedom of the press according to Reporters Without Borders, yet more curbs of press freedom to report official corruption are planned.[170]

Muslims who convert to Christianity can face the death penalty for apostasy, see Persecution of Christians in Sudan and the death sentence against Mariam Yahia Ibrahim Ishag (who actually was raised as Christian). According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 88% of women in Sudan had undergone female genital mutilation.[171] Sudan's Personal Status law on marriage has been criticized for restricting women's rights and allowing child marriage.[172][173] Evidence suggests that support for female genital mutilation remains high, especially among rural and less well educated groups, although it has been declining in recent years.[174]Homosexuality is illegal and is a capital offense in Sudan.[175]

Darfur

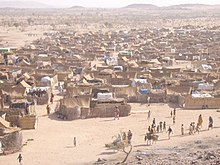

Darfur refugee camp in Chad, 2005

A letter dated 14 August 2006, from the executive director of Human Rights Watch found that the Sudanese government is both incapable of protecting its own citizens in Darfur and unwilling to do so, and that its militias are guilty of crimes against humanity. The letter added that these human-rights abuses have existed since 2004.[176] Some reports attribute part of the violations to the rebels as well as the government and the Janjaweed. The U.S. State Department's human-rights report issued in March 2007 claims that "[a]ll parties to the conflagration committed serious abuses, including widespread killing of civilians, rape as a tool of war, systematic torture, robbery and recruitment of child soldiers."[177]

Over 2.8 million civilians have been displaced and the death toll is estimated at 300,000 killed.[178] Both government forces and militias allied with the government are known to attack not only civilians in Darfur, but also humanitarian workers. Sympathizers of rebel groups are arbitrarily detained, as are foreign journalists, human-rights defenders, student activists and displaced people in and around Khartoum, some of whom face torture. The rebel groups have also been accused in a report issued by the U.S. government of attacking humanitarian workers and of killing innocent civilians.[179] According to UNICEF, in 2008, there were as many as 6,000 child soldiers in Darfur.[180]

Disputed areas and zones of conflict

- In mid-April 2012, the South Sudanese army captured the Heglig oil field from Sudan.

- In mid-April 2012 the Sudanese army recaptured Heglig.

Kafia Kingi and Radom National Park was a part of Bahr el Ghazal in 1956.[181] Sudan has recognized South Sudan independence according to the borders for 1 January 1956.[182]

- The Abyei Area is disputed region between Sudan and South Sudan. It is currently under Sudan rule.

- The states of South Kurdufan and Blue Nile are to hold "popular consultations" to determine their constitutional future within the Sudan.

- The Hala'ib Triangle is disputed region between Sudan and Egypt. It is currently under Egyptian administration.

Bir Tawil is a terra nullius occurring on the border between Egypt and Sudan, claimed by neither state.

Administrative divisions

Sudan is divided into 18 states (wilayat, sing. wilayah). They are further divided into 133 districts.

Central and northern states

Darfur

Eastern Front

Abyei Area

South Kurdufan and Blue Nile states

.mw-parser-output div.columns-2 div.column{float:left;width:50%;min-width:300px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-3 div.column{float:left;width:33.3%;min-width:200px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-4 div.column{float:left;width:25%;min-width:150px}.mw-parser-output div.columns-5 div.column{float:left;width:20%;min-width:120px}

|

|

|

Regional bodies and areas of conflict

In addition to the states, there also exist regional administrative bodies established by peace agreements between the central government and rebel groups.

- The Darfur Regional Authority was established by the Darfur Peace Agreement to act as a co-ordinating body for the states that make up the region of Darfur.

- The Eastern Sudan States Coordinating Council was established by the Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement between the Sudanese Government and the rebel Eastern Front to act as a coordinating body for the three eastern states.

- The Abyei Area, located on the border between South Sudan and the Republic of the Sudan, currently has a special administrative status and is governed by an Abyei Area Administration. It was due to hold a referendum in 2011 on whether to join an independent South Sudan or remain part of the Republic of the Sudan.

