Cryptocurrency

Various cryptocurrency logos. The bitcoin logo in the middle displays two hands, one hand is giving and one hand is receiving, as a metaphor for the exchanging of bitcoin.

A cryptocurrency (or crypto currency) is a digital asset designed to work as a medium of exchange that uses strong cryptography to secure financial transactions, control the creation of additional units, and verify the transfer of assets.[1][2][3] Cryptocurrencies are a kind of alternative currency and digital currency (of which virtual currency is a subset). Cryptocurrencies use decentralized control as opposed to centralized digital currency and central banking systems.[4]

The decentralized control of each cryptocurrency works through distributed ledger technology, typically a blockchain, that serves as a public financial transaction database.[5]

Bitcoin, first released as open-source software in 2009, is generally considered the first decentralized cryptocurrency.[6] Since the release of bitcoin, over 4,000 altcoins (alternative variants of bitcoin, or other cryptocurrencies) have been created.

Contents

1 History

2 Formal definition

2.1 Altcoin

2.2 Crypto token

3 Architecture

3.1 Blockchain

3.1.1 Timestamping

3.2 Mining

3.2.1 GPU price rise

3.3 Wallets

3.4 Anonymity

3.5 Fungibility

4 Economics

4.1 Transaction fees

4.2 Exchanges

4.3 Atomic swaps

4.4 ATMs

4.5 Initial coin offerings

5 Legality

5.1 Advertising bans

5.2 U.S. tax status

5.3 The legal concern of an unregulated global economy

5.4 Loss, theft, and fraud

5.5 Darknet markets

6 Reception

6.1 Academic studies

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

History

In 1983, the American cryptographer David Chaum conceived an anonymous cryptographic electronic money called ecash.[7][8] Later, in 1995, he implemented it through Digicash,[9] an early form of cryptographic electronic payments which required user software in order to withdraw notes from a bank and designate specific encrypted keys before it can be sent to a recipient. This allowed the digital currency to be untraceable by the issuing bank, the government, or any third party.

In 1996, the NSA published a paper entitled How to Make a Mint: the Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash, describing a Cryptocurrency system first publishing it in a MIT mailing list[10] and later in 1997, in The American Law Review (Vol. 46, Issue 4).[11]

In 1998, Wei Dai published a description of "b-money", characterized as an anonymous, distributed electronic cash system.[12] Shortly thereafter, Nick Szabo described bit gold.[13] Like bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies that would follow it, bit gold (not to be confused with the later gold-based exchange, BitGold) was described as an electronic currency system which required users to complete a proof of work function with solutions being cryptographically put together and published. A currency system based on a reusable proof of work was later created by Hal Finney who followed the work of Dai and Szabo.

The first decentralized cryptocurrency, bitcoin, was created in 2009 by pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto. It used SHA-256, a cryptographic hash function, as its proof-of-work scheme.[14][15] In April 2011, Namecoin was created as an attempt at forming a decentralized DNS, which would make internet censorship very difficult. Soon after, in October 2011, Litecoin was released. It was the first successful cryptocurrency to use scrypt as its hash function instead of SHA-256. Another notable cryptocurrency, Peercoin was the first to use a proof-of-work/proof-of-stake hybrid.[16]

On 6 August 2014, the UK announced its Treasury had been commissioned to do a study of cryptocurrencies, and what role, if any, they can play in the UK economy. The study was also to report on whether regulation should be considered.[17]

Formal definition

According to Jan Lansky, a cryptocurrency is a system that meets six conditions:[18]

- The system does not require a central authority, its state is maintained through distributed consensus.

- The system keeps an overview of cryptocurrency units and their ownership.

- The system defines whether new cryptocurrency units can be created. If new cryptocurrency units can be created, the system defines the circumstances of their origin and how to determine the ownership of these new units.

- Ownership of cryptocurrency units can be proved exclusively cryptographically.

- The system allows transactions to be performed in which ownership of the cryptographic units is changed. A transaction statement can only be issued by an entity proving the current ownership of these units.

- If two different instructions for changing the ownership of the same cryptographic units are simultaneously entered, the system performs at most one of them.

In March 2018, the word cryptocurrency was added to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.[19]

Altcoin

The term altcoin has various similar definitions. Stephanie Yang of The Wall Street Journal defined altcoins as "alternative digital currencies,"[20] while Paul Vigna, also of The Wall Street Journal, described altcoins as alternative versions of bitcoin.[21] Aaron Hankins of the MarketWatch refers to any cryptocurrencies other than bitcoin as altcoins.[22]

Crypto token

A blockchain account can provide functions other than making payments, for example in decentralized applications or smart contracts. In this case, the units or coins are sometimes referred to as crypto tokens (or cryptotokens).

