Ottawa Senators (original)

| Ottawa HC | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1883 |

| History | 1883–1886 (independent) 1887 (AHAC) St. Louis Eagles: 1934–35 (NHL) |

| Home arena | Royal Rink (1883)[1] Dey's Rink (1884–1887) Rideau Rink (1889–1895,1898)[2] Dey's Arena (1896–1897,1898–1903) Aberdeen Pavilion (1904) Dey's Arena (1905–1907) The Arena (1908–1923) Ottawa Auditorium (1923–1954) |

| City | Ottawa, Ontario |

| Colours | Black, red, and white |

| Stanley Cups | 11 (1903, 1904, 1905, 1906,[3] 1909, 1910,[4] 1911, 1920, 1921, 1923, 1927) |

| Division championships | 8 NHL Canadian: 1927 NHA: 1911, 1915 CAHL: 1901 AHAC: (Jan-Mar 1892) OHA:1891,1892,1893 |

The Ottawa Senators were an ice hockey team based in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada which existed from 1883[1] to 1954. The club was the first hockey club in Ontario,[5] a founding member of the National Hockey League (NHL) and played in the NHL from 1917 until 1934. The club, which was officially the Ottawa Hockey Club (Ottawa HC), was known by several nicknames, including the Generals in the 1890s, the Silver Seven from 1903 to 1907 and the Senators dating from 1908.[6]

Generally acknowledged by hockey historians as one of the greatest teams of the early days of the sport, the club won numerous championships, starting with the 1891 to 1893 Ontario championships. Ottawa HC played in the first season during which the Stanley Cup was challenged in 1893, and first won the Cup in 1903, holding the championship until 1906 (the Silver Seven years). The club repeated its success in the 1920s, winning the Stanley Cup in 1920, 1921, 1923 and 1927 (the Super Six years). In total, the club won the Stanley Cup eleven times, including challenges during two years it did not win the Cup for the season. In 1950, Canadian sports editors selected the Ottawa HC/Senators as Canada's greatest team in the first half of the 20th century.[7]

The club was one of the first organized clubs in the early days of the sport of ice hockey, playing in the Montreal Winter Carnival ice hockey tournaments in the early 1880s and founding the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada and the Ontario Hockey Association. Along with the rise of professionalism in ice hockey in the first decade of the 1900s, the club changed to a professional team and were founding members of the National Hockey Association (NHA) and its successor, the National Hockey League. The club competed in the NHL until the 1933–34 season. Due to financial difficulties, the NHL franchise relocated to St. Louis, Missouri to become the St. Louis Eagles. The organization continued the Senators as an amateur, and later semi-professional, team in Quebec senior men's leagues until 1954. The "Senior Senators" would win three Allan Cup titles.

Contents

1 Team history

1.1 Early amateur era (1883–1902)

1.1.1 Formation of the AHAC

1.1.2 OHA championships

1.1.3 Re-entry into the AHAC

1.2 Silver Seven era (1903–1906)

1.2.1 Style of play

1.2.2 Dawson City challenge

1.2.3 Stanley Cup Challenge win streak

1.3 Early professional era (1907–1917)

1.3.1 Transition to professional (1907–1910)

1.3.2 National Hockey Association (1910–1917)

1.3.3 Stanley Cup champions in 1906 and 1910: Historians' debate

1.4 NHL years (1917–1934)

1.4.1 The 'Super Six' (1920–1927)

1.4.2 Decline (1927–1934)

1.4.3 1934: End of the first NHL era in Ottawa

2 Team information

2.1 Nicknames

2.2 Logos and sweaters

2.3 Ownership

2.4 Fans

3 Team record

3.1 List of Stanley Cup final appearances

4 Players

4.1 Hall of Famers

4.2 Team captains

4.3 Team scoring leaders (NHL)

5 See also

6 References

Team history

Early amateur era (1883–1902)

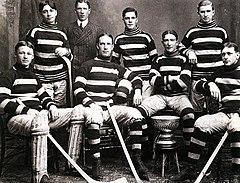

First photo of Ottawa Hockey Club, 1883–84.

Back row: L to R: T.D. Green, T. Gallagher, N. Porter.