Economy

Oil and gas concessions in Sudan – 2004

In 2010, Sudan was considered the 17th-fastest-growing economy[183] in the world and the rapid development of the country largely from oil profits even when facing international sanctions was noted by The New York Times in a 2006 article.[184] Because of the secession of South Sudan, which contained over 80 percent of Sudan's oilfields, Sudan entered a phase of stagflation, GDP growth slowed to 3.4 percent in 2014, 3.1 percent in 2015 and is projected to recover slowly to 3.7 percent in 2016 while inflation remained as high as 21.8% as of 2015[update].[185]

Even with the oil profits before the secession of South Sudan, Sudan still faced formidable economic problems, and its growth was still a rise from a very low level of per capita output. The economy of Sudan has been steadily growing over the 2000s, and according to a World Bank report the overall growth in GDP in 2010 was 5.2 percent compared to 2009 growth of 4.2 percent.[11] This growth was sustained even during the war in Darfur and period of southern autonomy preceding South Sudan's independence.[186][187]Oil was Sudan's main export, with production increasing dramatically during the late 2000s, in the years before South Sudan gained independence in July 2011. With rising oil revenues, the Sudanese economy was booming, with a growth rate of about nine percent in 2007. The independence of oil-rich South Sudan, however, placed most major oilfields out of the Sudanese government's direct control and oil production in Sudan fell from around 450,000 barrels per day (72,000 m3/d) to under 60,000 barrels per day (9,500 m3/d). Production has since recovered to hover around 250,000 barrels per day (40,000 m3/d) for 2014–15.

In order to export oil, South Sudan relies on a pipeline to Port Sudan on Sudan's Red Sea coast, as South Sudan is a landlocked country, as well as the oil refining facilities in Sudan. In August 2012, Sudan and South Sudan agreed a deal to transport South Sudanese oil through Sudanese pipelines to Port Sudan.[188]

The People's Republic of China is one of Sudan's major trading partners, China owns a 40 percent share in the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company.[189] The country also sells Sudan small arms, which have been used in military operations such as the conflicts in Darfur and South Kordofan.[190]

While historically agriculture remains the main source of income and employment hiring of over 80 percent of Sudanese, and makes up a third of the economic sector, oil production drove most of Sudan's post-2000 growth. Currently, the International Monetary Fund IMF is working hand in hand with Khartoum government to implement sound macroeconomic policies. This follows a turbulent period in the 1980s when debt-ridden Sudan's relations with the IMF and World Bank soured, culminating in its eventual suspension from the IMF.[191][page needed] The program has been in place since the early 1990s, and also work-out exchange rate and reserve of foreign exchange.[11] Since 1997, Sudan has been implementing the macroeconomic reforms recommended by the International Monetary Fund.[citation needed]

Agricultural production remains Sudan's most-important sector, employing 80 percent of the workforce and contributing 39 percent of GDP, but most farms remain rain-fed and susceptible to drought. Instability, adverse weather and weak world-agricultural prices ensures that much of the population will remain at or below the poverty line for years.

The Merowe Dam, also known as Merowe Multi-Purpose Hydro Project or Hamdab Dam, is a large construction project in Northern Sudan, about 350 kilometres (220 mi) north of the capital, Khartoum. It is situated on the River Nile, close to the Fourth Cataract where the river divides into multiple smaller branches with large islands in between. Merowe is a city about 40 kilometres (25 mi) downstream from the dam's construction site.

The main purpose of the dam will be the generation of electricity. Its dimensions make it the largest contemporary hydropower project in Africa. The construction of the dam was finished December 2008, supplying more than 90 percent of the population with electricity. Other gas-powered generating stations are operational in Khartoum State and other States.

According to the Corruptions Perception Index, Sudan is one of the most corrupt nations in the world.[192] According to the Global Hunger Index of 2013, Sudan has an GHI indicator value of 27.0 indicating that the nation has an 'Alarming Hunger Situation' and earning the nation the distinction of being the 5th hungriest nation in the world.[193] According to the 2015 Human Development Index (HDI) Sudan ranked the 167th place in Human Development, indicating Sudan still has one of the lowest human development in the world.[194] Almost one-fifth of Sudan's population lives below the international poverty line which means living on less than US$1.25 per day.[195]

Demographics

Student from Khartoum

| Population in Sudan[4] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 5.7 | ||

| 2000 | 27.2 | ||

| 2016 | 39.6 | ||

In Sudan's 2008 census, the population of Northern, Western and Eastern Sudan was recorded to be over 30 million.[196] This puts present estimates of the population of Sudan after the secession of South Sudan at a little over 30 million people. This is a significant increase over the past two decades as the 1983 census put the total population of Sudan, including present-day South Sudan, at 21.6 million.[197] The population of Greater Khartoum (including Khartoum, Omdurman, and Khartoum North) is growing rapidly and was recorded to be 5.2 million.