Architecture

Decentralized cryptocurrency is produced by the entire cryptocurrency system collectively, at a rate which is defined when the system is created and which is publicly known. In centralized banking and economic systems such as the Federal Reserve System, corporate boards or governments control the supply of currency by printing units of fiat money or demanding additions to digital banking ledgers. In case of decentralized cryptocurrency, companies or governments cannot produce new units, and have not so far provided backing for other firms, banks or corporate entities which hold asset value measured in it. The underlying technical system upon which decentralized cryptocurrencies are based was created by the group or individual known as Satoshi Nakamoto.[23]

As of May 2018[update], over 1,800 cryptocurrency specifications existed.[24] Within a cryptocurrency system, the safety, integrity and balance of ledgers is maintained by a community of mutually distrustful parties referred to as miners: who use their computers to help validate and timestamp transactions, adding them to the ledger in accordance with a particular timestamping scheme.[14]

Most cryptocurrencies are designed to gradually decrease production of that currency, placing a cap on the total amount of that currency that will ever be in circulation.[25] Compared with ordinary currencies held by financial institutions or kept as cash on hand, cryptocurrencies can be more difficult for seizure by law enforcement.[1] This difficulty is derived from leveraging cryptographic technologies.

Blockchain

The validity of each cryptocurrency's coins is provided by a blockchain. A blockchain is a continuously growing list of records, called blocks, which are linked and secured using cryptography.[23][26] Each block typically contains a hash pointer as a link to a previous block,[26] a timestamp and transaction data.[27] By design, blockchains are inherently resistant to modification of the data. It is "an open, distributed ledger that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way".[28] For use as a distributed ledger, a blockchain is typically managed by a peer-to-peer network collectively adhering to a protocol for validating new blocks. Once recorded, the data in any given block cannot be altered retroactively without the alteration of all subsequent blocks, which requires collusion of the network majority.

Blockchains are secure by design and are an example of a distributed computing system with high Byzantine fault tolerance. Decentralized consensus has therefore been achieved with a blockchain.[29] Blockchains solve the double-spending problem without the need of a trusted authority or central server, assuming no 51% attack (that has worked against several cryptocurrencies).

Timestamping

Cryptocurrencies use various timestamping schemes to "prove" the validity of transactions added to the blockchain ledger without the need for a trusted third party.

The first timestamping scheme invented was the proof-of-work scheme. The most widely used proof-of-work schemes are based on SHA-256 and scrypt.[16]

Some other hashing algorithms that are used for proof-of-work include CryptoNight, Blake, SHA-3, and X11.

The proof-of-stake is a method of securing a cryptocurrency network and achieving distributed consensus through requesting users to show ownership of a certain amount of currency. It is different from proof-of-work systems that run difficult hashing algorithms to validate electronic transactions. The scheme is largely dependent on the coin, and there's currently no standard form of it. Some cryptocurrencies use a combined proof-of-work/proof-of-stake scheme.[16]

Mining

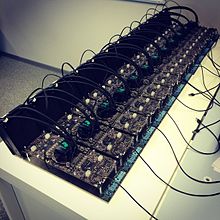

Hashcoin mine

In cryptocurrency networks, mining is a validation of transactions. For this effort, successful miners obtain new cryptocurrency as a reward. The reward decreases transaction fees by creating a complementary incentive to contribute to the processing power of the network. The rate of generating hashes, which validate any transaction, has been increased by the use of specialized machines such as FPGAs and ASICs running complex hashing algorithms like SHA-256 and Scrypt.[30] This arms race for cheaper-yet-efficient machines has been on since the day the first cryptocurrency, bitcoin, was introduced in 2009.[30] With more people venturing into the world of virtual currency, generating hashes for this validation has become far more complex over the years, with miners having to invest large sums of money on employing multiple high performance ASICs. Thus the value of the currency obtained for finding a hash often does not justify the amount of money spent on setting up the machines, the cooling facilities to overcome the enormous amount of heat they produce, and the electricity required to run them.[30][31]

Some miners pool resources, sharing their processing power over a network to split the reward equally, according to the amount of work they contributed to the probability of finding a block. A "share" is awarded to members of the mining pool who present a valid partial proof-of-work.

