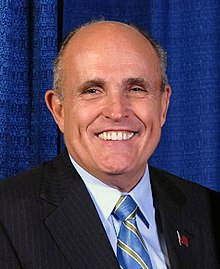

Rudy Giuliani

Rudy Giuliani KBE | |

|---|---|

| |

| 107th Mayor of New York City | |

In office January 1, 1994 – December 31, 2001 | |

| Preceded by | David Dinkins |

| Succeeded by | Michael Bloomberg |

| United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York | |

In office June 3, 1983 – January 1, 1989 | |

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | John S. Martin Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Benito Romano (Acting) |

| United States Associate Attorney General | |

In office February 20, 1981 – June 3, 1983 | |

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | John Shenefield |

| Succeeded by | D. Lowell Jensen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Rudolph William Louis Giuliani (1944-05-28) May 28, 1944 Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican (1980–present) |

| Other political affiliations | Independent (1975–1980) Democratic (before 1975) |

| Spouse(s) | Regina Peruggi (1968–1982) Donna Hanover (1984–2002) Judith Nathan (2003–present); divorce filed in 2018 |

| Children | 2 (including Andrew) |

| Education | Manhattan College (BA) New York University (JD) |

| Signature |  |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Mayor of New York City

| ||

Rudolph William Louis Giuliani (/ˌdʒuːliˈɑːni/, Italian: [dʒuˈljaːni]; born May 28, 1944) is an American politician, attorney, businessman and public speaker who served as the 107th Mayor of New York City from 1994 to 2001. He currently acts as an attorney to President Donald Trump.[1] Politically a Democrat, then an Independent in the 1970s and a Republican since the 1980s, Giuliani served as United States Associate Attorney General from 1981 to 1983. That year he became the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, holding the position until 1989.[2] He prosecuted cases against the American Mafia and against corrupt corporate financiers.

When Giuliani took office as Mayor of New York City, he appointed a new police commissioner, William Bratton, who applied the broken windows theory of urban decay, which holds that minor disorders and violations create a permissive atmosphere that leads to further and more serious crimes that can threaten the safety of a city.[3] Within several years, Giuliani was widely credited for making major improvements in the city's quality of life and lowering the rate of violent crimes.[3] While Giuliani was still Mayor, he ran for the United States Senate in 2000; however, he withdrew from the race upon learning of his prostate cancer diagnosis.[4] Giuliani was named Time magazine's Person of the Year for 2001,[5] and was given an honorary knighthood in 2002 by Queen Elizabeth II[6] for his leadership in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001.

In 2002, Giuliani founded Giuliani Partners (consulting), acquired and later sold Giuliani Capital Advisors (investment banking), and joined a Texas firm while opening a Manhattan office for the firm renamed Bracewell & Giuliani (legal services). Giuliani sought the Republican Party's 2008 presidential nomination, and was considered the early front runner in the race,[7] before withdrawing from the race to endorse the eventual nominee, John McCain. Giuliani was considered a potential candidate for New York Governor in 2010[8][9] and for the Republican presidential nomination in 2012.[10] Giuliani declined all races, and instead remained in the business sector.[11][12][13] In April 2018, Giuliani became one of President Trump's personal lawyers.[14] Since then, he has appeared in the media in defense of Trump.

Contents

1 Early life

2 Legal career

2.1 Mafia Commission trial

2.2 Boesky, Milken trials

3 Mayoral campaigns

3.1 1989

3.2 1993

3.3 1997

4 Mayoralty

4.1 Law enforcement

4.2 City services

4.3 Appointees as defendants

4.4 2000 U.S. Senate campaign

4.5 September 11 terrorist attacks

4.5.1 Response

4.5.2 Communication preparedness

4.5.3 Public reaction

4.5.4 Time Person of the Year

4.5.5 Aftermath

5 Post-mayoralty

5.1 Politics

5.1.1 Before 2008 election

5.1.2 2008 presidential campaign

5.1.3 After 2008 election

5.1.4 Relationship with Donald Trump

5.1.4.1 Presidential campaign supporter

5.1.4.2 Advisor to the President

5.1.4.3 Personal lawyer

5.2 Giuliani Partners

5.3 Bracewell & Giuliani

5.4 Greenberg Traurig

5.5 Other lobbying

6 Personal life

6.1 Marriages and relationships

6.2 Prostate cancer

6.3 Religion and beliefs

7 Awards and honors

8 Media references

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Early life

Giuliani was born in an Italian-American enclave in East Flatbush in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, the only child of working-class parents, Harold Angelo Giuliani (1908–1981) and Helen Giuliani (née D'Avanzo; 1909–2002), both children of Italian immigrants.[15] Giuliani is of Tuscan origins from his father side, as his paternal grandparents (Rodolfo and Evangelina Giuliani) were born in Montecatini, Tuscany, Italy.[16] He was raised a Roman Catholic.[17] Harold Giuliani, a plumber and a bartender,[18] had trouble holding a job, and was convicted of felony assault and robbery, serving time in Sing Sing.[19] After his release he worked as an enforcer for his brother-in-law Leo D'Avanzo, who ran an organized crime operation involved in loan sharking and gambling at a restaurant in Brooklyn.[20] The family lived in East Flatbush, Brooklyn until Harold died of prostate cancer in 1981,[21] after which Helen moved to Manhattan's Upper East Side. Helen was featured in a television commercial to promote her son in the 1993 Mayoral Election.[21]

When Giuliani was seven years old in 1951, his family moved from Brooklyn to Garden City South, where he attended the local Catholic school, St. Anne's.[22] Later, he commuted back to Brooklyn to attend Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School, graduating in 1961.[23]

Giuliani attended Manhattan College in Riverdale, Bronx, where he majored in political science with a minor in philosophy[24] and considered becoming a priest.[24]

Giuliani was elected president of his class in his sophomore year, but was not re-elected in his junior year. He joined the Phi Rho Pi fraternity. He graduated in 1965. Giuliani decided to forego the priesthood and instead attended the New York University School of Law in Manhattan, where he made the NYU Law Review[24] and graduated cum laude with a Juris Doctor degree in 1968.[25]

Giuliani started his political life as a Democrat. He volunteered for Robert F. Kennedy's presidential campaign in 1968. He also worked as a Democratic Party committeeman on Long Island in the mid-1960s[26][27] and voted for George McGovern for president in 1972.[28]

Legal career

Giuliani greeting President Ronald Reagan in 1984

Upon graduation, Giuliani clerked for Judge Lloyd Francis MacMahon, United States District Judge for the Southern District of New York.[29]

Giuliani did not serve in the military during the Vietnam War. His conscription was deferred while he was enrolled at Manhattan College and NYU Law. Upon graduation from the latter in 1968, he was classified by the Selective Service System as 1-A (available for military service). He applied for a deferment but was rejected. In 1969, Judge MacMahon wrote a letter to Giuliani's draft board, asking that he be reclassified as 2-A (civilian occupation deferment), because Giuliani, who was a law clerk for MacMahon, was an essential employee. The deferment was granted. In 1970, Giuliani received a high draft lottery number; he was not called up for service although by then he had been reclassified 1-A.[30][31]

In 1975, Giuliani switched his party registration from Democratic to Independent[27] as he was recruited to Washington, D.C. during the Ford administration, where he was named Associate Deputy Attorney General and chief of staff to Deputy Attorney General Harold "Ace" Tyler.[27] His first high-profile prosecution was of Democratic U.S. Representative Bertram L. Podell (NY-13), who was convicted of corruption.[32] From 1977 to 1981, during the Carter administration, Giuliani practiced law at the Patterson, Belknap, Webb and Tyler law firm, as chief of staff to his previous DC boss, Ace Tyler. Tyler later became critical of Giuliani's turn as a prosecutor, calling his tactics "overkill".[27]

On December 8, 1980, one month after the election of Ronald Reagan brought Republicans back to power in Washington, he switched his party affiliation from Independent to Republican.[27] Giuliani later said the switches were because he found Democratic policies "naïve", and that "by the time I moved to Washington, the Republicans had come to make more sense to me".[15] Others suggested that the switches were made in order to get positions in the Justice Department.[27] Giuliani's mother maintained in 1988 that:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

