Hurricane Iwa

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

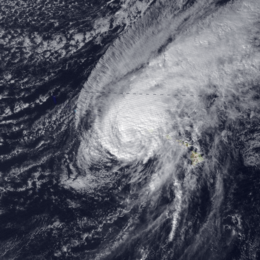

Hurricane Iwa brushing the northern Hawaiian Islands at peak intensity on November 24 | |

| Formed | November 19, 1982 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 25, 1982 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 90 mph (150 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 968 mbar (hPa); 28.59 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 direct, 3 indirect |

| Damage | $312 million (1982 USD) |

| Areas affected | Hawaii |

| Part of the 1982 Pacific hurricane season | |

Hurricane Iwa, taken from the Hawaiian language name for the frigatebird (ʻiwa, lit. "Thief"), was at the time the costliest hurricane to affect the state of Hawaiʻi. Iwa was the twenty-third tropical storm and the twelfth and final hurricane of the 1982 Pacific hurricane season. It developed from an active trough of low pressure near the equator on November 19. The storm moved erratically northward until becoming a hurricane on November 23 when it began accelerating to the northeast in response to strong upper-level flow from the north. Iwa passed within 25 miles of the island of Kauaʻi with peak winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) on November 23 (November 24 Coordinated Universal Time), and the next day it became extratropical to the northeast of the state.

The hurricane devastated the islands of Niʻihau, Kauaʻi, and Oʻahu with wind gusts exceeding 100 mph (160 km/h) and rough seas exceeding 30 feet (9 m) in height. The first significant hurricane to hit the Hawaiian Islands since statehood in 1959, Iwa severely damaged or destroyed 2,345 buildings, including 1,927 houses, leaving 500 people homeless. Damage throughout the state totaled $312 million (1982 USD, $792 million 2018 USD). One person was killed from the high seas, and three deaths were indirectly related to the hurricane's aftermath.

Contents

1 Meteorological history

2 Impact

3 Aftermath

3.1 Retirement

4 See also

5 References

Meteorological history

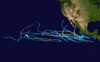

Map plotting the track and the intensity of the storm, according to the Saffir–Simpson scale

A very active trough of low pressure persisted along the equator in the middle of November, with westerly surface winds and windspread convection located along the trough from 140° W to 140° E. An organized circulation developed near Palmyra Atoll on November 18, and steadily developed as it drifted westward.[1] Though very late in the season, warm temperatures to the south of the Hawaiian Islands due to the strongest El Nino in many years allowed the disturbance to develop into Tropical Storm Iwa on November 19 while located about 970 miles (1,760 km) southwest of the southernmost point in Hawaii. The storm tracked slowly northward after forming and initially remained a weak tropical storm. After turning to the northeast, Iwa began slowly intensifying, and on November 23 after turning to the north-northwest Iwa strengthened into a hurricane while located 580 miles (930 km) southwest of the southern tip of Hawaii.[1][2]

Shortly after becoming a hurricane, Iwa turned and accelerated to the northeast in response to strong upper level flow to its north. The hurricane possessed sufficient moisture, instability, and upper divergence for continued intensification, and Iwa reached peak winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) late on November 23 while located 245 miles (395 km) southwest of Waimea on the island of Kauaʻi. Its forward speed increased to 30 to 40 mph, and Iwa passed just north of the island of Kauai on November 23 (November 24 in UTC). The right semicircle of the storm extended across Kauaʻi and Oʻahu, with gusts from 100 to 120 mph (161 to 193 km/h). After passing Hawaii, the convection of Iwa rapidly deteriorated as it gradually lost tropical characteristics. Late on November 24, the hurricane degenerated into a tropical storm, and on November 25 Iwa became an extratropical cyclone while located about 600 miles (965 km) northeast of Hawaii.[2]

Impact

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 1321 | 52.02 | Lane 2018 | Mountainview, Hawaii | [3] |

| 2 | 1321 | 52.00 | Hiki 1950 | Kanalohuluhulu Ranger Station | [4] |

| 3 | 985 | 38.76 | Paul 2000 | Kapapala Ranch 36 | [5] |

| 4 | 635 | 25.00 | Maggie 1970 | Various stations | [6] |

| 5 | 519 | 20.42 | Nina 1957 | Wainiha | [7] |

| 6 | 516 | 20.33 | Iwa 1982 | Intake Wainiha 1086 | [8] |

| 7 | 476 | 18.75 | Fabio 1988 | Papaikou Mauka 140.1 | [8] |

| 8 | 387 | 15.25 | Iselle 2014 | Kulani NWR | [9] |

| 9 | 381 | 15.00 | One-C 1994 | Waiakea Uka, Piihonua | [10] |

| 10 | 372 | 14.63 | Felicia 2009 | Oahu Forecast National Wildlife Refuge | [11] |