As of February 2018[update], the Chinese Government halted trading of virtual currency, banned initial coin offerings and shut down mining. Some Chinese miners have since relocated to Canada.[32] One company is operating data centers for mining operations at Canadian oil and gas field sites, due to low gas prices.[33] In June 2018, Hydro Quebec proposed to the provincial government to allocate 500 MW to crypto companies for mining.[34] According to a February 2018 report from Fortune,[35] Iceland has become a haven for cryptocurrency miners in part because of its cheap electricity. Prices are contained because nearly all of the country's energy comes from renewable sources, prompting more mining companies to consider opening operations in Iceland. The region's energy company says bitcoin mining is becoming so popular that the country will likely use more electricity to mine coins than power homes in 2018. In October 2018 Russia was to become home to one of the largest legal mining operations in the world, located in Siberia.[citation needed]

In March 2018, a town in Upstate New York put an 18-month moratorium on all cryptocurrency mining in an effort to preserve natural resources and the "character and direction" of the city.[36]

GPU price rise

An increase in cryptocurrency mining increased the demand of graphics cards (GPU) in 2017.[37] Popular favorites of cryptocurrency miners such as Nvidia's GTX 1060 and GTX 1070 graphics cards, as well as AMD's RX 570 and RX 580 GPUs, doubled or tripled in price – or were out of stock.[38] A GTX 1070 Ti which was released at a price of $450 sold for as much as $1100. Another popular card GTX 1060's 6 GB model was released at an MSRP of $250, sold for almost $500. RX 570 and RX 580 cards from AMD were out of stock for almost a year. Miners regularly buy up the entire stock of new GPU's as soon as they are available.[39]

Nvidia has asked retailers to do what they can when it comes to selling GPUs to gamers instead of miners. "Gamers come first for Nvidia," said Boris Böhles, PR manager for Nvidia in the German region.[40]

Wallets

An example paper printable bitcoin wallet consisting of one bitcoin address for receiving and the corresponding private key for spending

A cryptocurrency wallet stores the public and private "keys" or "addresses" which can be used to receive or spend the cryptocurrency. With the private key, it is possible to write in the public ledger, effectively spending the associated cryptocurrency. With the public key, it is possible for others to send currency to the wallet.

Anonymity

Bitcoin is pseudonymous rather than anonymous in that the cryptocurrency within a wallet is not tied to people, but rather to one or more specific keys (or "addresses").[41] Thereby, bitcoin owners are not identifiable, but all transactions are publicly available in the blockchain. Still, cryptocurrency exchanges are often required by law to collect the personal information of their users.

Additions such as Zerocoin, Zerocash and CryptoNote have been suggested, which would allow for additional anonymity and fungibility.[42][43]

Fungibility

Most cryptocurrency tokens are fungible and interchangeable. However, unique non-fungible tokens also exist. Such tokens can serve as assets in games like CryptoKitties.

Economics

Cryptocurrencies are used primarily outside existing banking and governmental institutions and are exchanged over the Internet.

Transaction fees

Transaction fees for cryptocurrency depend mainly on the supply of network capacity at the time, versus the demand from the currency holder for a faster transaction. The currency holder can choose a specific transaction fee, while network entities process transactions in order of highest offered fee to lowest. Cryptocurrency exchanges can simplify the process for currency holders by offering priority alternatives and thereby determine which fee will likely cause the transaction to be processed in the requested time.

For ether, transaction fees differ by computational complexity, bandwidth use, and storage needs, while bitcoin transaction fees differ by transaction size and whether the transaction uses SegWit. In September 2018, the median transaction fee for ether corresponded to $0.017,[44] while for bitcoin it corresponded to $0.55.[45]

Exchanges

Cryptocurrency exchanges allow customers to trade cryptocurrencies for other assets, such as conventional fiat money, or to trade between different digital currencies.

Atomic swaps

Atomic swaps are a mechanism where one cryptocurrency can be exchanged directly for another cryptocurrency, without the need for a trusted third party such as an exchange.

ATMs

Bitcoin ATM

Jordan Kelley, founder of Robocoin, launched the first bitcoin ATM in the United States on 20 February 2014. The kiosk installed in Austin, Texas is similar to bank ATMs but has scanners to read government-issued identification such as a driver's license or a passport to confirm users' identities.[46]

Initial coin offerings

An initial coin offering (ICO) is a controversial means of raising funds for a new cryptocurrency venture. An ICO may be used by startups with the intention of avoiding regulation. However, securities regulators in many jurisdictions, including in the U.S., and Canada have indicated that if a coin or token is an "investment contract" (e.g., under the Howey test, i.e., an investment of money with a reasonable expectation of profit based significantly on the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others), it is a security and is subject to securities regulation. In an ICO campaign, a percentage of the cryptocurrency (usually in the form of "tokens") is sold to early backers of the project in exchange for legal tender or other cryptocurrencies, often bitcoin or ether.[47][48][49]