Despite being a refugee-generating country, Sudan also hosts a refugee population. According to the World Refugee Survey 2008, published by the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, 310,500 refugees and asylum seekers lived in Sudan in 2007. The majority of this population came from Eritrea (240,400 people), Chad (45,000), Ethiopia (49,300) and the Central African Republic (2,500).[198] The Sudanese government UN High Commissioner for Refugees in 2007 forcibly deported at least 1,500 refugees and asylum seekers during the year. Sudan is a party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.[198]

Ethnic groups

Sudanese Arab of Al-Manasir

The Arab presence is estimated at 70% of the Sudanese population.[11] Others include the Arabized ethnic groups of Nubians, Zaghawa, and Copts.[199][200]

Sudan has 597 groups that speak over 400 different languages and dialects.[201]Sudanese Arabs are by far the largest ethnic group in Sudan. They are almost entirely Muslims; while the majority speak Sudanese Arabic, some other Arab tribes speak different Arabic dialects like Awadia and Fadnia tribes and Bani Arak tribes who speak Najdi Arabic; and Rufa'a, Beni Ḥassān, Al-Ashraf, Kinanah and Rashaida who speak Hejazi Arabic. In addition, the Western province comprises various ethnic groups, while a few Arab Bedouin of the northern Rizeigat and others who speak Sudanese Arabic share the same culture and backgrounds of the Sudanese Arabs.

The majority of Arabized and indigenous tribes like the Fur, Zaghawa, Borgo, Masalit and some Baggara ethnic groups, who speak Chadian Arabic, show less cultural integration because of cultural, linguistic and genealogical variations with other Arab and Arabized tribes.[202]

Sudanese Arabs of Northern and Eastern parts descend primarily from migrants from the Arabian Peninsula and intermarriages with the pre-existing indigenous populations of Sudan, especially the Nubian people, who also share a common history with Egypt. Additionally, a few pre-Islamic Arabian tribes existed in Sudan from earlier migrations into the region from Western Arabia, although most Arabs in Sudan are dated from migrations after the 12th century.[203]

The vast majority of Arab tribes in Sudan migrated into the Sudan in the 12th century, intermarried with the indigenous Nubian and other African populations and introduced Islam.[204]

Sudan consists of numerous other non-Arabic groups, such as the Masalit, Zaghawa, Fulani, Northern Nubians, Nuba, and the Beja people.

There is also a small, but prominent Greek community.

Languages

The Arabic-speaking Rashaida came to Sudan from Arabia about 170 years ago.

Approximately 70 languages are native to Sudan.[205]

Sudanese Arabic is the most widely spoken language in the country. It is the variety of Arabic, an Afroasiatic language of the Semitic branch spoken throughout Sudan. The dialect has borrowed much vocabulary from local Nilo-Saharan languages (Nobiin, Fur, Zaghawa, Mabang). This has resulted in a variety of Arabic that is unique to Sudan, reflecting the way in which the country has been influenced by Nilotic, Arab, and western cultures. Few nomads in Sudan still have similar accents to the ones in Saudi Arabia. Other important languages include Beja (Bedawi) along the Red Sea, with perhaps 2 million speakers. It is the only language from the Afroasiatic family's Cushitic branch that is today spoken in the territory.

As with South Sudan, a number of Nilo-Saharan languages are also spoken in Sudan. Fur speakers inhabit the west (Darfur), with perhaps a million speakers. There are likewise various Nubian languages, with over 6 million speakers along the Nile in the north. The most linguistically diverse region in the country is the Nuba Hills area in Kordofan, inhabited by speakers of multiple language families, with Darfur and other border regions being second.

The Niger–Congo family is represented by many of the Kordofanian languages, and Indo-European by Domari (Gypsy) and English. Historically, Old Nubian, Greek, and Coptic were the languages of Christian Nubia, while Meroitic was the language of the Kingdom of Kush, which conquered Egypt.