Hurricane Iwa produced estimated gusts reaching 120 mph (193 km/h) across Kauaʻi and Oʻahu. The acceleration of the hurricane concentrated the energy of its swells, resulting in high waves and storm surge across the Hawaiian Islands, though primarily near the path of the center. It is estimated the storm surge reached eight feet (two meters) on the south coast of Kauaʻi.[2] There, the surge reached 900 feet (275 m) inland, exceeding a 100-year flood event for the area.[12] The heaviest rainfall reported from the island chain was from the Intake Wainiha 1086 site, where 20.33 inches (516 mm) was measured.[8] Possible tornadoes were reported in association with a rain squall in Oʻahu.[2] Waves on the coast of Oʻahu reached 16.4 feet in height (3 m),[13] and waves on southern Kauaʻi surpassed 30 feet (9 m) in height.[14]

Hurricane Iwa passing just north of Kauaʻi on November 24

During the worst of the storm, 5,800 people were evacuated from shoreline areas of Kauaʻi to temporary shelters. Strong waves sank or grounded several small vessels on the southwestern coast of Kauaʻi,[2] with 44 of the 45 boats at Port Allen being sunk.[14] The worst of the damage from the hurricane occurred in Poipu, where the rough surf destroyed or severely damaged several exposed luxury hotels and condominiums. Elsewhere on the island, damage was greatest in areas where there was no protective barrier reef offshore. Several small aircraft were damaged at Lihue airport from the winds, including many overturned small planes.[2] The winds destroyed several buildings across the island, including one of Kauaʻi's oldest churches and a warehouse. Additionally, the winds destroyed the roof of a bank.[15] Strong winds initially left the entire island of Kauaʻi without power.[16] Highway 56 on the east side of the island was obstructed by fallen telephone poles, forcing residents to drive on the unpaved, red dirt cane roads usually reserved for hauling sugar cane from the fields. Rising waters washed out multiple roads near the coastline. The strong winds destroyed nearly all papaya and banyan trees on the island.[17] The hurricane destroyed or greatly damaged 1,907 homes on the island and caused minor damage to 2,983 others, leaving one-eighth of the island's homes unlivable.[18]

Rough seas killed a person on a Navy Destroyer the USS Goldsborough DDG-20 in Pearl Harbor when the seaman hit a stanchion,[1] with four others injured on the ship. One of the four injured was swept overboard two miles (three kilometers) from the harbor. Before the arrival of the hurricane, around 1,000 evacuated the low-lying coastline to shelters.[15]

Rough waves destroyed four and damaged two deep-water communication cables between Oʻahu and Kauaʻi.[13] In Oʻahu, damage from wind and surf was heaviest on the southwest coast between Nānākuli and Mākaha. The storm surge washed sand into streets in Waikīkī and flooded cars in areas of basement parking. Wind damage was greatest in areas where winds blew from southerly directions off of mountains. The winds damaged several small aircraft and a Douglas DC-3 plane in Honolulu. Gusty winds shattered glass windows in the Honolulu International Airport, injuring several passengers.[2] Some flights in and out of the Honolulu airport were delayed, while other domestic airports were temporarily closed.[15] The passage of the hurricane damaged at least 6,391 homes, 21 hotels, and two condominium buildings on the island.[19] Additionally, 418 buildings, including 30 businesses, were destroyed on Oʻahu.[18]

Surf damage was reported throughout the Hawaiian islands.[2] 120 people were treated for injuries,[15] though most were minor.[2] An estimated 500 people throughout Hawaii were left homeless due to the hurricane.[15] Damage on the private island of Niʻihau was severe. An aerial survey indicated 20 homes were destroyed and 160 were damaged, indicating that the hurricane affected nearly all of the island's 226 residents. Reportedly no one was injured on Niʻihau.[18] At the time, Hurricane Iwa was the costliest storm to hit the state of Hawaiʻi,[12] with damage totaling $312 million (1982 USD, $792 million 2018 USD).[20]

Aftermath

Three days after Hurricane Iwa passed the state, Governor George Ariyoshi declared the islands of Kauai and Niʻihau as disaster areas and began filing papers for a federal disaster declaration.[21] On November 28, five days after the hurricane struck, President Ronald Reagan declared the islands of Kauaʻi, Niʻihau, and Oʻahu as a disaster area. The declaration allocated federal funds to aid the affected citizens.[19] The state Department of Education decided to close all schools on Kauaʻi indefinitely.[18]