According to PricewaterhouseCoopers, four of the 10 biggest proposed initial coin offerings have used Switzerland as a base, where they are frequently registered as non-profit foundations. The Swiss regulatory agency FINMA stated that it would take a "balanced approach" to ICO projects and would allow "legitimate innovators to navigate the regulatory landscape and so launch their projects in a way consistent with national laws protecting investors and the integrity of the financial system." In response to numerous requests by industry representatives, a legislative ICO working group began to issue legal guidelines in 2018, which are intended to remove uncertainty from cryptocurrency offerings and to establish sustainable business practices.[50]

Legality

The legal status of cryptocurrencies varies substantially from country to country and is still undefined or changing in many of them. While some countries have explicitly allowed their use and trade,[51] others have banned or restricted it. According to the Library of Congress, an "absolute ban" on trading or using cryptocurrencies applies in eight countries: Algeria, Bolivia, Egypt, Iraq, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. An "implicit ban" applies in another 15 countries, which include Bahrain, Bangladesh, China, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Indonesia, Iran, Kuwait, Lesotho, Lithuania, Macau, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Taiwan.[52] In the United States and Canada, state and provincial securities regulators, coordinated through the North American Securities Administrators Association, are investigating "bitcoin scams" and ICOs in 40 jurisdictions.[53]

Various government agencies, departments, and courts have classified bitcoin differently. China Central Bank banned the handling of bitcoins by financial institutions in China in early 2014.

In Russia, though cryptocurrencies are legal, it is illegal to actually purchase goods with any currency other than the Russian ruble.[54] Regulations and bans that apply to bitcoin probably extend to similar cryptocurrency systems.[55]

Cryptocurrencies are a potential tool to evade economic sanctions for example against Russia, Iran, or Venezuela. In April 2018, Russian and Iranian economic representatives met to discuss how to bypass the global SWIFT system through decentralized blockchain technology.[56] Russia also secretly supported Venezuela with the creation of the petro (El Petro), a national cryptocurrency initiated by the Maduro government to obtain valuable oil revenues by circumventing US sanctions.

In August 2018, the Bank of Thailand announced its plans to create its own cryptocurrency, the Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).[57]

Advertising bans

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency advertisements were temporarily banned on Facebook,[58]Google, Twitter,[59]Bing,[60]Snapchat, LinkedIn and MailChimp.[61] Chinese internet platforms Baidu, Tencent, and Weibo have also prohibited bitcoin advertisements. The Japanese platform Line and the Russian platform Yandex have similar prohibitions.[62]

U.S. tax status

On 25 March 2014, the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS) ruled that bitcoin will be treated as property for tax purposes. This means bitcoin will be subject to capital gains tax.[63]

In a paper published by researchers from Oxford and Warwick, it was shown that bitcoin has some characteristics more like the precious metals market than traditional currencies, hence in agreement with the IRS decision even if based on different reasons.[64]

The legal concern of an unregulated global economy

As the popularity of and demand for online currencies has increased since the inception of bitcoin in 2009,[65] so have concerns that such an unregulated person to person global economy that cryptocurrencies offer may become a threat to society. Concerns abound that altcoins may become tools for anonymous web criminals.[66]

Cryptocurrency networks display a lack of regulation that has been criticized as enabling criminals who seek to evade taxes and launder money.

Transactions that occur through the use and exchange of these altcoins are independent from formal banking systems, and therefore can make tax evasion simpler for individuals. Since charting taxable income is based upon what a recipient reports to the revenue service, it becomes extremely difficult to account for transactions made using existing cryptocurrencies, a mode of exchange that is complex and difficult to track.[66]

Systems of anonymity that most cryptocurrencies offer can also serve as a simpler means to launder money. Rather than laundering money through an intricate net of financial actors and offshore bank accounts, laundering money through altcoins can be achieved through anonymous transactions.[66]

Loss, theft, and fraud

In February 2014 the world's largest bitcoin exchange, Mt. Gox, declared bankruptcy. The company stated that it had lost nearly $473 million of their customers' bitcoins likely due to theft. This was equivalent to approximately 750,000 bitcoins, or about 7% of all the bitcoins in existence. The price of a bitcoin fell from a high of about $1,160 in December to under $400 in February.[67]

Two members of the Silk Road Task Force—a multi-agency federal task force that carried out the U.S. investigation of Silk Road—seized bitcoins for their own use in the course of the investigation.[68]DEA agent Carl Mark Force IV, who attempted to extort Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht ("Dread Pirate Roberts"), pleaded guilty to money laundering, obstruction of justice, and extortion under color of official right, and was sentenced to 6.5 years in federal prison.[68]U.S. Secret Service agent Shaun Bridges pleaded guilty to crimes relating to his diversion of $800,000 worth of bitcoins to his personal account during the investigation, and also separately pleaded guilty to money laundering in connection with another cryptocurrency theft; he was sentenced to nearly eight years in federal prison.[69]