Middle row, L to R: H. Kirby, J.Kerr, F. Jenkins.

Front row: L to R: G. Young, A. Low, E. Taylor

The Ottawa Hockey Club (Ottawa HC) was founded by a small group of like-minded hockey enthusiasts. A month after witnessing games of hockey at the 1883 Montreal Winter Carnival, Halder Kirby, Jack Kerr and Frank Jenkins met and founded the club.[8] Being the first organized ice hockey club in Ottawa, and also the first in Ontario, the club had no other clubs to play that season. The only activities that winter were practices at the "Royal Rink" starting on March 5, 1883.[9]

The club first participated competitively at the 1884 Montreal Winter Carnival ice hockey tournament (considered the Canadian championship at the time)[10] wearing red and black uniforms. Future Ottawa mayor Nelson Porter is recorded as the scorer of the club's first-ever goal, at the 1884 Carnival.[1] Frank Jenkins was the first captain of the team; he later became the president of the hockey club in 1891 and of the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHA or AHAC) in 1892.[8]

Ottawa Hockey Club, 1885

For the 1885 season, the club adopted gold and blue as its colours[11] and returned to the Montreal tournament. Ottawa earned its first-ever victory at the tournament over the Montreal Victorias, but lost its final match to the Montreal Hockey Club (Montreal HC) to place second in the tournament. The 1886 Montreal tournament was cancelled due to an outbreak of smallpox and the club would not play an outside match again until 1887.

Formation of the AHAC

On December 8, 1886, the first championship league, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada was founded in Montreal.[12] It was composed of several clubs from Montreal plus a Quebec City club and the Ottawa club. Ottawa's Thomas D. Green was named the first president of the league.[12] The league did not have a set schedule, and instead games were played in "challenge series", whereby a team held the championship and entertained challengers until the end of the season, a format the league employed until 1893. Under the format, Ottawa lost the one challenge it played in that first 1887 season to the Montreal Victorias.

After that season, Ottawa HC became inactive. The Royal Rink, which had been their primary facility, had been converted to a roller skating rink, and ice rink facilities were at a shortage. This changed with the opening of the Rideau Skating Rink in February 1889. One of the principal organizers in the restarting of the team was Ottawa Journal publisher P. D. Ross, who also played on the team. Returning as captain was Frank Jenkins, and the other players were Halder Kirby, Jack Kerr, Nelson Porter, Ross, George Young, Weldy Young, Thomas D. Green, William O'Dell, Tom Gallagher, Albert Low and Henry Ami.[13] In 1889, the club played only one match against an outside club, an exhibition at the Rideau rink against the Montreal HC 'second' team.[14]

In November 1889, the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club (OAAC) was opened at the corner of today's Elgin and Laurier Streets on the site of today's Lord Elgin Hotel. The Club building would also be the Hockey Club's headquarters. The OAAC was affiliated with the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association (OAAA), and the Hockey Club through the affiliation also became OAAA members. When the club began outside competition again in 1889–90, it was with new sweaters of white with black stripes and the OAAA red "triskelion" logo.[15] It was during this period of affiliation with the OAAC, that the club would become known by the nickname "Generals", attributed to the club's insignia.[16] The club is also referred to as the "Capitals" in literature, although there was a rival Ottawa Capitals club organized by the Capital Amateur Athletics Association active at the time.[16]

The 1891 Ottawa Hockey Club, Ottawa and Ontario champions.

Back Row, L to R: H. Kirby, Chauncey Kirby, Albert Morel, H.Y. Russell, F. Jenkins, W.C. Young, ?, ?

Front Row, L to R: R. Bradley, J. Kerr[17]

The team is posed with the Cosby Cup.