He only became a Republican after he began to get all these jobs from them. He's definitely not a conservative Republican. He thinks he is, but he isn't. He still feels very sorry for the poor.[27]

In 1981, Giuliani was named Associate Attorney General in the Reagan administration,[33] the third-highest position in the Department of Justice. As Associate Attorney General, Giuliani supervised the U.S. Attorney Offices' federal law enforcement agencies, the Department of Corrections, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the United States Marshals Service. In a well-publicized 1982 case, Giuliani testified in defense of the federal government's "detention posture" regarding the internment of over 2,000 Haitian asylum seekers who had entered the country illegally. The U.S. government disputed the assertion that most of the detainees had fled their country due to political persecution, alleging instead that they were "economic migrants". In defense of the government's position, Giuliani testified that "political repression, at least in general, does not exist" under President of Haiti Jean-Claude Duvalier's regime.[24][34]

In 1983, Giuliani was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, which was technically a demotion but was sought by Giuliani because of his desire to personally litigate cases. It was in this position that he first gained national prominence by prosecuting numerous high-profile cases, resulting in the convictions of Wall Street figures Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken. He also focused on prosecuting drug dealers, organized crime, and corruption in government.[25] He amassed a record of 4,152 convictions and 25 reversals. As a federal prosecutor, Giuliani was credited with bringing the "perp walk", parading of suspects in front of the previously alerted media, into common use as a prosecutorial tool.[35] After Giuliani "patented the perp walk", the tool was used by increasing numbers of prosecutors nationwide.[36]

Giuliani's critics claimed that he arranged for people to be arrested, then dropped charges for lack of evidence on high-profile cases rather than going to trial. In a few cases, his arrests of alleged white-collar criminals at their workplaces with charges later dropped or lessened, sparked controversy, and damaged the reputations of the alleged "perps".[37] He claimed veteran stock trader Richard Wigton, of Kidder, Peabody & Co., was guilty of insider trading; in February 1987 he had officers handcuff Wigton and march him through the company's trading floor, with Wigton in tears.[38] Giuliani had his agents arrest Tim Tabor, a young arbitrageur and former colleague of Wigton, so late that he had to stay overnight in jail before posting bond.[38][39]

Within three months, charges were dropped against both Wigton and Tabor; Giuliani said, "We're not going to go to trial. We're just the tip of the iceberg", but no further charges were forthcoming and the investigation did not end until Giuliani's successor was in place.[39] Giuliani's high-profile raid of the Princeton/Newport firm ended with the defendants having their cases overturned on appeal on the grounds that what they had been convicted of were not crimes.[40]

Mafia Commission trial

In the Mafia Commission Trial (February 25, 1985 – November 19, 1986), Giuliani indicted eleven organized crime figures, including the heads of New York's so-called "Five Families", under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) on charges including extortion, labor racketeering, and murder for hire. Time magazine called this "Case of Cases" possibly "the most significant assault on the infrastructure of organized crime since the high command of the Chicago Mafia was swept away in 1943", and quoted Giuliani's stated intention: "Our approach is to wipe out the five families."[41]Gambino crime family boss Paul Castellano evaded conviction as he was murdered on December 16, 1985, alongside his underboss, Thomas Bilotti, the murders were orchestrated by up-and-coming mobster John Gotti who took over the Gambino family and would later be sentenced to life without parole in 1992 for the murder and numerous other crimes. However 4 heads of the Five Families were sentenced to 100 years in prison on January 13, 1987.[42][43]

According to an FBI memo revealed in 2007, leaders of the five New York mob families voted in late 1986 on whether to issue a contract for Giuliani's death.[44] Heads of the Lucchese, Bonanno, and Genovese families rejected the idea, though Colombo and Gambino leaders, Carmine Persico and John Gotti encouraged assassination.[45][46] In 2014, it was revealed by former Sicilian Mafia member and informant, Rosario Naimo, that Salvatore Riina, a notorious Sicilian Mafia leader, had ordered a murder contract on Giuliani during the mid-1980s. Riina allegedly became suspicious of his efforts against prosecuting the American Mafia and was worried that Giuliani might have spoken with Italian anti-mafia prosecutors and politicians, including Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, who would both later be murdered in 1992 in separate car bombings.[47][48] According to Giuliani, the Sicilian Mafia offered $800,000 for his death during his first year as Mayor of New York in 1994.[49][50]

Boesky, Milken trials

Ivan Boesky was a Wall Street arbitrageur who had amassed a fortune of about $200 million by betting on corporate takeovers. He was investigated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for making investments based on tips received from corporate insiders. These stock and options acquisitions were sometimes brazen, with massive purchases occurring only a few days before a corporation announced a takeover. Although insider trading of this kind was illegal, laws prohibiting it were rarely enforced until Boesky was prosecuted. Boesky cooperated with the SEC and informed on several others, including junk bond trader Michael Milken. Per agreement with Giuliani, Boesky received a 3 1⁄2-year prison sentence along with a $100 million fine.[51] In 1989, Giuliani charged Milken under the RICO Act with 98 counts of racketeering and fraud. In a highly publicized case, Milken was indicted by a grand jury on these charges.[52]

Mayoral campaigns

Giuliani was U.S. Attorney until January 1989, resigning as the Reagan administration ended. He garnered criticism until he left office for his handling of cases, and was accused of prosecuting cases to further his political ambitions.[24] He joined the law firm White & Case in New York City as a partner. He remained with White & Case until May 1990, when he joined the law firm Anderson Kill Olick & Oshinsky, also in New York City.[53]

1989

Giuliani first ran for New York City Mayor in 1989, when he attempted to unseat three-term incumbent Ed Koch. He won the September 1989 Republican Party primary election against business magnate Ronald Lauder, in a campaign marked by claims that Giuliani was not a true Republican and by an acrimonious debate.[54] In the Democratic primary, Koch was upset by Manhattan Borough President David Dinkins.

In the general election, Giuliani ran as the fusion candidate of both the Republican and Liberal Parties. The Conservative Party, which had often co-lined the Republican party candidate, withheld support from Giuliani and ran Lauder instead.[55] Conservative Party leaders were unhappy with Giuliani on ideological grounds. They cited the Liberal Party's endorsement statement that Giuliani

"agreed with the Liberal Party's views on affirmative action, gay rights, gun control, school prayer and tuition tax credits."[56]

During two televised debates, Giuliani framed himself as an agent of change, saying, "I'm the reformer",[57] that "If we keep going merrily along, this city's going down", and that electing Dinkins would represent "more of the same, more of the rotten politics that have been dragging us down".[54] Giuliani pointed out that Dinkins had not filed a tax return for many years and of several other ethical missteps, in particular a stock transfer to his son.[57] Dinkins filed several years of returns and said the tax matter had been fully paid off, denied other wrongdoing, and said that "what we need is a mayor, not a prosecutor", and that Giuliani refused to say "the R-word—he doesn't like to admit he's a Republican."[57] Dinkins won the endorsements of three of the four daily New York newspapers, while Giuliani won approval from the New York Post.[58]

In the end, Giuliani lost to Dinkins by a margin of 47,080 votes out of 1,899,845 votes cast, in the closest election in New York City's history. The closeness of the race was particularly noteworthy considering the small percentage of New York City residents who are registered Republicans and resulted in Giuliani being the presumptive nominee for a re-match with Dinkins at the next election.[25]

1993

Four years after he was beaten by Dinkins, Giuliani again ran for mayor. Once again, Giuliani also ran on the Liberal Party line but not the Conservative Party line, which ran activist George Marlin.[59] The city was suffering from a spike in unemployment associated with the nationwide recession, with local unemployment rates going from 6.7% in 1989 to 11.1% in 1992, although crime rates had already begun to decline under Dinkins.[60][61][62]

Giuliani promised to focus the police department on shutting down petty crimes and nuisances as a way of restoring the quality of life:

It's the street tax paid to drunks and panhandlers. It's the squeegee men shaking down the motorist waiting at a light. It's the trash storms, the swirling mass of garbage left by peddlers and panhandlers, and open-air drug bazaars on unclean streets.[63]