Sudan also has multiple regional sign languages, which are not mutually intelligible. A 2009 proposal for a unified Sudanese Sign Language had been worked out, but was not widely known.[206]

Prior to 2005, Arabic was the nation's sole official language.[207] In the 2005 constitution, Sudan's official languages became Arabic and English.[1]

Urban areas

Largest cities or towns in Sudan According to the 2008 census | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||||||

Omdurman  Khartoum | 1 | Omdurman | Khartoum | 1,849,659 |  Khartoum North | ||||

| 2 | Khartoum | Khartoum | 1,410,858 | ||||||

| 3 | Khartoum North | Khartoum | 1,012,211 | ||||||

| 4 | Nyala | South Darfur | 492,984 | ||||||

| 5 | Port Sudan | Red Sea | 394,561 | ||||||

| 6 | El-Obeid | North Kordofan | 345,126 | ||||||

| 7 | Kassala | Kassala | 298,529 | ||||||

| 8 | Madani | Gezira | 289,482 | ||||||

| 9 | El-Gadarif | Al Qadarif | 269,395 | ||||||

| 10 | Al-Fashir | North Darfur | 217,827 | ||||||

Religion

Masjid Al-Nilin, August 2007

At the 2011 division which split off South Sudan, over 97% of the population in the remaining Sudan adheres to Islam.[209] Most Muslims are divided between two groups: Sufi and Salafi (Ansar Al Sunnah) Muslims. Two popular divisions of Sufism, the Ansar and the Khatmia, are associated with the opposition Umma and Democratic Unionist parties, respectively. Only the Darfur region has traditionally been bereft of the Sufi brotherhoods common in the rest of the country.[210]

Significant, long-established groups of Coptic Orthodox and Greek Orthodox Christians exist in Khartoum and other northern cities. Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox communities also exist in Khartoum and eastern Sudan, largely made up of refugees and migrants from the past few decades. The largest groups affiliated with Western Christian denominations are Roman Catholic and Anglican. Other Christian groups with smaller followings in the country include the Africa Inland Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Sudan Church of Christ, the Sudan Interior Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, the Sudan Pentecostal Church, the Sudan Evangelical Presbyterian Church (in the North).

Religious identity plays a role in the country's political divisions. Northern and western Muslims have dominated the country's political and economic system since independence. The NCP draws much of its support from Islamists, Salafis/Wahhabis and other conservative Arab Muslims in the north. The Umma Party has traditionally attracted Arab followers of the Ansar sect of Sufism as well as non-Arab Muslims from Darfur and Kordofan. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) includes both Arab and non-Arab Muslims in the north and east, especially those in the Khatmia Sufi sect.

Culture

Sudanese culture melds the behaviors, practices, and beliefs of about 578 ethnic groups, communicating in 145 different languages, in a region microcosmic of Africa, with geographic extremes varying from sandy desert to tropical forest.

Recent evidence suggests that while most citizens of the country identify strongly with both Sudan and their religion, Arab and African supranational identities are much more polarising and contested.[211]

Music

A Sufi dervish drums up the Friday afternoon crowd in Omdurman.

Sudan has a rich and unique musical culture that has been through chronic instability and repression during the modern history of Sudan. Beginning with the imposition of strict Salafi interpretation of sharia law in 1989, many of the country's most prominent poets, like Mahjoub Sharif, were imprisoned while others, like Mohammed el Amin (returned to Sudan in the mid-1990s) and Mohammed Wardi (returned to Sudan 2003), fled to Cairo. Traditional music suffered too, with traditional Zār ceremonies being interrupted and drums confiscated [1]. At the same time European militaries contributed to the development of Sudanese music by introducing new instruments and styles; military bands, especially the Scottish bagpipes, were renowned, and set traditional music to military march music. The march March Shulkawi No 1, is an example, set to the sounds of the Shilluk. In northern Sudan different music from the rest of Sudan, is used as a type of music called (Aldlayib) used a musical instrument called (Tambur) are industry manually and has five strings and is made from wood and made wonderful music accompanied by the voices of human applause and singing artists give a perfect blend gives the area Northern State special character.

Sport

The most popular sports in Sudan are athletics (track and field) and football. Though not as successful as football, basketball, handball, and volleyball are also popular in Sudan. In the 1960s and 1970s, the national basketball team finished among the continent's top teams. Nowadays, it is only a minor force.