In the 1889–90 season, Ottawa HC played two competitive games but this was to increase greatly the next season. The 1890–91 season saw the club play 14 games, playing in three leagues. Ottawa HC was a founding member of two new leagues, the Ottawa City Hockey League (OCHL) and the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) and also rejoined the AHAC. Ottawa HC won the Ottawa and Ontario championships, and two games against AHAC opponents, but lost to the AHAC champion Montreal HC in its one challenge for the championship.[18]

OHA championships

The team was the OHA champion for that league's first three years. The first championship was played on March 7, 1891, at the Rideau rink and was won 5–0 by Ottawa over Toronto St. George's.[19] The 1891 championship was the only OHA final played in Ottawa, as Ottawa played the 1892 final in Toronto, defeating Osgoode Hall 4–2, and in 1893 the Toronto Granites defaulted by not appearing for the championship match scheduled for Ottawa. The club resigned from the OHA in February 1894 after the OHA refused the club's demand to have the 1894 final in Ottawa and ordered Ottawa HC to play the final in Toronto.[20] The dispute caused a permanent schism between Ottawa area teams competing in the Ottawa City Hockey League (OCHL) and the Ontario Hockey Association. Ottawa and area teams remain unaffiliated with the OHA; the official association under Hockey Canada is Hockey Eastern Ontario, a descendant of the OCHL.

It was at a dinner to honour the 1892 OHA champions at the Russell Hotel that the Governor General, Lord Stanley, announced his new Dominion Challenge Trophy, now known as the Stanley Cup, for the Canadian champions.[21] Former player and president of the club, P. D. Ross, was selected by Stanley to be a trustee of the Cup.[22]

The 1895 Ottawa Hockey Club and executive.

Standing: P. D. Ross, G. P. Murphy, Chauncey Kirby, Don Watters.

Seated: Jim Smellie, Alf Smith, Harvey Pulford, Weldy Young, Joe McDougall.

Bottom row: Harry Westwick, Fred Chittick, H. Russell[23]

Re-entry into the AHAC

Ottawa HC did not win a game in its return to AHAC challenge play in 1890–91, but in the next season of AHAC play in 1891–92 the club won the league championship, and held it for most of the season, from January 10 until March 7, 1892. The club took the championship from Montreal HC, who were previously undefeated, and won five straight games before Montreal won the championship back by a 1–0 score in the last challenge of the season. Montreal's win in the final challenge was their only win of the season and their only one in four games against Ottawa.

Lord Stanley, who often attended Ottawa HC games, felt the loss of the title after holding it all season was an unsuitable way to determine the championship. In the letter announcing the Stanley Cup, Stanley suggested that the AHAC start a 'round-robin' type regular season format, which the AHAC implemented in the following season of 1892–93.[24] The key match-up in that season for Ottawa was a loss in the opening game of the season against the Montreal Victorias on January 7, 1893, as Ottawa split its season series with eventual winner Montreal HC, both teams otherwise winning all of their games. This loss provided the one game margin in the standings that led to Lord Stanley awarding the initial Cup to Montreal HC.[25]

In 1893–1894, Ottawa HC finished in a four-way tie for first in the AHAC standings. A playoff was arranged in Montreal for the championship between Ottawa, Montreal HC and Montreal Victorias (the other first place club, Quebec, having dropped out of the playoff). These games would be the first Stanley Cup playoff games ever played. As the 'away' team, Ottawa was given a bye to the final game.[26] On March 23, 1894, at the Victoria Rink, Ottawa and Montreal HC played for the championship. Ottawa scored the first goal, but Montreal would score the next three to win the game 3–1. Ottawa captain Weldy Young fainted from exhaustion at the end of the game.[27]

The 1901 club, CAHL (left trophy) and Ottawa (right shield) champions.

The club wore the same 'O' logo as the Ottawa Football Club that season.

For the period of 1894 to 1900, the club did not win the league championship, finishing as high as second several times, and fifth (last) once. For the 1896–97 season, the Ottawa club unveiled the first use of the 'barber-pole' style sweaters of horizontal bars of black, red and white. This basic style would be used by the club until 1954 except for the 1900 and 1901 seasons, when the team used a plain sweater with only the letter 'O' on the front, identical in design to the sweaters of the Ottawa Football Club, also an OAAA affiliate.