Dinkins and Giuliani never debated during the campaign, because they were never able to agree on how to approach a debate.[54][59] Dinkins was endorsed by The New York Times and Newsday,[64] while Giuliani was endorsed by the New York Post and, in a key switch from 1989, the Daily News.[65] Giuliani came to visit the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, seeking his blessing and endorsement.[66]

Giuliani won by a margin of 53,367 votes. He became the first Republican elected Mayor of New York City since John Lindsay in 1965.[67]

1997

Giuliani's opponent in 1997 was Democratic Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger, who had beaten Al Sharpton in the September 9, 1997 Democratic primary.[68] In the general election, Giuliani once again had the Liberal Party and not the Conservative Party listing. Giuliani ran an aggressive campaign, parlaying his image as a tough leader who had cleaned up the city. Giuliani's popularity was at its highest point to date, with a late October 1997 Quinnipiac University Polling Institute poll showing him as having a 68 percent approval rating; 70 percent of New Yorkers were satisfied with life in the city and 64 percent said things were better in the city compared to four years previously.[69]

Throughout the campaign he was well ahead in the polls and had a strong fund-raising advantage over Messinger. On her part, Messinger lost the support of several usually Democratic constituencies, including gay organizations and large labor unions.[70] The local daily newspapers—The New York Times, Daily News, New York Post and Newsday—all endorsed Giuliani over Messinger.[71]

In the end, Giuliani won 59% of the vote to Messinger's 41%, and became the first registered Republican to win a second term as mayor while on the Republican line since Fiorello H. La Guardia in 1941.[68] Voter turnout was the lowest in 12 years, with 38% of registered voters casting ballots.[72] The margin of victory included gains[73] in his share of the African American vote (20% compared to 1993's 5%) and the Hispanic vote (43% from 37%) while maintaining his base of white ethnic, Catholic and Jewish voters from 1993.[73]

Mayoralty

Giuliani served as mayor of New York City from 1994 through 2001.

Rudy Giuliani with President Bill Clinton in 1993

Law enforcement

In Giuliani's first term as mayor, the New York City Police Department—at the instigation of Commissioner Bill Bratton—adopted an aggressive enforcement/deterrent strategy based on James Q. Wilson's "Broken Windows" approach.[74] This involved crackdowns on relatively minor offenses such as graffiti, turnstile jumping, cannabis possession, and aggressive panhandling by "squeegee men", on the theory that this would send a message that order would be maintained. The legal underpinning for removing the "squeegee men" from the streets was developed under Giuliani's predecessor, Mayor David Dinkins.[74] Bratton, with Deputy Commissioner Jack Maple, also created and instituted CompStat, a computer-driven comparative statistical approach to mapping crime geographically and in terms of emerging criminal patterns, as well as charting officer performance by quantifying criminal apprehensions.[75] Critics of the system assert that it creates an environment in which police officials are encouraged to underreport or otherwise manipulate crime data. An extensive study found a high correlation between crime rates reported by the police through CompStat and rates of crime available from other sources, suggesting there had been no manipulation.[76] The CompStat initiative won the 1996 Innovations in Government Award from the Kennedy School of Government.[77]

National, New York City, and other major city crime rates (1990–2002).[78]

During Giuliani's administration, crime rates dropped in New York City.[76] The extent to which Giuliani deserves the credit is disputed.[79] Crime rates in New York City had started to drop in 1991 under previous mayor David Dinkins, three years before Giuliani took office.[80][81] The rates of most crimes, including all categories of violent crime, made consecutive declines during the last 36 months of Dinkins's four-year term, ending a 30-year upward spiral.[82] A small nationwide drop in crime preceded Giuliani's election, and some critics say that he may have been the beneficiary of a trend already in progress. Additional contributing factors to the overall decline in New York City crime during the 1990s were the addition of 7,000 officers to the NYPD, lobbied for and hired by the Dinkins administration, and an overall improvement in the national economy.[83] Changing demographics were a key factor contributing to crime rate reductions, which were similar across the country during this time.[84] Because the crime index is based on that of the FBI, which is self-reported by police departments, some have alleged that crimes were shifted into categories that the FBI doesn't collect.[85]

Giuliani's supporters cite studies concluding that the decline in New York City's crime rate in the 1990s and 2000s exceeds all national figures and therefore should be linked with a local dynamic that was not present as such anywhere else in the country: what University of California sociologist Frank Zimring calls "the most focused form of policing in history". In his book The Great American Crime Decline, Zimring argues that "up to half of New York's crime drop in the 1990s, and virtually 100 percent of its continuing crime decline since 2000, has resulted from policing."[86][87]

Bratton was featured on the cover of Time Magazine in 1996.[88] Giuliani reportedly forced Bratton out after two years, in what was seen as a battle of two large egos in which Giuliani was not tolerant of Bratton's celebrity.[89][90] Bratton went on to become chief of the Los Angeles Police Department.[91] Giuliani's term also saw allegations of civil rights abuses and other police misconduct under other commissioners after Bratton's departure. There were police shootings of unarmed suspects,[92] and the scandals surrounding the torture of Abner Louima and the killings of Amadou Diallo, Gidone Busch[93] and Patrick Dorismond. Giuliani supported the New York City Police Department, for example by releasing what he called Dorismond's "extensive criminal record" to the public, including a sealed juvenile file.[94]

City services

The Giuliani administration advocated the privatization of failing public schools and increasing school choice through a voucher-based system.[95] Giuliani supported protection for illegal immigrants. He continued a policy of preventing city employees from contacting the Immigration and Naturalization Service about immigration violations, on the grounds that illegal aliens should be able to take actions such as sending their children to school or reporting crimes to the police without fear of deportation.[96]

During his mayoralty, gay and lesbian New Yorkers received domestic partnership rights. Giuliani induced the city's Democratic-controlled New York City Council, which had avoided the issue for years, to pass legislation providing broad protection for same-sex partners. In 1998, he codified local law by granting all city employees equal benefits for their domestic partners.[97]

Appointees as defendants

Several of Giuliani's appointees to head City agencies became defendants in criminal proceedings.

In 2000, Giuliani appointed 34-year-old Russell Harding, the son of Liberal Party of New York leader and longtime Giuliani mentor Raymond Harding, to head the New York City Housing Development Corporation, although Harding had neither a college degree nor relevant experience. In 2005, Harding pleaded guilty to defrauding the Housing Development Corporation and to possession of child pornography. He was sentenced to five years in prison.[98] Russell Harding committed suicide in 2012.[99]

In a related matter, Richard Roberts, appointed by Giuliani as Housing Commissioner and as chairman of the Health and Hospitals Corporation, pleaded guilty to perjury after lying to a grand jury about a car that Harding bought for him with City funds.[100]

Giuliani was a longtime backer of Bernard Kerik, who started out as an NYPD detective driving for Giuliani's campaign. Giuliani appointed him as the Commissioner of the Department of Correction and then as the Police Commissioner. Giuliani was also the godfather to Kerik's two youngest children.[101] After Giuliani left office, Kerik was subject to state and federal investigations resulting in his pleading guilty in 2006, in a Bronx Supreme Court, to two unrelated ethics violations. Kerik was ordered to pay $221,000 in fines. Kerik then pleaded guilty in 2009, in a New York district court, to eight federal charges, including tax fraud and false statements, and on February 18, 2010, he was sentenced to four years in federal prison.[102] Giuliani was not implicated in any of the proceedings.

2000 U.S. Senate campaign

Giuliani campaigned for Senate in 2000 before withdrawing after being diagnosed with cancer

Due to term limits, Giuliani could not run in 2001 for a third term as mayor. In November 1998, four-term incumbent Democratic U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan announced his retirement and Giuliani immediately indicated an interest in running in the 2000 election for the now-open seat. Due to his high profile and visibility Giuliani was supported by the state Republican Party. Giuliani's entrance led Democratic Congressman Charles Rangel and others to recruit then-U.S. First Lady Hillary Clinton to run for Moynihan's seat, hoping she might combat his star power.