Homero Josh Garza, who founded the cryptocurrency startups GAW Miners and ZenMiner in 2014, acknowledged in a plea agreement that the companies were part of a pyramid scheme, and pleaded guilty to wire fraud in 2015. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission separately brought a civil enforcement action against Garza, who was eventually ordered to pay a judgment of $9.1 million plus $700,000 in interest. The SEC's complaint stated that Garza, through his companies, had fraudulently sold "investment contracts representing shares in the profits they claimed would be generated" from mining.[70]

On 21 November 2017, the Tether cryptocurrency announced they were hacked, losing $31 million in USDT from their primary wallet.[71] The company has 'tagged' the stolen currency, hoping to 'lock' them in the hacker's wallet (making them unspendable). Tether indicates that it is building a new core for its primary wallet in response to the attack in order to prevent the stolen coins from being used.

In May 2018, Bitcoin Gold (and two other cryptocurrencies) were hit by a successful 51% hashing attack by an unknown actor, in which exchanges lost estimated $18m.[72] In June 2018, Korean exchange Coinrail was hacked, losing US$37 million worth of altcoin. Fear surrounding the hack was blamed for a $42 billion cryptocurrency market selloff.[73] On 9 July 2018 the exchange Bancor had $23.5 million in cryptocurrency stolen.[74]

The French regulator Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) lists 15 websites of companies that solicit investment in cryptocurrency without being authorised to do so in France.[75]

Darknet markets

Properties of cryptocurrencies gave them popularity in applications such as a safe haven in banking crises and means of payment, which also led to the cryptocurrency use in controversial settings in the form of online black markets, such as Silk Road.[66] The original Silk Road was shut down in October 2013 and there have been two more versions in use since then. In the year following the initial shutdown of Silk Road, the number of prominent dark markets increased from four to twelve, while the amount of drug listings increased from 18,000 to 32,000.[66]

Darknet markets present challenges in regard to legality. Bitcoins and other forms of cryptocurrency used in dark markets are not clearly or legally classified in almost all parts of the world. In the U.S., bitcoins are labelled as "virtual assets". This type of ambiguous classification puts pressure on law enforcement agencies around the world to adapt to the shifting drug trade of dark markets.[76]

Reception

Cryptocurrencies have been compared to Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes[77] and economic bubbles,[78] such as housing market bubbles.[79]Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital Management stated in 2017 that digital currencies were "nothing but an unfounded fad (or perhaps even a pyramid scheme), based on a willingness to ascribe value to something that has little or none beyond what people will pay for it", and compared them to the tulip mania (1637), South Sea Bubble (1720), and dot-com bubble (1999).[80]

While cryptocurrencies are digital currencies that are managed through advanced encryption techniques, many governments have taken a cautious approach toward them, fearing their lack of central control and the effects they could have on financial security.[81] Regulators in several countries have warned against cryptocurrency and some have taken concrete regulatory measures to dissuade users.[82] Additionally, many banks do not offer services for cryptocurrencies and can refuse to offer services to virtual-currency companies.[83] Gareth Murphy, a senior central banking officer has stated "widespread use [of cryptocurrency] would also make it more difficult for statistical agencies to gather data on economic activity, which are used by governments to steer the economy". He cautioned that virtual currencies pose a new challenge to central banks' control over the important functions of monetary and exchange rate policy.[84] While traditional financial products have strong consumer protections in place, there is no intermediary with the power to limit consumer losses if bitcoins are lost or stolen.[85] One of the features cryptocurrency lacks in comparison to credit cards, for example, is consumer protection against fraud, such as chargebacks.

An enormous amount of energy goes into proof-of-work cryptocurrency mining, although cryptocurrency proponents claim it is important to compare it to the consumption of the traditional financial system.[86]

There are also purely technical elements to consider. For example, technological advancement in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin result in high up-front costs to miners in the form of specialized hardware and software.[87] Cryptocurrency transactions are normally irreversible after a number of blocks confirm the transaction. Additionally, cryptocurrency private keys can be permanently lost from local storage due to malware, data loss or the destruction of the physical media. This prevents the cryptocurrency from being spent, resulting in its effective removal from the markets.[88]

The cryptocurrency community refers to pre-mining, hidden launches, ICO or extreme rewards for the altcoin founders as a deceptive practice.[89] It can also be used as an inherent part of a cryptocurrency's design.[90] Pre-mining means currency is generated by the currency's founders prior to being released to the public.[91]

Paul Krugman, Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences winner does not like bitcoin, has repeated numerous times that it is a bubble that will not last[92] and links it to Tulip mania.[93] American business magnate Warren Buffett thinks that cryptocurrency will come to a bad ending.[94] In October 2017, BlackRock CEO Laurence D. Fink called bitcoin an 'index of money laundering'.[95] "Bitcoin just shows you how much demand for money laundering there is in the world," he said.