Sudanese football has a long history. Sudan was one of the four African nations – the others being Egypt, Ethiopia and South Africa – which formed African football. Sudan hosted the first African Cup of Nations in 1956, and has won the African Cup Of Nations once, in 1970. Two years later, the Sudan National Football Team participated in the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. The nation's capital is home to the Khartoum League, which is considered to be the oldest football league in Africa.

Sudanese football teams such as Al-Hilal, Al-Merrikh, and Abdelgadir Osman FC are among the nation's strongest teams. Other teams like Khartoum, El-Neel, Al-Nidal El-Nahud and Hay-Al Arab, are also starting to grow in popularity.

Clothing

Most individual Sudanese wear either traditional or western attire. A traditional garb widely worn in Sudan is the jalabiya, which is a loose-fitting, long-sleeved, collarless ankle-length garment also common to Egypt. The jalabiya is accompanied by a large scarf worn by women, and the garment may be white, colored, striped, and made of fabric varying in thickness, depending on the season of the year and personal preferences.

A similar garment common to Sudan is the thobe or thawb, pronounced tobe in Sudanese dialect. The thobe is a long one piece cloth that women wrap around their inner garments. The word "thawb" means "garment" in Arabic, and the thawb itself is the traditional Arab dress for men.

Media

Sudanese author Leila Aboulela

Sudanese tourists by the Meroë pyramids in various types of clothing.

Sudanese women in Darfur

Herders at the camel market on the far west side of Omdurman

Education

Khartoum University established in 1902

Education in Sudan is free and compulsory for children aged 6 to 13 years. Primary education consists of eight years, followed by three years of secondary education. The former educational ladder 6 + 3 + 3 was changed in 1990. The primary language at all levels is Arabic. Schools are concentrated in urban areas; many in the West have been damaged or destroyed by years of civil war. In 2001 the World Bank estimated that primary enrollment was 46 percent of eligible pupils and 21 percent of secondary students. Enrollment varies widely, falling below 20 percent in some provinces. The literacy rate is 70.2% of total population, male: 79.6%, female: 60.8%.[11]

Science and research

Sudan has around 25-30 universities; instruction is primarily in Arabic. Education at the secondary and university levels has been seriously hampered by the requirement that most males perform military service before completing their education.[212] In addition, the "islamization" encouraged by president Al-Bashir alienated many researchers: the official language of instruction in universities was changed from English to Arabic and Islamic courses became mandatory. Internal science funding withered.[213] According to UNESCO, more than 3000 Sudanese researchers left the country between 2002 and 2014. By 2013, the country had a mere 19 researchers for every 100,000 citizens, or 1/30 the ratio of Egypt, according to the Sudanese National Centre for Research. In 2015, Sudan published only about 500 scientific papers.[213] For comparison, Poland, a country of similar population size, publishes on the order of 10,000 papers per year.[214]

Health care

Sudan has a life expectancy of 64.5 years (62.9 for males and 66.1 for females) according to the latest data for the year 2016 from the World Bank.[215] Infant mortality in 2016 was 44.8 per 1,000.[216]

See also

- List of heads of government of Sudan

- Outline of Sudan

- Lost Boys of Sudan

- Society for the Study of the Sudans UK

- Sudan Studies Association

References

^ ab "2005 constitution in English" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2013..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Sudan" (PDF). Cairo Institute For Human Rights Studies.

^ Rayah, Mubarak B. (1978). Sudan civilization. Democratic Republic of the Sudan, Ministry of Culture and Information. p. 64.

^ ab "World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision". ESA.UN.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

^ "Discontent over Sudan census". News24. Cape Town. Agence France-Presse. 21 May 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

^ abcd "Sudan". International Monetary Fund.

^ "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

^ "2018 Human Development Report". United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

^ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521152532

^ abcdefgh "The World Factbook: Sudan". U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. ISSN 1553-8133. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

^ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

^ Davison, Roderic H. (1960). "Where is the Middle East?". Foreign Affairs. 38 (4): 665–675. doi:10.2307/20029452.

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 14 July 2017.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Collins, Robert O. (2008). A History of Modern Sudan. Cambridge University Press.

ISBN 978-0-521-85820-5.