In 1898, the AHAC dissolved over the admission of the intermediate-level team Ottawa Capitals of the rival Capital Amateur Association to the AHAC by a vote of the league executive. The Capitals had won the intermediate championship of the AHAC and were eligible to join the senior ranks. After they were outvoted by the intermediate-level teams of AHAC which wanted to promote the Capitals to the senior-level, the senior-level Ottawa, Montreal HC, Montreal Victorias and Quebec clubs left the AHAC and formed the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL), shutting out the Capitals.[28]

The club won the CAHL 1901 season title, its first league championship since winning the OHA in 1893. It wished to challenge the Stanley Cup champion Winnipeg Victorias at first but chose not to after deliberating for a week after the season, although it also had the option to challenge in the 1902 season.[29] According to hockey historian Charles L. Coleman, it was due to the "lateness of the season".[30]The Ottawa Journal openly supported the idea, stating that the players were 'racked' and would be at a serious disadvantage to travel to Winnipeg.[31]

Notable players of this period included Albert Morel and Fred Chittick in goal, leaders of the league several times in goaltending, and future Hall of Famers Harvey Pulford, Alf Smith, Harry Westwick and brothers Bruce Stuart and Hod Stuart. It was during this period that the nickname Senators was first used; however, from 1903 to 1906, the team is better known as the Silver Seven.

Silver Seven era (1903–1906)

Group picture of the 1905 Ottawa "Silver Seven", Stanley Cup champions

The first "dynasty" of the Ottawa HC was from 1903 until 1906, when the team was known as the "Silver Seven".[32] The era started with the arrival of Frank McGee for the 1903 season and ended with his retirement after the 1906 season. Having lost an eye in local amateur hockey, he was persuaded, despite the threat of permanent blindness, to join the Senators. The youngest player on the team and standing 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) tall, he went on to score 135 goals in 45 games. In a 1905 challenge against the Dawson City, he scored 14 goals in a 23–2 win. He retired in 1906 at the age of 23.[33]

In the 1903 CAHL season, Ottawa and the Montreal Victorias both finished in first place with 6–2 records. The top scorers were the Victorias' Russell Bowie, who scored seven goals in one game and six in another, and McGee, whose top performance saw him score five goals in a game. The two clubs faced off in a two-game total goals series to decide the league championship and Stanley Cup. The first game, played in Montreal on slushy ice that made it a desperate struggle to score, ended 1–1. The return match in Ottawa, witnessed by three thousand fans, was on ice coated with an inch of water. The conditions did not hinder Ottawa, as they won 8–0, with McGee scoring three goals and the other five shared among the three Gilmour brothers, Dave (3), Suddy (1) and Bill (1), to win their first Cup.[34] This started a period in which the team held the Stanley Cup and defeated all challengers until March 1906.

For that Stanley Cup win, each of the team's players was given a silver nugget by team executive Bob Shillington, an Ottawa druggist and mining investor. He gave them nuggets instead of money since the players were still technically amateurs and to give them money would have meant disqualification from the league. In a 1957 interview, Harry Westwick recalled that at the presentation "One of the players said 'We ought to call ourselves the Silver Seven.' and the name caught on right there."[35] (At the time, hockey teams iced seven men—a goaltender, three forwards, two defencemen and a rover).

The Silver Seven moved between three leagues during this time, and for a time were independent of any league. In February 1904, during the CAHL season, Ottawa resigned from the league in a dispute over the replaying of a game. The team had arrived late for a game in Montreal and the game had been called at midnight, with a tied score. The league demanded that the game be replayed. The club agreed to play only if the game mattered in the standings. The impasse led to Ottawa leaving the league. For the rest of that winter, the club played only in Cup challenge series. Quebec went on to win the championship of the league and demanded the Stanley Cup, but the Cup's trustees ruled that Ottawa still retained it. The trustees offered to arrange a challenge between Ottawa and the CAHL champion, but the CAHL refused to consider it.[36] The next season, Ottawa joined the Federal Amateur Hockey League (FAHL), winning the league championship. The club was only in the FAHL for one season, and the Montreal Wanderers became their new rival. For the 1906 season Ottawa, along with the Wanderers and several of the CAHL teams, formed the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association (ECAHA), unifying the top teams into one league.[37]

Style of play

The Silver Seven were well known for the number of injuries that they inflicted on other teams. In a Stanley Cup challenge game in 1904, the Ottawas injured seven of the nine Winnipeg players, and the Winnipeg Free Press called it the "bloodiest game in Ottawa."[38] The next team to challenge the Ottawas, the Toronto Marlboroughs, were similar treated. According to the Toronto Globe:

The style of hockey seems to be the only one known and people consider it quite proper and legitimate for a team to endeavor to incapacitate their opponents rather than to excel them in skill and speed ... slashing, tripping, the severest kind of cross-checking and a systematic method of hammering Marlboroughs on hand and wrists are the most effective points in Ottawa's style.[38]

According to one player, the "Marlboroughs got off very easily. When Winnipeg Rowing Club played here, most of their players were carried off on stretchers."[38] This style of hockey would continue for years to come.