An early January 1999 poll showed Giuliani trailing Clinton by 10 points.[103] In April 1999, Giuliani formed an exploratory committee in connection with the Senate run. By January 2000, Giuliani had reversed the polls situation, pulling nine points ahead after taking advantage of several campaign stumbles by Clinton.[103] Nevertheless, the Giuliani campaign was showing some structural weaknesses; so closely identified with New York City, he had somewhat limited appeal to normally Republican voters in Upstate New York.[104] The New York Police Department's fatal shooting of Patrick Dorismond in March 2000 inflamed Giuliani's already strained relations with the city's minority communities,[105] and Clinton seized on it as a major campaign issue.[105] By April 2000, reports showed Clinton gaining upstate and generally outworking Giuliani, who stated that his duties as mayor prevented him from campaigning more.[106] Clinton was now 8 to 10 points ahead of Giuliani in the polls.[105]

Then followed four tumultuous weeks, in which Giuliani's medical life, romantic life, marital life, and political life all collided at once in a most visible fashion. Giuliani discovered that he had prostate cancer and needed treatment; his extramarital relationship with Judith Nathan became public and the subject of a media frenzy; he announced a separation from his wife Donna Hanover; and, after much indecision, on May 19, 2000 he announced his withdrawal from the Senate race.[107]

September 11 terrorist attacks

Donald Rumsfeld and Giuliani at the site of the World Trade Center on November 14, 2001

Response

Giuliani was prominent in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. He made frequent appearances on radio and television on September 11 and afterwards—for example, to indicate that tunnels would be closed as a precautionary measure, and that there was no reason to believe that the dispersion of chemical or biological weaponry into the air was a factor in the attack. In his public statements, Giuliani said:

Tomorrow New York is going to be here. And we're going to rebuild, and we're going to be stronger than we were before... I want the people of New York to be an example to the rest of the country, and the rest of the world, that terrorism can't stop us.[108]

The 9/11 attacks occurred on the scheduled date of the mayoral primary to select the Democratic and Republican candidates to succeed Giuliani. The primary was immediately delayed two weeks to September 25. During this period, Giuliani sought an unprecedented three-month emergency extension of his term from January 1 to April 1 under the New York State Constitution (Article 3 Section 25).[109] He threatened to challenge the law imposing term limits on elected city officials and run for another full four-year term, if the primary candidates did not consent to the extension of his mayoralty.[110] In the end leaders in the State Assembly and Senate indicated that they did not believe the extension was necessary. The election proceeded as scheduled, and the winning candidate, the Giuliani-endorsed Republican convert Michael Bloomberg, took office on January 1, 2002 per normal custom.

Giuliani claimed to have been at the Ground Zero site "as often, if not more, than most workers... I was there working with them. I was exposed to exactly the same things they were exposed to. So in that sense, I'm one of them." Some 9/11 workers have objected to those claims.[111][112][113] While his appointment logs were unavailable for the six days immediately following the attacks, Giuliani logged 29 hours at the site over three months beginning September 17. This contrasted with recovery workers at the site who spent this much time at the site in two to three days.[114]

Giuliani at a NYFPC briefing after 9/11

When Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal suggested that the attacks were an indication that the United States "should re-examine its policies in the Middle East and adopt a more balanced stand toward the Palestinian cause", Giuliani asserted, "There is no moral equivalent for this act. There is no justification for it... And one of the reasons I think this happened is because people were engaged in moral equivalency in not understanding the difference between liberal democracies like the United States, like Israel, and terrorist states and those who condone terrorism. So I think not only are those statements wrong, they're part of the problem." Giuliani subsequently rejected the prince's $10 million donation to disaster relief in the aftermath of the attack.[115]

Communication preparedness

Giuliani has been widely criticized for his decision to locate the Office of Emergency Management headquarters on the 23rd floor inside the 7 World Trade Center building. Those opposing the decision perceived the office as a target for a terrorist attack in light of the previous terrorist attack against the World Trade Center in 1993.[116][117][118] The office was unable to coordinate efforts between police and firefighters properly while evacuating its headquarters.[119] Large tanks of diesel fuel were placed in 7 World Trade to power the command center. In May 1997, Giuliani put responsibility for selecting the location on Jerome M. Hauer, who had served under Giuliani from 1996 to 2000 before being appointed by him as New York City's first Director of Emergency Management. Hauer has taken exception to that account in interviews and provided Fox News and New York Magazine with a memo demonstrating that he recommended a location in Brooklyn but was overruled by Giuliani. Television journalist Chris Wallace interviewed Giuliani on May 13, 2007, about his 1997 decision to locate the command center at the World Trade Center. Giuliani laughed during Wallace's questions and said that Hauer recommended the World Trade Center site and claimed that Hauer said that the WTC site was the best location. Wallace presented Giuliani a photocopy of Hauer's directive letter. The letter urged Giuliani to locate the command center in Brooklyn, instead of lower Manhattan.[120][121][122][123][124] The February 1996 memo read, "The [Brooklyn] building is secure and not as visible a target as buildings in Lower Manhattan."[125]

Giuliani at a joint session of Congress on September 20, 2001, in which President Bush praised his efforts as Mayor and named Tom Ridge to a new cabinet-level position to oversee homeland defense initiatives

In January 2008, an eight-page memo was revealed which detailed the New York City Police Department's opposition in 1998 to location of the city's emergency command center at the Trade Center site. The Giuliani administration overrode these concerns.[126]

The 9/11 Commission Report noted that lack of preparedness could have led to the deaths of first responders at the scene of the attacks. The Commission noted that the radios in use by the fire department were the same radios which had been criticized for their ineffectiveness following the 1993 World Trade Center bombings. Family members of 9/11 victims have said that these radios were a complaint of emergency services responders for years.[127] The radios were not working when Fire Department chiefs ordered the 343 firefighters inside the towers to evacuate, and they remained in the towers as the towers collapsed.[128][129] However, when Giuliani testified before the 9/11 Commission he said that the firefighters ignored the evacuation order out of an effort to save lives.[130][131] Giuliani testified to the Commission, where some family members of responders who had died in the attacks appeared to protest his statements.[132] A 1994 mayoral office study of the radios indicated that they were faulty. Replacement radios were purchased in a $33 million no-bid contract with Motorola, and implemented in early 2001. However, the radios were recalled in March 2001 after a probationary firefighter's calls for help at a house fire could not be picked up by others at the scene, leaving firemen with the old analog radios from 1993.[128][133] A book later published by Commission members Thomas Kean and Lee H. Hamilton, Without Precedent: The Inside Story of the 9/11 Commission, argued that the Commission had not pursued a tough enough line of questioning with Giuliani.[134]

An October 2001 study by the National Institute of Environmental Safety and Health said that cleanup workers lacked adequate protective gear.[117][135]

Public reaction

Giuliani gained international attention in the wake of the attacks and was widely hailed for his leadership role during the crisis.[136]

Polls taken just six weeks after the attack showed that Giuliani received a 79 percent approval rating among New York City voters. This was a dramatic increase over the 36 percent rating he had received a year earlier, which was an average at the end of a two-term mayorship.[137][138]Oprah Winfrey called him "America's Mayor" at a 9/11 memorial service held at Yankee Stadium on September 23, 2001.[139][140] Other voices denied it was the mayor who had pulled the city together. "You didn't bring us together, our pain brought us together and our decency brought us together. We would have come together if Bozo was the mayor", said civil rights activist Al Sharpton, in a statement largely supported by Fernando Ferrer, one of three main candidates for the mayoralty at the end of 2001. "He was a power-hungry person", Sharpton also said.[141]

Giuliani was praised by some for his close involvement with the rescue and recovery efforts, but others argue that "Giuliani has exaggerated the role he played after the terrorist attacks, casting himself as a hero for political gain."[142] Giuliani has collected $11.4 million from speaking fees in a single year (with increased demand after the attacks).[143] Before September 11, Giuliani's assets were estimated to be somewhat less than $2 million, but his net worth could now be as high as 30 times that amount.[144] He has made most of his money since leaving office.[145]

Time Person of the Year

On December 24, 2001,[146]Time magazine named Giuliani its Person of the Year for 2001.[108]Time observed that, before 9/11, the public image of Giuliani had been that of a rigid, self-righteous, ambitious politician. After 9/11, and perhaps owing also to his bout with prostate cancer, his public image had been reformed to that of a man who could be counted on to unite a city in the midst of its greatest crisis. Historian Vincent J. Cannato concluded in September 2006:

With time, Giuliani's legacy will be based on more than just 9/11. He left a city immeasurably better off—safer, more prosperous, more confident—than the one he had inherited eight years earlier, even with the smoldering ruins of the World Trade Center at its heart. Debates about his accomplishments will continue, but the significance of his mayoralty is hard to deny.[147]

Aftermath

Thomas Von Essen and Giuliani at the New York Foreign Press Center Briefing on "New York City After September 11, 2001"

For his leadership on and after September 11, Giuliani was given an honorary knighthood (KBE) by Queen Elizabeth II on February 13, 2002.[148]

Giuliani initially downplayed the health effects arising from the September 11 attacks in the Financial District and lower Manhattan areas in the vicinity of the World Trade Center site.[149] He moved quickly to reopen Wall Street, and it was reopened on September 17. In the first month after the attacks, he said "The air quality is safe and acceptable."[150] However, in the weeks after the attacks, the United States Geological Survey identified hundreds of asbestos 'hot spots' of debris dust that remained on buildings. By the end of the month the USGS reported that the toxicity of the debris was akin to that of drain cleaner.[151] It would eventually be determined that a wide swath of lower Manhattan and Brooklyn had been heavily contaminated by highly caustic and toxic materials.[151][152] The city's health agencies, such as the Department of Environmental Protection, did not supervise or issue guidelines for the testing and cleanup of private buildings. Instead, the city left this responsibility to building owners.[151]

Giuliani and Secretary of State Colin Powell at the U.S. Delegation to OSCE's Anti-Semitism Meeting in Vienna, Austria, in 2003

Giuliani took control away from agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, leaving the "largely unknown" city Department of Design and Construction in charge of recovery and cleanup. Documents indicate that the Giuliani administration never enforced federal requirements requiring the wearing of respirators. Concurrently, the administration threatened companies with dismissal if cleanup work slowed.[153][154] In June 2007, Christie Todd Whitman, former Republican Governor of New Jersey and director of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), reportedly stated that the EPA had pushed for workers at the WTC site to wear respirators but that she had been blocked by Giuliani. She stated that she believed that the subsequent lung disease and deaths suffered by WTC responders were a result of these actions.[155] However, former deputy mayor Joe Lhota, then with the Giuliani campaign, replied, "All workers at Ground Zero were instructed repeatedly to wear their respirators."[156]

Giuliani asked the city's Congressional delegation to limit the city's liability for Ground Zero illnesses to a total of $350 million. Two years after Giuliani finished his term, FEMA appropriated $1 billion to a special insurance fund, called the World Trade Center Captive Insurance Company, to protect the city against 9/11 lawsuits.[157]

In February 2007, the International Association of Fire Fighters issued a letter asserting that Giuliani rushed to conclude the recovery effort once gold and silver had been recovered from World Trade Center vaults and thereby prevented the remains of many victims from being recovered: "Mayor Giuliani's actions meant that fire fighters and citizens who perished would either remain buried at Ground Zero forever, with no closure for families, or be removed like garbage and deposited at the Fresh Kills Landfill", it said, adding: "Hundreds remained entombed in Ground Zero when Giuliani gave up on them."[158] Lawyers for the International Association of Fire Fighters seek to interview Giuliani under oath as part of a federal legal action alleging that New York City negligently dumped body parts and other human remains in the Fresh Kills Landfill.[159]

Post-mayoralty

Politics

Before 2008 election

Giuliani and President Bush in Las Cruces, New Mexico, on August 26, 2004

Since leaving office as Mayor, Giuliani has remained politically active by campaigning for Republican candidates for political offices at all levels. When George Pataki became Governor in 1995, this represented the first time the positions of both Mayor and Governor of New York were held simultaneously by Republicans since Nelson Rockefeller and John Lindsay. Giuliani and Pataki were instrumental in bringing the 2004 Republican National Convention to New York City.[160] He was a speaker at the convention, and endorsed President George W. Bush for re-election by recalling that immediately after the World Trade Center towers fell,

Without really thinking, based on just emotion, spontaneous, I grabbed the arm of then-Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik, and I said to him, 'Bernie, thank God George Bush is our president'.[161]

Similarly, in June 2006, Giuliani started a website called Solutions America to help elect Republican candidates across the nation.

After campaigning on Bush's behalf in the U.S. presidential election of 2004, he was reportedly the top choice for Secretary of Homeland Security after Tom Ridge's resignation. When suggestions were made that Giuliani's confirmation hearings would be marred by details of his past affairs and scandals, he turned down the offer and instead recommended his friend and former New York Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik. After the formal announcement of Kerik's nomination, information about Kerik's past—most notably, that he had ties to organized crime, failed to properly report gifts he had received, had been sued for sexual harassment and had employed an undocumented alien as a domestic servant—became known, and Kerik withdrew his nomination.[162]

Giuliani cutting the ribbon of the new Drug Enforcement Administration mobile museum in Dallas, Texas, in September 2003

On March 15, 2006, Congress formed the Iraq Study Group (ISG). This bipartisan ten-person panel, of which Giuliani was one of the members, was charged with assessing the Iraq War and making recommendations. They would eventually unanimously conclude that contrary to Bush administration assertions, "The situation in Iraq is grave and deteriorating" and called for "changes in the primary mission" that would allow "the United States to begin to move its forces out of Iraq".[163]

On May 24, 2006, after missing all of the group's meetings,[164] including a briefing from General David Petraeus, former Secretary of State Colin Powell and former Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki,[165] Giuliani resigned from the panel, citing "previous time commitments".[166] Giuliani's fundraising schedule had kept him from participating in the panel, a schedule which raised $11.4 million in speaking fees over 14 months,[164] and that Giuliani had been forced to resign after being given "an ultimatum to either show up for meetings or leave the group" by group leader James Baker.[167] Giuliani subsequently said that he had started thinking about running for President, and being on the panel might give it a political spin.[168]

Giuliani was described by Newsweek in January 2007 as "one of the most consistent cheerleaders for the president's handling of the war in Iraq"[169] and as of June 2007, he remained one of the few candidates for president to unequivocally support both the basis for the invasion and the execution of the war.[170]

Giuliani spoke in support of the removal of the People's Mujahedin of Iran (MEK, also PMOI, MKO) from the United States State Department list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations. The group was on the State Department list from 1997 until September 2012. They were placed on the list for killing six Americans in Iran during the 1970s and attempting to attack the Iranian mission to the United Nations in 1992.[171][172] Giuliani, along with other former government officials and politicians Ed Rendell, R. James Woolsey, Porter Goss, Louis Freeh, Michael Mukasey, James L. Jones, Tom Ridge, and Howard Dean, were criticized for their involvement with the group. Some were subpoenaed during an inquiry about who was paying the prominent individuals' speaking fees.[173] Giuliani and others wrote an article for the conservative publication National Review stating their position that the group should not be classified as a terrorist organization. They supported their position by pointing out that the United Kingdom and the European Union had already removed the group from their terrorism lists. They further assert that only the United States and Iran still listed it as a terrorist group.[174] However, Canada did not delist the group until December 2012.[175]

2008 presidential campaign

Presidential campaign logo

In November 2006 Giuliani announced the formation of an exploratory committee toward a run for the presidency in 2008. In February 2007 he filed a "statement of candidacy" and confirmed on the television program Larry King Live that he was indeed running.[176]

Giuliani at a rally at San Diego State University in August 2007 when polls showed him as the front-runner for the Republican party's nomination

Early polls showed Giuliani with one of the highest levels of name recognition and support among the Republican candidates. Throughout most of 2007 he was the leader in most nationwide opinion polling among Republicans. Senator John McCain, who ranked a close second behind the New York Mayor, had faded, and most polls showed Giuliani to have more support than any of the other declared Republican candidates, with only former Senator Fred Thompson and former Governor Mitt Romney showing greater support in some per-state Republican polls.[177] On November 7, 2007, Giuliani's campaign received an endorsement from evangelist, Christian Broadcasting Network founder, and past presidential candidate Pat Robertson.[178] This was viewed by political observers as a possibly key development in the race, as it gave credence that evangelicals and other social conservatives could support Giuliani despite some of his positions on social issues such as abortion and gay rights.[179]