Academic studies

In September 2015, the establishment of the peer-reviewed academic journal Ledger (.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}ISSN 2379-5980) was announced. It covers studies of cryptocurrencies and related technologies, and is published by the University of Pittsburgh.[96]

The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which will then be timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address in the first page of their papers.[97][98]

See also

- 2018 crypto crash

- Crypto-anarchism

- Cryptocurrency bubble

- Cryptocurrency exchange

- Cryptographic protocol

- List of cryptocurrencies

- Virtual currency law in the United States

References

^ ab Andy Greenberg (20 April 2011). "Crypto Currency". Forbes.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

^ Cryptocurrencies: A Brief Thematic Review Archived 25 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine.. Economics of Networks Journal. Social Science Research Network (SSRN). Date accessed 28 August 2017.

^ Schueffel, Patrick (2017). The Concise Fintech Compendium. Fribourg: School of Management Fribourg/Switzerland. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017.

^ Allison, Ian (8 September 2015). "If Banks Want Benefits of Blockchains, They Must Go Permissionless". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

^ Matteo D'Agnolo. "All you need to know about Bitcoin". timesofindia-economictimes. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015.

^ Sagona-Stophel, Katherine. "Bitcoin 101 white paper" (PDF). Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2012.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Pitta, Julie. "Requiem for a Bright Idea". Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

^ "How To Make A Mint: The Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash". groups.csail.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

^ Laurie, Law,; Susan, Sabett,; Jerry, Solinas, (11 January 1997). "How to Make a Mint: The Cryptography of Anonymous Electronic Cash". American University Law Review. 46 (4). Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

^ Wei Dai (1998). "B-Money". Archived from the original on 4 October 2011.

^ "Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists' Answer to Cash". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012.Around the same time, Nick Szabo, a computer scientist who now blogs about law and the history of money, was one of the first to imagine a new digital currency from the ground up. Although many consider his scheme, which he calls "bit gold", to be a precursor to Bitcoin

^ ab Jerry Brito and Andrea Castillo (2013). "Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers" (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

^ Bitcoin developer chats about regulation, open source, and the elusive Satoshi Nakamoto Archived 3 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine., PCWorld, 26 May 2013

^ abc Wary of Bitcoin? A guide to some other cryptocurrencies Archived 16 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine., ars technica, 26 May 2013

^ "UK launches initiative to explore potential of virtual currencies". The UK News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

^ Lansky, Jan (January 2018). "Possible State Approaches to Cryptocurrencies". Journal of Systems Integration. 9/1: 19–31. doi:10.20470/jsi.v9i1.335.

^ "The Dictionary Just Got a Whole Lot Bigger". Merriam-Webster. March 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

^ Yang, Stephanie (31 January 2018). "Want to Keep Up With Bitcoin Enthusiasts? Learn the Lingo". WSJ. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

^ Vigna, Paul (19 December 2017). "Which Digital Currency Will Be the Next Bitcoin?". WSJ. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

^ Hankin, Aaron (4 June 2018). "Bitcoin begins the week with a stumble; SEC announces adviser for digital assets". MarketWatch. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

^ ab Economist Staff (31 October 2015). "Blockchains: The great chain of being sure about things". The Economist. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

^ Badkar, Mamta (14 May 2018). "Fed's Bullard: Cryptocurrencies creating 'non-uniform' currency in US". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

^ "How Cryptocurrencies Could Upend Banks' Monetary Role". Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine., American Banker. 26 May 2013

^ ab Narayanan, Arvind; Bonneau, Joseph; Felten, Edward; Miller, Andrew; Goldfeder, Steven (2016). Bitcoin and cryptocurrency technologies: a comprehensive introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17169-2.

^ "Blockchain". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.Based on the Bitcoin protocol, the blockchain database is shared by all nodes participating in a system.

^ Iansiti, Marco; Lakhani, Karim R. (January 2017). "The Truth About Blockchain". Harvard Business Review. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.The technology at the heart of bitcoin and other virtual currencies, blockchain is an open, distributed ledger that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way.

^ Raval, Siraj (2016). "What Is a Decentralized Application?". Decentralized Applications: Harnessing Bitcoin's Blockchain Technology. O'Reilly Media, Inc. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-4919-2452-5. OCLC 968277125. Retrieved 6 November 2016 – via Google Books.

^ abc Krishnan, Hari; Saketh, Sai; Tej, Venkata (2015). "Cryptocurrency Mining – Transition to Cloud". International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications. 6 (9). doi:10.14569/IJACSA.2015.060915. ISSN 2156-5570.