The thousands of residents without power celebrated Thanksgiving by cooking turkeys on outdoor grills or smokers. Army and Air Force planes delivered 20,000 Thanksgiving rations to the thousands left in temporary shelters. The United States military also airlifted generators to Kauaʻi due to several days of power outages.[21] By three weeks after the hurricane, utility crews restored power to nearly all major areas in Oʻahu, while 5,000 remained without power in Kauaʻi.[18] By around a month after the hurricane passed the island, utilities were restored to most of the entire island. All roads and highways were cleared, as well.[17] One 25th Infantry Division soldier at Schofield Barracks died while cleaning up after the hurricane.[1] Two people died in a traffic accident due to malfunctioning traffic lights.[22] Following the storm, significant redevelopment occurred in Poipu, where the hurricane flooded areas several hundred feet inland. Hurricane Iniki struck the same area ten years later. Officials estimate a hurricane similar to Iwa striking Oʻahu in 1992 could cause up to $7.5 billion in damage (USD).[23]

Retirement

The Central Pacific Hurricane Center retired the name Iwa subsequent to the storm and replaced it with Io. However, in 2007, the CPHC revised the four rotating lists of tropical cyclone names and replaced the name Io with Iona before it could be used.[24] Iwa was the first retired hurricane in the Central Pacific since the modern system of using Hawaiian naming began in the early 1980s, and it remains one of only four to be retired as of 2015.[25]

See also

- Hurricane Dot (1959)

- Hurricane Iniki

- Hurricane Lane (2018)

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- List of Hawaii hurricanes

- List of retired Pacific hurricane names

References

^ abcd Central Pacific Hurricane Center (1982). "1982 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season". Retrieved 2006-12-17..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcdefghi Mariners Weather Log (1983). "Hurricane Iwa". Retrieved 2006-12-17.

^ Lane Possibly Breaks Hawaii Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Record (Public Information Statement). National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. August 27, 2018. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

^ Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Tropical Cyclones During the Years 1900-1952 (Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved January 26, 2007.

^ Roth, David M.; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Remains of Paul". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima (GIF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

^ Central Pacific Hurricane Center. The 1970 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

^ Central Pacific Hurricane Center. The 1957 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

^ abc Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

^ "Iselle Brought Heavy Rainfall and Flooding to Hawaii". National Weather Service Office in Honolulu, Hawaii. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 10, 2014. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

^ Central Pacific Hurricane Center. The 1994 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWSTM PR-41). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

^ Kimberlain, Todd B; Wroe Derek; Knabb, Richard D; National Hurricane Center; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (January 10, 2010). Hurricane Felicia (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. p. 3. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

^ ab United States Geological Survey (2005). "Summary of Significant Floods, 1982". Archived from the original on 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ ab A. T. Dengler; P. Wilde; E. K. Noda; W. R. Normark (1997). "Turbidity Currents Generated by Hurricane IWA". Geo-Marine Letters. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ ab Anthony Sommer (2002). "Lessons Learned from Iniki leave officials better prepared for any future disasters". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ abcde United Press International (1982-11-25). "One Dead in Hawaii Storm; Damage to 3 Islands Severe". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ United Press International (1982-11-24). "Hurricane Iwa Hits Hawaiian Island of Kauai". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ ab United Press International (1982-12-19). "Kauai Recovering from Punishment Sustained from Hurricane in November".

^ abcde United Press International (1982-11-30). "Power Still Out in Parts of Kauai". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ ab United Press International (1982-11-28). "Hawaii Hurricane Path Declared Disaster Area". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ Eric S. Blake; Edward N. Rappaport; Christopher W. Landsea (April 2007). "THE DEADLIEST, COSTLIEST, AND MOST INTENSE UNITED STATES TROPICAL CYCLONES FROM 1851 TO 2006 (AND OTHER FREQUENTLY REQUESTED HURRICANE FACTS)" (PDF). p. 26. Retrieved 2007-04-11.

^ ab United Press International (1982-11-26). "Hawaii Storm Cost Near $200 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ Michael Tsai (2006-07-02). "Hurricane Iwa". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ Charles Fletcher; Eric Grossman; Bruce Richmond (2000). "Hawaii Hazard Mitigation Forum". Archived from the original on 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2006-12-22.

^ Padgett, Gary; Boyle, Kevin; Clarke, Simon; Bath, Michael. "MONTHLY GLOBAL TROPICAL CYCLONE SUMMARY NOVEMBER 2007". National Hurricane Center. NHC. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

^ Atlantic Tropical Weather Center (2006). "Tropical Cyclone Retirement". Ablaze Productions, Inc. Retrieved 2006-12-23.