Giuliani's campaign hit a difficult stretch during the last two months of 2007, when Bernard Kerik, whom Giuliani had recommended for the position of Secretary of Homeland Security, was indicted on 16 counts of tax fraud and other federal charges.[180] The media reported that when Giuliani was the mayor of New York, he billed several tens of thousands of dollars of mayoral security expenses to obscure city agencies. Those expenses were incurred while he visited Judith Nathan, with whom he was having an extramarital affair[181] (later analysis showed the billing to likely be unrelated to hiding Nathan).[182] Several stories were published in the press regarding clients of Giuliani Partners and Bracewell & Giuliani who were in opposition to goals of American foreign policy.[183] Giuliani's national poll numbers began steadily slipping and his unusual strategy of focusing more on later, multi-primary big states rather than the smaller, first-voting states was seen at risk.[184][185]

Giuliani at a campaign event in Derry, New Hampshire, the day before the New Hampshire primary

Despite his strategy, Giuliani competed to a substantial extent[186] in the January 8, 2008 New Hampshire primary but finished a distant fourth with 9 percent of the vote.[187] Similar poor results continued in other early contests, when Giuliani's staff went without pay in order to focus all efforts on the crucial late January Florida Republican primary.[188] The shift of the electorate's focus from national security to the state of the economy also hurt Giuliani,[185] as did the resurgence of McCain's similarly themed campaign. On January 29, 2008, Giuliani finished a distant third in the Florida result with 15 percent of the vote, trailing McCain and Romney.[189] Facing declining polls and lost leads in the upcoming large Super Tuesday states,[190][191] including that of his home New York,[192] Giuliani withdrew from the race on January 30, endorsing McCain.[193]

Giuliani's campaign ended up $3.6 million in arrears,[194] and in June 2008 Giuliani sought to retire the debt by proposing to appear at Republican fundraisers during the 2008 general election, and have part of the proceeds go towards his campaign.[194] During the 2008 Republican National Convention, Giuliani gave a prime-time speech that praised McCain and his running mate, Sarah Palin, while criticizing Democratic nominee Barack Obama. He cited Palin's executive experience as a mayor and governor and belittled Obama's lack of same, and his remarks were met with wild applause from the delegates.[195] Giuliani continued to be one of McCain's most active surrogates during the remainder of McCain's eventually unsuccessful campaign.[196]

After 2008 election

Following the end of his presidential campaign, Giuliani's "high appearance fees dropped like a stone."[197] He returned to work at both Giuliani Partners and Bracewell & Giuliani.[198] Giuliani explored hosting a syndicated radio show, and was reported to be in talks with Westwood One about replacing Bill O'Reilly before that position went to Fred Thompson (another unsuccessful '08 GOP Presidential primary candidate).[199][200] During the March 2009 AIG bonus payments controversy, Giuliani called for U.S. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner to step down and said that the Obama administration lacked executive competence in dealing with the ongoing financial crisis.[201]

Giuliani gives the keynote speech at the Jumeriah Essex House in honor of the USS New York sailors and Special Purpose Marine Air Ground Task Force 26 Marines on November 8, 2009

Giuliani said his political career was not necessarily over, and did not rule out a 2010 New York gubernatorial or 2012 presidential bid.[202] A November 2008 Siena College poll indicated that although Governor David Paterson—promoted to the office via the Eliot Spitzer prostitution scandal a year before—was popular among New Yorkers, he would have just a slight lead over Giuliani in a hypothetical matchup.[203] By February 2009, after the prolonged Senate appointment process, a Siena College poll indicated that Paterson was losing popularity among New Yorkers, and showed Giuliani with a fifteen-point lead in the hypothetical contest.[204] In January 2009, Giuliani said he would not decide on a gubernatorial run for another six to eight months, adding that he thought it would not be fair to the governor to start campaigning early while the governor tries to focus on his job.[205] Giuliani worked to retire his presidential campaign debt, but by the end of March 2009 it was still $2.4 million in arrears, the largest such remaining amount for any of the 2008 contenders.[206] In April 2009, Giuliani strongly opposed Paterson's announced push for same-sex marriage in New York and said it would likely cause a backlash that could put Republicans in statewide office in 2010.[207] By late August 2009, there were still conflicting reports about whether Giuliani was likely to run.[208]

On December 23, 2009, Giuliani announced that he would not seek any office in 2010, saying "The main reason has to do with my two enterprises: Bracewell & Giuliani and Giuliani Partners. I'm very busy in both."[209][210] The decisions signaled a possible end to Giuliani's political career.[210][211] During the 2010 midterm elections, Giuliani endorsed and campaigned for Bob Ehrlich and Marco Rubio.[212][213]

On October 11, 2011, Giuliani announced that he was not running for president. According to Kevin Law, the Director of the Long Island Association, Giuliani believed that "As a moderate, he thought it was a pretty significant challenge. He said it's tough to be a moderate and succeed in GOP primaries", Giuliani said "If it's too late for (New Jersey Governor) Chris Christie, it's too late for me".[214]

At a Republican fund-raising event in February 2015, Giuliani stated, "I do not believe, and I know this is a horrible thing to say, but I do not believe that the president [Barack Obama] loves America", and "He doesn't love you. And he doesn't love me. He wasn't brought up the way you were brought up and I was brought up, through love of this country."[215] In response to criticism of the remarks, Giuliani said, "Some people thought it was racist—I thought that was a joke, since he was brought up by a white mother... This isn't racism. This is socialism or possibly anti-colonialism." White House deputy press secretary Eric Schultz said he agreed with Giuliani "that it was a horrible thing to say", but said he would leave it up to the people who heard Giuliani directly to assess if the remarks were appropriate for the event.[215] Although he received some support for his controversial comments, Giuliani said he also received several death threats within 48 hours.[216]

Relationship with Donald Trump

Giuliani speaking at a campaign event for Republican Presidential nominee Donald Trump on August 31, 2016

Presidential campaign supporter

Giuliani supported Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. He gave a prime time speech during the first night of the 2016 Republican National Convention.[217] Earlier in the day, Giuliani and former 2016 presidential candidate Ben Carson appeared at an event for the pro-Trump Great America PAC.[218] Giuliani also appeared in a Great America PAC ad entitled "Leadership".[219] Giuliani's and Jeff Sessions's appearances were staples at Trump campaign rallies.[220] During the campaign, Giuliani praised Trump for his worldwide accomplishments and helping fellow New Yorkers in their time of need.[221] He defended Trump against allegations of racism,[222]sexual assault,[223] and not paying any federal income taxes for as long as two decades.[224]

In August 2016, Giuliani, while campaigning for Trump, claimed that in the "eight years before Obama" became President, "we didn't have any successful radical Islamic terrorist attack in the United States." On the contrary, the terrorist attacks that took place on September 11, 2001 happened during the first term of the George W. Bush administration, which was eight years prior to Obama's Presidency. Politifact brought up four more counterexamples (the 2002 Los Angeles International Airport shooting, the 2002 D.C. sniper attacks, the 2006 Seattle Jewish Federation shooting and the 2006 UNC SUV attack) to Giuliani's claim. Giuliani later said he was using "abbreviated language".[225][226][227]

Giuliani was believed to be a likely pick for Secretary of State in the Trump administration.[228] However, on December 9, 2016, Trump announced that Giuliani had removed his name from consideration for any Cabinet post.[229]

Advisor to the President

On January 12, 2017, President-elect Trump named Giuliani his informal cybersecurity adviser.[230]

In January 2017, Giuliani said that he advised U.S. President Donald Trump in matters relating to Executive Order 13769, which barred citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the United States for 90 days. The order also suspended the admission of all refugees for 120 days.[231]

Giuliani has drawn scrutiny over his ties to foreign nations, regarding not registering per the Foreign Agents Registration Act.[232]