Dawson City challenge

The Silver Seven participated in perhaps the most famous[39][40][41] Stanley Cup challenge of all, that of Dawson City of the Yukon Territory in 1905. Organized by Joe Boyle, a Toronto-born prospector, who had struck it rich in the Yukon gold rush of 1898,[42] The Dawson City Nuggets had Lorne Hanna, who had played for Brandon against Ottawa in a 1904 challenge and two former elite hockey players: Weldy Young, who had played for Ottawa in the 1890s, and D. R. McLennan, who had played for Queen's College against the Montreal Victorias in an 1895 challenge. The remaining players were selected from other Dawson City clubs. Dawson City's challenge was accepted in the summer of 1904 by the Stanley Cup trustees and scheduled to start on Friday, January 13, 1905. The date of the challenge meant that Young had to travel separately to Ottawa, as he had to work in a federal election that December and would meet the club in Ottawa.[43]

Group picture of the Dawson City club, January 14, 1905, posed outside the Dey's Rink

To get to Ottawa, several thousand miles away, the club had to get to Whitehorse by overland sleigh, catch a train from there to Skagway, Alaska, then catch a steamer to Vancouver, B.C. and a train from there to Ottawa. On December 18, 1904, several players set out by dog sled and the rest left the next day by bicycle for a 330-mile trek to Whitehorse. At first the team made good progress, but the weather turned warm enough to thaw the roads, forcing the players to walk several hundred miles. The team spent the nights in police sheds along the road. At Whitehorse, the weather turned bad, causing the trains not to run for three days and the Nuggets to miss their steamer in Skagway. The next one could not dock for three days due to the ice buildup. The club found the sea journey treacherous, and it caused seasickness amongst the team. When the steamer reached Vancouver, the area was too fogged in to dock, and the steamer docked in Seattle. The team from there caught a train to Vancouver, from which it left on January 6, 1905, arriving in Ottawa on January 11.[44]

Despite the difficult journey, the Ottawas refused to change the date of the first game, only two days away. Ottawa arranged hospitable accommodations for the Dawson City team. The Yukoners received a huge welcome at the train station, had a welcoming dinner, and used the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club's rooms for the duration of their stay. Young did not arrive in time to play for Dawson.[45]

The first game was close at the halfway point, Ottawa leading Dawson three to one. In the second half, the play became violent. Norman Watt of Dawson tripped Ottawa's Art Moore, who retaliated with a stick to the mouth of Watt. Watt promptly knocked Moore out, hitting him on the head with his stick. The game ended 9–2 for Ottawa. The game left a poor taste in the mouth for the Yukoners, who complained that several goals were offside.[46]

After the game, Watt was quoted as saying "[Frank] McGee doesn't look like too much", as he had only scored once in the first game.[47][48] McGee scored four goals in the first half of the second match and 10 in the second half, leading Ottawa to a 23–2 score; his 14 goals remains a record for a single game of major senior hockey.[48] Eight of those 14 goals were scored consecutively in a span of less than nine minutes.[49] Despite this high score, the newspapers claimed that Albert Forrest, the Dawson City goalie, had played a "really fine game", otherwise the score "might have been doubled". Ottawa celebrated by hosting Dawson at a banquet. After this, the players took the Cup and attempted to drop-kick it over the Rideau Canal. The stunt was unsuccessful, as the Cup landed on the frozen ice and had to be retrieved the next day.[46]

Considering the lopsided score of the series, historians such as Paul Kitchen question why Dawson City was even granted a chance at the Cup. Dawson City had won no championships and did not belong to any recognized senior league. While team official Weldy Young knew Stanley Cup trustee P. D. Ross personally through their joint connection with the club, it may have been the political connections that Joe Boyle had with the government Interior Minister of the time, Clifford Sifton, that got Dawson City the series.[50]