^ Hern, Alex (17 January 2018). "Bitcoin's energy usage is huge – we can't afford to ignore it". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

^ "China's Crypto Crackdown Sends Miners Scurrying to Chilly Canada". 2 February 2018 – via www.bloomberg.com.

^ "Cryptocurrency mining operation launched by Iron Bridge Resources". World Oil. 26 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018.

^ "Bitcoin and crypto currencies trending up today - Crypto Currency Daily Roundup June 25 - Market Exclusive". marketexclusive.com. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

^ "Iceland Expects to Use More Electricity Mining Bitcoin Than Powering Homes This Year". Fortune. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

^ "Bitcoin Mining Banned for First Time in Upstate New York Town". 16 March 2018 – via www.bloomberg.com.

^ "Bitcoin mania is hurting PC gamers by pushing up GPU prices". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

^ "Graphics card shortage leads retailers to take unusual measures". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

^ "AMD, Nvidia must do more to stop cryptominers from causing PC gaming card shortages, price gouging". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

^ "Nvidia suggests retailers put gamers over cryptocurrency miners in graphics card craze". Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

^ Lee, Justina (13 September 2018). "Mystery of the $2 Billion Bitcoin Whale That Fueled a Selloff". Bloomberg.

^ "What You Need To Know About Zero Knowledge". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

^ Greenberg, Andy (2017-01-25). "Monero, the Drug Dealer's Cryptocurrency of Choice, Is on Fire". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

^ https://ethgasstation.info/. Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ https://bitinfocharts.com/comparison/bitcoin-transactionfees.html. Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ First U.S. Bitcoin ATMs to open soon in Seattle, Austin Archived 19 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Reuters, 18 February 2014

^ Commission, Ontario Securities. "CSA Staff Notice 46-307 Cryptocurrency Offerings". Ontario Securities Commission. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

^ "SEC Issues Investigative Report Concluding DAO Tokens, a Digital Asset, Were Securities". www.sec.gov. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

^ "Company Halts ICO After SEC Raises Registration Concerns". www.sec.gov. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

^ R Atkins (Feb. 2018). Switzerland sets out guidelines to support initial coin offerings. Financial Times. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

^ Kharpal, Arjun (12 April 2017). "Bitcoin value rises over $1 billion as Japan, Russia move to legitimize cryptocurrency". CNBC. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

^ "Regulation of Cryptocurrency Around the World" (PDF). Library of Congress. The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. June 2018. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

^ Fung, Brian (21 May 2018). "State regulators unveil nationwide crackdown on suspicious cryptocurrency investment schemes". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

^ Bitcoin's Legality Around The World Archived 16 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Forbes, 31 January 2014

^ Tasca, Paolo (7 September 2015). "Digital Currencies: Principles, Trends, Opportunities, and Risks". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2657598.

^ Samburaj Das (May 2018)Iran and Russia Consider Using Cryptocurrency to Evade US Sanctions: ReportCCN-Altcoin News. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

^ Thompson, Luke (2018-08-24). "Bank of Thailand to launch its own crypto-currency". Asia Times. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

^ Matsakis, Louise (30 January 2018). "Cryptocurrency scams are just straight-up trolling at this point". Wired. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

^ Weinglass, Simona (28 March 2018). "European Union bans binary options, strictly regulates CFDs". Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

^ Alsoszatai-Petheo, Melissa (14 May 2018). "Bing Ads to disallow cryptocurrency advertising". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

^ French, Jordan (2 April 2018). "3 Key Factors Behind Bitcoin's Current Slide". theStreet.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

^ Wilson, Thomas (28 March 2018). "Twitter and LinkedIn ban cryptocurrency adverts – leaving regulators behind". Independent. Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

^ Rushe, Dominic (25 March 2014). "Bitcoin to be treated as property instead of currency by IRS". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

^ On the Complexity and Behaviour of Cryptocurrencies Compared to Other Markets Archived 8 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine., 7 November 2014

^ Iwamura, Mitsuru; Kitamura, Yukinobu; Matsumoto, Tsutomu (28 February 2014). "Is Bitcoin the Only Cryptocurrency in the Town? Economics of Cryptocurrency and Friedrich A. Hayek". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2405790. hdl:10086/26493. SSRN 2405790.

^ abcde ALI, S, T; CLARKE, D; MCCORRY, P;

Bitcoin: Perils of an Unregulated Global P2P Currency

[By S. T Ali, D. Clarke, P. McCorry

Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle University: Computing Science, 2015.

(Newcastle University, Computing Science, Technical Report Series, No. CS-TR-1470)

^ Mt. Gox Seeks Bankruptcy After $480 Million Bitcoin Loss Archived 12 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine., Carter Dougherty and Grace Huang, Bloomberg News, 28 February 2014

^ ab Sarah Jeong, DEA Agent Who Faked a Murder and Took Bitcoins from Silk Road Explains Himself Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Motherboard, Vice (25 October 2015).