Personal lawyer

In mid April 2018, Giuliani joined President Trump's legal team, which dealt with the special counsel investigation by Robert Mueller into Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. elections. Giuliani said that his goal was to negotiate a swift end to the investigation.[233]

In early May, Giuliani made public that Trump had reimbursed his personal attorney Michael Cohen $130,000 that Cohen had paid to adult-film actress Stormy Daniels for her agreement not to talk about her alleged affair with Trump.[234] Cohen had earlier insisted that he used his own money to pay Daniels, and he implied that he had not been reimbursed.[235] Trump had previously said that he knew nothing about the matter.[236] Within a week, Giuliani said that some of his own statements regarding this matter were "more rumor than anything else".[237]

Later in May 2018, Giuliani, who was asked on whether the promotion of the Spygate conspiracy theory is meant to discredit the special counsel investigation, said that the investigators "are giving us the material to do it. Of course, we have to do it in defending the president ... it is for public opinion" on whether to "impeach or not impeach" Trump.[238] In June 2018, Giuliani claimed that a sitting president cannot be indicted: "I don't know how you can indict while he's in office. No matter what it is. ... If [President Trump] shot [then-FBI director] James Comey, he'd be impeached the next day. ... Impeach him, and then you can do whatever you want to do to him."[239]

In June 2018, Giuliani also said that President Trump should not testify to the special counsel investigation because "our recollection keeps changing".[240] In early July, Giuliani characterized that Trump had previously asked Comey to "give [then-national security adviser Michael Flynn] a break". In mid-August, Giuliani denied making this comment: "What I said was, that is what Comey is saying Trump said."[241] In late August, Giuliani argued that Trump should not testify to the special counsel investigation because Trump could be "trapped into perjury" just by telling "somebody's version of the truth. Not the truth." Giuliani's argument continued: "Truth isn't truth." Giuliani later clarified that he was "referring to the situation where two people make precisely contradictory statements".[242]

In late July, Giuliani defended Trump by stating that "collusion is not a crime", and that Trump did nothing wrong because Trump "didn’t hack" or "pay for the hacking" on the Democratic National Committee.[243]

Giuliani later elaborated that his comments were a "very, very familiar lawyer's argument" to "attack the legitimacy of the [special counsel] investigation".[244] He also described and denied several supposed allegations that have never been publicly raised, regarding two earlier meetings among Trump campaign officials to set up the June 9, 2016 Trump Tower meeting with Russian citizens.[245][246][247][248] In late August, Giuliani said that the June 9, 2016 Trump Tower "meeting was originally for the purpose of getting information about [Hillary] Clinton".[249]

Additionally in late July, Giuliani attacked Trump's former personal lawyer Michael Cohen as an "incredible liar", two months after calling Cohen an "honest, honorable lawyer."[250] In mid-August, Giuliani defended Trump by saying: "The president's an honest man."[251]

It was reported in early September that Giuliani said that the White House could and likely would prevent the special counsel investigation from making public certain information in its final report which would be covered by executive privilege. Also according to Giuliani, Trump's personal legal team is already preparing a "counter-report" to refute the potential special counsel investigation's report.[252]

Giuliani Partners

After leaving the mayor's office, Giuliani founded a security consulting business, Giuliani Partners LLC, in 2002, a firm that has been categorized by various media outlets as a lobbying entity capitalizing on Giuliani's name recognition,[253][254] and which has been the subject of allegations surrounding staff hired by Giuliani and due to the firm's chosen client base.[255] Over five years, Giuliani Partners earned more than $100 million.[256]

In June 2007 he stepped down as CEO and Chairman of Giuliani Partners,[183] although this action was not made public until December 4, 2007;[257] he maintained his equity interest in the firm.[183] Giuliani subsequently returned to active participation in the firm following the election. In late 2009, Giuliani announced that they had a security consulting contract with Rio de Janeiro, Brazil regarding the 2016 Summer Olympics.[211] He faced criticism in 2012 for advising people once allied with Slobodan Milošević who had lauded Serbian war criminals.[258]

Serbian President Tomislav Nikolić and Giuliani at a joint press conference, 2012

Bracewell & Giuliani

In 2005, Giuliani joined the law firm of Bracewell & Patterson LLP (renamed Bracewell & Giuliani LLP) as a name partner and basis for the expanding firm's new New York office.[259] When he joined the Texas-based firm he brought Marc Mukasey, the son of Attorney General Michael Mukasey, into the firm.

Despite a busy schedule, Giuliani was highly active in the day-to-day business of the law firm, which was a high-profile supplier of legal and lobbying services to the oil, gas, and energy industries. Its aggressive defense of pollution-causing coal-fired power plants threatened to cause political risk for Giuliani, but association with the firm helped Giuliani achieve fund-raising success in Texas.[260] In 2006, Giuliani acted as the lead counsel and lead spokesmen for Bracewell & Giuliani client Purdue Pharma, the makers of OxyContin, during their negotiations with federal prosecutors over charges that the pharmaceutical company misled the public about OxyContin's addictive properties. The agreement reached resulted in Purdue Pharma and some of its executives paying $634.5 million in fines.[261]

Bracewell & Giuliani represented corporate clients before many U.S. Government departments and agencies. Some clients have worked with corporations and foreign governments.[262]

Giuliani left the firm in January 2016,[263] by "amicable agreement,"[264] and the firm was rebranded as Bracewell LLP.

Greenberg Traurig

In January 2016, Giuliani moved to the law firm Greenberg Traurig, where he served as the global chairman for Greenberg's cybersecurity and crisis management group, as well as a senior advisor to the firm's executive chairman.[265] In April 2018, he took an unpaid leave of absence when he joined Trump's legal defense team.[266] He resigned from the firm on May 9, 2018.[267]

Other lobbying

In August 2018, Giuliani was retained by Freeh Group International Solutions, a global consulting firm run by former FBI Director Louis Freeh, which paid him a fee to lobby Romanian President Klaus Iohannis to change Romania's anti-corruption policy and reduce the role of the National Anticorruption Directorate.[268][269]

Personal life

Marriages and relationships

Congressman Vito Fossella, First Lady Nancy Reagan, and Giuliani, 2002

On October 26, 1968, Giuliani married his second cousin, Regina Peruggi, whom he had known since childhood. By the mid-1970s, the marriage was in trouble and they agreed to a trial separation in 1975.[270] Peruggi did not accompany him to Washington when he accepted the job in the Attorney General's Office.[24]

Giuliani met local television personality Donna Hanover sometime in 1982, and they began dating when she was working in Miami. Giuliani filed for legal separation from Peruggi on August 12, 1982.[270] The Giuliani-Peruggi marriage legally ended in two ways: a civil divorce was issued by the end of 1982,[271] while a Roman Catholic church annulment of the Giuliani-Peruggi marriage was granted at the end of 1983[270] reportedly because Giuliani had discovered that he and Peruggi were second cousins.[272][273] Giuliani biographer Wayne Barrett reports that Peruggi's brother believes that Giuliani knew at the time of the marriage that they were second cousins. Alan Placa, Giuliani's best man, later became a priest and helped get the annulment. Giuliani and Peruggi did not have any children.[274]

Giuliani and Hanover then married in a Catholic ceremony at St. Monica's Church in Manhattan on April 15, 1984.[270][275] They had two children, son Andrew and daughter Caroline.