Future Ottawa Senators owner Frank Ahearn later stated that Weldy Young had asked Ahearn to ask the Ottawa players to "not rub it in" as Dawson City did not expect to win. Ahearn mentioned this to McGee, who had had a row with Boyle when both were members of the Ottawa Rowing Club, and had not forgotten it.[51]

Stanley Cup Challenge win streak

The Ottawas were the dominant team for three years:

Defeated Montreal Victorias in two-game total goals series 1–1, 8–0 on March 7 and 10, 1903, to win CAHL championship, and the Stanley Cup.

Defeated Rat Portage Thistles in two-game total goals series 6–2,4–2 (10–4) on March 12–14, 1903.

Defeated Winnipeg Rowing Club in best-of three series 9–1, 2–6, 2–0 on December 30, 1903, and January 1–4, 1904.

Defeated Toronto Marlboroughs in two-game total goals series 6–3, 11–2 (17–5) on February 23–25, 1904.

Defeated Montreal Wanderers by forfeit, after tying Montreal 5–5 on March 2, 1904. The Wanderers refused to continue the series unless the tie was replayed, and forfeited as a result.

Defeated Brandon, Manitoba in two-game total goals series 6–3, 9–3 (15–6) on March 9–11, 1904.

Defeated Dawson City in best-of-three series 9–2, 23–2 (2–0) on January 13–16, 1905.

Won 1905 FAHL championship with record of 7 wins, 1 loss.

Defeated Rat Portage Thistles in best-of-three series 3–9, 4–2, 5–4 on March 7, 9 and 11, 1905.

Defeated Queens University in two-game total goals series 16–7, 12–7 (28–14) on February 27–28, 1906.

Defeated Smiths Falls, Ontario in two-game total goals series 6–5, 8–2 (14–7) on March 6–8, 1906.

The end of the streak came in March 1906. Ottawa and the Montreal Wanderers tied for the ECAHA league lead in 1906, forcing a playoff series for the league championship and the Cup. Montreal won the first game in Montreal by a score of 9–1. In the return match, Ottawa replaced their goaltender Billy Hague and used goaltender Percy LeSueur, formerly of Smiths Falls. In the return match in Ottawa, Ottawa overcame the eight-goal deficit, getting a 9–1 lead to tie the series by the midway point of the second half. Harry Smith then scored to put Ottawa ahead, only to have the goal ruled offside.[52] It was then that Lester Patrick of the Wanderers took it upon himself, scoring two goals to win the series 12–10. This was Frank McGee's last game and he scored two goals.[53]

- The players

Besides McGee, future Hall of Fame players Billy Gilmour, Percy LeSueur, Harvey Pulford, Alf Smith, Bouse Hutton and Harry Westwick played for the Ottawas. Alf Smith was also the coach. Other players of the 'Seven' included Arthur Allen, Dave Finnie, Arthur Fraser, Horace Gaul, Dave Gilmour, Suddy Gilmour, Jim McGee, Art Moore, Percy Sims, Hamby Shore, Charles Spittal, Frank White and Frank Wood.

The club was able to continue the streak despite the death of one of its members. Jim McGee, Frank McGee's brother, died after the 1904 season in a horseback riding accident.[54] He was also the Ottawa Football Club's captain at the time.[55] The funeral cortege was estimated at a half-mile in length, and it included Canadian prime minister Wilfrid Laurier.[56]

Early professional era (1907–1917)

Transition to professional (1907–1910)

Until the 1906–07 season, the players were not paid to play hockey, as the team was abiding by the principles of amateur sports. Ottawa HC had an advantage in attracting top players to its squad. The players could work for the government, and the work allowed the players to play for the team. Meanwhile, in the United States, the International Hockey League was paying players. In response to this, the ECAHA, while still having several purely amateur teams, started to allow professional players. The top teams could, therefore, compete for the top players and the gate attractions that they were. The only restriction was that the status of each and every player had to be publicized.[57]