^ Nate Raymond, Ex-agent in Silk Road probe gets more prison time for bitcoin theft Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Reuters (7 November 2017).

^ Cyris Farivar, GAW Miners founder owes nearly $10 million to SEC over Bitcoin fraud Archived 29 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Ars Technica (5 October 2017).

^ Russell, Jon. "Tether, a startup that works with bitcoin exchanges, claims a hacker stole $31M". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

^ "Bitcoin Gold Hit by Double Spend Attack, Exchanges Lose Millions". CCN. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

^ Eric Lam, Jiyeun Lee, and Jordan Robertson (10 June 2018), Cryptocurrencies Lose $42 Billion After South Korean Bourse Hack, Bloomberg NewsCS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link)

^ Roberts, Jeff John (9 July 2018). "Another Crypto Fail: Hackers Steal $23.5 Million from Token Service Bancor". Fortune. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

^ "News releases AMF: 2018". The Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF). 15 March 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

^ Raeesi, Reza (23 April 2015). "The Silk Road, Bitcoins and the Global Prohibition Regime on the International Trade in Illicit Drugs: Can this Storm Be Weathered?". Glendon Journal of International Studies / Revue d'Études Internationales de Glendon. 8 (1–2). ISSN 2291-3920. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

^ Polgar, David. "Cryptocurrency is a giant multi-level marketing scheme". QZ.com. Quartz Media LLC. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

^ Analysis of Cryptocurrency Bubbles Archived 24 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine.. Bitcoins and Bank Runs: Analysis of Market Imperfections and Investor Hysterics. Social Science Research Network (SSRN). Accessed 24 December 2017.

^ McCrum, Dan (10 November 2015), "Bitcoin's place in the long history of pyramid schemes", www.ft.com, archived from the original on 23 March 2017

^ Kim, Tae (27 July 2017), "Billionaire investor Marks, who called the dotcom bubble, says bitcoin is a 'pyramid scheme'", www.cnbc.com, archived from the original on 5 September 2017

^ Cryptocurrency and Global Financial Security Panel at Georgetown Diplomacy Conf Archived 15 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine., MeetUp, 11 April 2014

^ Schwartzkopff, Frances (17 December 2013). "Bitcoins Spark Regulatory Crackdown as Denmark Drafts Rules". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

^ Sidel, Robin (22 December 2013). "Banks Mostly Avoid Providing Bitcoin Services. Lenders Don't Share Investors' Enthusiasm for the Virtual-Currency Craze". Online.wsj.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

^ decentralized currencies impact on central banks Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., rte News, 3 April 2014

^ Four Reasons You Shouldn't Buy Bitcoins Archived 23 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine., Forbes, 3 April 2013

^ Experiments in Cryptocurrency Sustainability Archived 11 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine., Let's Talk Bitcoin, March 2014

^ Want to make money off Bitcoin mining? Hint: Don't mine Archived 5 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine., The Week, 15 April 2013

^ Keeping Your Cryptocurrency Safe Archived 12 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine., Center for a Stateless Society, 1 April 2014

^ "Scamcoins". August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

^ Bradbury, Danny (25 June 2013). "Bitcoin's successors: from Litecoin to Freicoin and onwards". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

^ Morris, David Z (24 December 2013). "Beyond bitcoin: Inside the cryptocurrency ecosystem". Fortune. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

^ "PAUL KRUGMAN: Bitcoin is a more obvious bubble than housing was".

^ Krugman, Paul (26 March 2018). "Opinion - Bubble, Bubble, Fraud and Trouble" – via NYTimes.com.

^ "Warren Buffett: Cryptocurrency will come to a bad ending". CNBC.

^ Imbert, Fred (13 October 2017). "BlackRock CEO Larry Fink calls bitcoin an 'index of money laundering'". Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

^ "Introducing Ledger, the First Bitcoin-Only Academic Journal". Motherboard. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017.

^ "Editorial Policies". ledgerjournal.org. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016.

^ "How to Write and Format an Article for Ledger" (PDF). Ledger. 2015. doi:10.5195/LEDGER.2015.1 (inactive 2018-09-26). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2015.

Further reading

Chayka, Kyle (2 July 2013). "What Comes After Bitcoin?". Pacific Standard. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

Guadamuz, Andres; Marsden, Chris (2015). "Blockchains and Bitcoin: Regulatory responses to cryptocurrencies". First Monday. 20 (12). doi:10.5210/fm.v20i12.6198.

External links

Media related to Cryptocurrency at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cryptocurrency at Wikimedia Commons