In 1996, Donna Hanover reverted to her professional name and virtually stopped appearing in public with her husband.[276] By 1995, there were rumors that Giuliani was having an affair with his press secretary, Cristyne Lategano. On Father's Day of that year Giuliani had told reporters that he was returning to Gracie Mansion to play ball with his son but instead took Lategano to a basement suite in City Hall. Three hours later Hanover went to City Hall to confront Giuliani, but a mayor's aide prevented her from entering the suite.[277]

A New York Air National Guard major poses with Rudy and Judith Giuliani at Yankee Stadium in April 2009

Giuliani was still married to Hanover in May 1999 when he met Judith Nathan—a sales manager for a pharmaceutical company—at Club Macanudo, an Upper East Side cigar bar.[278] They formed an ongoing relationship.[278][279] In summer 1999, Giuliani charged the costs for his NYPD security detail to obscure city agencies in order to keep his relationship with Nathan from public scrutiny.[181][280] In early 2000, the police department began providing Nathan with city-provided chauffeur services.[280]

By March 2000, Giuliani had stopped wearing his wedding ring.[281] The appearances that he and Nathan made at functions and events became publicly visible,[281][282] although the appearances were not mentioned in the press.[283] In early May 2000, the Daily News and the New York Post both broke news of Giuliani's relationship with Nathan.[283] Giuliani first publicly acknowledged her on May 3, 2000, when he stated that Nathan was his "very good friend".[281]

On May 10, 2000, Giuliani called a press conference to announce that he intended to separate from Hanover.[284][285] Giuliani had not informed Hanover about his plans before his press conference.[286] This was an omission for which Giuliani was widely criticized.[287] Giuliani now went on to praise Nathan as a "very, very fine woman", and said about Hanover that "over the course of some period of time in many ways, we've grown to live independent and separate lives". Hours later Hanover said, "I had hoped that we could keep this marriage together. For several years, it was difficult to participate in Rudy's public life because of his relationship with one staff member".[288]

Giuliani moved out of Gracie Mansion by August 2001 and into the apartment of a gay friend and his life partner.[289][290] Giuliani filed for divorce from Hanover in October 2000,[291] and a public battle broke out between their representatives.[292] Nathan was barred by court order from entering Gracie Mansion or meeting his children before the divorce was final.[293]

In May 2001, Giuliani's attorney revealed that Giuliani was impotent due to prostate cancer treatments and had not had sex with Nathan for the preceding year. "You don't get through treatment for cancer and radiation all by yourself", Giuliani said. "You need people to help you and care for you and support you. And I'm very fortunate I had a lot of people who did that, but nobody did more to help me than Judith Nathan."[294] In a court case, Giuliani argued that he planned to introduce Nathan to his children on Father's Day 2001 and that Hanover had prevented this visit.[277] Giuliani and Hanover finally settled their divorce case in July 2002 after his mayoralty had ended, with Giuliani paying Hanover a $6.8 million settlement and granting her custody of their children.[295] Giuliani married Nathan on May 24, 2003, and gained a stepdaughter, Whitney. It was also Nathan's third marriage after two divorces.[288]

By March 2007, The New York Times and the Daily News reported that Giuliani had become estranged from both his son Andrew and his daughter Caroline.[296][297] In 2014, he said his relationship with his children was better than ever, and was spotted eating and playing golf with Andrew.[298]

On April 4, 2018, Nathan filed for divorce from Giuliani after 15 years of marriage.[299] Giuliani is currently dating Republican fundraiser Jennifer LeBlanc.[300][301]

Prostate cancer

In April 1981, Giuliani's father died at age 73 of prostate cancer at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center. Nineteen years later in April 2000, Giuliani was 55 when he was diagnosed with prostate cancer on prostate biopsy after an elevated screening PSA.[302] Giuliani chose a combination prostate cancer treatment consisting of four months of neoadjuvant Lupron hormonal therapy, then low dose-rate prostate brachytherapy with permanent implantation of ninety TheraSeed radioactive palladium-103 seeds in his prostate in September 2000,[303] followed two months later by five weeks of fifteen-minute, five-days-a-week external beam radiotherapy at Mount Sinai Medical Center,[304] with five months of adjuvant Lupron hormonal therapy.

Religion and beliefs

Giuliani has declined to comment publicly on his religious practice and beliefs, although he identifies religion as an important part of his life. When asked if he is a practicing Catholic, Giuliani answered, "My religious affiliation, my religious practices and the degree to which I am a good or not-so-good Catholic, I prefer to leave to the priests."[305]

Awards and honors

- In 1998, Giuliani received The Hundred Year Association of New York's Gold Medal Award "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York".[306]

House of Savoy: Knight Grand Cross (motu proprio) of the Order of Merit of Savoy (December 2001)[307]

House of Savoy: Knight Grand Cross (motu proprio) of the Order of Merit of Savoy (December 2001)[307]

- For his leadership on and after September 11, Giuliani was made an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II on February 13, 2002.[308]

- Giuliani was named Time magazine's "Person of the Year" for 2001

- In 2002, the Episcopal Diocese of New York gave Giuliani the Fiorello LaGuardia Public Service Award for Valor and Leadership in the Time of Global Crisis.[309]

- Also in 2002, Former First Lady Nancy Reagan awarded Giuliani the Ronald Reagan Freedom Award.[310]

- In 2002, he received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[311]

- In 2003, Giuliani received the Academy of Achievement's Golden Plate Award

- In 2004, construction began on the Rudolph W. Giuliani Trauma Center at St. Vincent's Hospital in New York.[312]

- In 2005, Giuliani received honorary degrees from Loyola College in Maryland[313] and Middlebury College.[314] In 2007, Giuliani received an honorary Doctorate in Public Administration from The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina.

- In 2006, Rudy and Judith Giuliani were honored by the American Heart Association at its annual Heart of the Hamptons benefit in Water Mill, New York.

- In 2007, Giuliani was honored by the National Italian American Foundation (NIAF), receiving the NIAF Special Achievement Award for Public Service.[315]

- In 2007, Giuliani was awarded the Margaret Thatcher Medal of Freedom by the Atlantic Bridge.[316]

- In the 2009 graduation ceremony for Drexel University's Earle Mack School of Law, Giuliani was the keynote speaker and recipient of an honorary degree.[317]

- Giuliani was the Robert C. Vance Distinguished Lecturer at Central Connecticut State University in 2013.[318]

Media references

- In 1993, Giuliani made a cameo appearance as himself in the Seinfeld episode "The Non-Fat Yogurt", which is a fictionalized account of the 1993 mayoral election. Giuliani's scenes were filmed the morning after his real world election.[319]

- In 2000, Giuliani made a cameo appearance in the Law & Order episode "Endurance".

- Biographical drama Rudy: The Rudy Giuliani Story (2003), in which he is played by James Woods.

- Kevin Keating's documentary Giuliani Time (2006).

- In 2003, Giuliani made a cameo appearance as himself in the film Anger Management, starring Adam Sandler and Jack Nicholson.

- In 2018, Giuliani was portrayed multiple times in Saturday Night Live by Kate McKinnon.[320]

See also

- Political positions of Rudy Giuliani

- Electoral history of Rudy Giuliani

- Public image of Rudy Giuliani

Timeline of New York City, 1990s–2000s

References

^ Phillip, Abby (January 12, 2017). "Trump names Rudy Giuliani as cybersecurity adviser". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 13, 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Nomination of Rudolph W. Giuliani To Be an Associate Attorney General

^ ab Gina M Robertiello, "Giuliani, Rudolph", pp. 687–99, in Wilbur R. Miller, ed, The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia (Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi, London: Sage Publications, 2012).

^ Elisabeth Bumiller (May 20, 2000). "The Mayor's decision: The overview; cancer is concern". New York Times.

^ "Person Of The Year 2001". Time.

^ Stephen M. Silverman, "Queen Elizabeth knights Rudy Giuliani – Queen Elizabeth II", People, February 13, 2002.

^ Cohen et al., "The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform," Chicago: 2008, p 338.

^ "Rudy Giuliani: Governor of New York in 2010?" Archived December 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine., Right Pundits, December 22, 2009.

^ "Giuliani says decision on governor's race unlikely before summer". CNN. January 13, 2009.

^ Walshe, Shushannah (March 17, 2011). "Rudy Giuliani Plays 2012 Flirt". Retrieved August 16, 2016.

^ "Rudy Giuliani 2010: Ex-Mayor announces that he won't run for office". Huffington Post. December 22, 2009.

^ Maggie Haberman, "Rudy Giuliani: I'm not running in 2012", Politico.com; accessed May 17, 2017.

^ Juliet Eilperin (February 8, 2012). "Rudy Giuliani doesn't regret sitting out 2012 race". Washington Post.

^ Costa, Robert; Dawsey, Josh (April 19, 2018). "Giuliani says he is joining Trump's legal team to 'negotiate an end' to Mueller probe". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

^ ab Burton, Danielle (February 7, 2007). "10 Things You Didn't Know About Rudy Giuliani". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on March 18, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2007.