^ International Association for the History of Religions (1959), Numen, Leiden: EJ Brill, p. 131,West Africa may be taken as the country stretching from Senegal in the West, to the Cameroons in the East; sometimes it has been called the central and western Sudan, the Bilad as-Sūdan, 'Land of the Blacks', of the Arabs

^ Sharkey 2007, pp. 29-32.

^ "Sudan A Country Study". Countrystudies.us.

^ Keita, S.O.Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20: 129–54. doi:10.2307/3171969. JSTOR 317196.

^ Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-193825-7.

^ Welsby 2002, p. 26.

^ Welsby 2002, pp. 16-22.

^ Welsby 2002, pp. 24, 26.

^ Welsby 2002, pp. 16-17.

^ Werner 2013, p. 77.

^ Welsby 2002, pp. 68-70.

^ Hasan 1967, p. 31.

^ Welsby 2002, pp. 77-78.

^ Shinnie 1978, p. 572.

^ Werner 2013, p. 84.

^ Werner 2013, p. 101.

^ Welsby 2002, p. 89.

^ Ruffini 2012, p. 264.

^ Martens-Czarnecka 2015, pp. 249-265.

^ Werner 2013, p. 254.

^ Edwards 2004, p. 237.

^ Adams 1977, p. 496.

^ Adams 1977, p. 482.

^ Welsby 2002, pp. 236-239.

^ Werner 2013, pp. 344-345.

^ Welsby 2002, p. 88.

^ Welsby 2002, p. 252.

^ Hasan 1967, p. 176.

^ Hasan 1967, p. 145.

^ Werner 2013, pp. 143-145.

^ Lajtar 2011, pp. 130-131.

^ Ruffini 2012, p. 256.

^ Welsby 2002, p. 255.

^ Vantini 1975, pp. 786–787.

^ Hasan 1967, p. 133.

^ Vantini 1975, p. 784.

^ Vantini 2006, pp. 487–489.

^ Spaulding 1974, pp. 12-30.

^ Holt & Daly 2000, p. 25.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 25-26.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 26.

^ Loimeier 2013, p. 150.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 31.

^ Loimeier 2013, pp. 151-152.

^ Werner 2013, pp. 177-184.

^ Peacock 2012, p. 98.

^ Peacock 2012, pp. 96-97.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 35.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 36-40.

^ Adams 1977, p. 601.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 78.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 88.

^ Spaulding 1974, p. 24-25.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 94-95.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 98.

^ Spaulding 1985, p. 382.

^ Loimeier 2013, p. 152.

^ Spaulding 1985, pp. 210-212.

^ Adams 1977, pp. 557–558.

^ Edwards 2004, p. 260.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, pp. 28-29.

^ Hesse 2002, p. 50.

^ Hesse 2002, pp. 21-22.

^ McGregor 2011, Table 1.

^ ab O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 110.

^ McGregor 2011, p. 132.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 123.

^ Holt & Daly 2000, p. 31.

^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, p. 126.

^ ab O'Fahey & Tubiana 2007, p. 9.

^ ab O'Fahey & Tubiana 2007, p. 2.

^ Churchill, Winston (1902). "The Rebellion of the Mahdi". The River War.

^ Rudolf Carl Freiherr von Slatin; Sir Francis Reginald Wingate (1896). Fire and Sword in the Sudan. E. Arnold. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

^ Domke, D. Michelle (November 1997). "ICE Case Studies; Case Number: 3; Case Identifier: Sudan; Case Name: Civil War in the Sudan: Resources or Religion?". Inventory of Conflict and Environment (via the American University School of International Service). Archived from the original on 9 December 2000. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

^ M. Daly, Empire on the Nile, p.346.

^ Morewood, The British Defence of Egypt, (Suffolk 2005), p.4

^ Daly, pp.457–59

^ Morewood,

The British Defence of Egypt 1935–40, (Suffolk, 1940), p.94-5

^ Arthur Henderson, 8 May 1936 quoted in Daly, Empire on the Nile, p.348

^ Sir Miles Lampson quoted in diary, 29 September 1938; Morewood, p.117

^ Morewood, p.164-5

^ "Brief History of the Sudan". Sudan Embassy in London. 20 November 2008. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

^ "Factbox – Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir". Reuters. 14 July 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2011.