The period saw the rivalry between the Senators and the Wanderers continue, and at times it was brutally contested. On January 12, 1907, a full-scale "donnybrook" took place between the two teams at a game in Montreal. Charles Spittal of Ottawa was described as "attempting to split Blachford's skull", Alf Smith hit Hod Stuart "across the temple with his stick, laying him out like a corpse" and Harry Smith cracked his stick across Ernie Johnson's face, breaking Johnson's nose.[58][59] Discipline was first attempted by the league at a meeting on January 18, in which the Victorias proposed suspending Spittal and Alf Smith for the season, but this was voted down and the president of the league resigned.[59] The police arrested Spittal, Alf and Harry Smith on their next visit to Montreal,[60] leading to $20 fines for Spittal and Alf Smith and an acquittal for Harry Smith.[59] The tactics did not work on the Wanderers; they won the return match in Ottawa in March and went undefeated for the season, leaving Ottawa in second place.[57] However, it may have affected the Wanderers in another way: they lost the Stanley Cup a week after the donnybrook in a Stanley Cup challenge series to the Kenora Thistles.

The 1909 Ottawa Hockey Club Stanley Cup champion

The 1907–08 season was a season of change for Ottawa. Harry Smith and Hamby Shore left to join Winnipeg. Ottawa hired several free agents, including Marty Walsh, Tommy Phillips and Fred 'The Listowel Whirlwind' Taylor.[61] Taylor was hired away from the International Professional Hockey League (IHL) for the 1908 season for a $1000 salary and a guaranteed federal civil service job. He was an immediate sensation and earned a new nickname of 'Cyclone' for his fast skating and end-to-end rushes,[62] the nickname attributed to the Canadian governor-general Earl Grey.[63] Phillips was signed from Kenora to an even higher salary of $1,500 for the season, partially paid for by Ottawa sportsmen.[64]

Ottawa moved into their new arena, simply dubbed The Arena, with seating for 4,500 and standing room for 2,500.[65] With the free agent signings and the new arena, Ottawa started selling season-tickets, the first of their kind, $3.75 for five games, eventually selling 2,400.[64] The capacity was topped with a crowd of 7,100 in the home opener, attending a game against the Wanderers on January 11, which Ottawa won 12–2. However, Ottawa started the season with two losses out of three games and ended in second place behind the Wanderers again.[66] Walsh tied for the scoring lead with 28 goals in 9 games (including 7 in one match), while Phillips was close behind at 26 goals in 10 games.

In 1908–09, the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association became completely professional and changed its name to the Eastern Canada Hockey Association (ECHA). This led to the retirement of several stars, including Ottawa's Harvey Pulford and Montreal's Russell Bowie, who insisted on keeping their amateur status.[67] The Montreal Victorias and Montreal HC founded the Interprovincial Amateur Hockey Union, leaving only Ottawa, Quebec, Montreal Wanderers and Montreal Shamrocks in the ECHA. It was another season of player turn-over for Ottawa. Besides Pulford, Ottawa lost Alf Smith, who formed a competing Ottawa Senators professional team in the Federal League, and Tommy Phillips, who joined Edmonton. The club picked up Bruce Stuart from the Wanderers, Fred Lake from Winnipeg and Dubby Kerr from Toronto. This lineup had a successful season, winning 10 out of 12 games. Walsh led all scorers with 38 goals in 12 games, while Stuart had 22 and Kerr had 20. The season was clinched with a win against the Wanderers on March 3 in Ottawa, 8–3, as Ottawa won the league and Stanley Cup.[68]

Notable players of this time period include future Hall of Famers Percy LeSueur in goal, Dubby Kerr, Tommy Phillips, Harvey Pulford, Alf Smith, Bruce Stuart, Fred 'Cyclone' Taylor and Marty Walsh.

National Hockey Association (1910–1917)

The 1909–10 hockey season saw major changes in the hockey world, as the ECHA organization split and created two organizations, the Canadian Hockey Association (CHA) and the National Hockey Association (NHA). The CHA was formed to 'freeze out' the Wanderers, whose ownership change led the team to move to a smaller arena. At the same time, millionaire businessman J. Ambrose O'Brien, who wanted his Renfrew Creamery Kings to challenge for the Stanley Cup, saw his Renfrew application to join the CHA rejected. Together with the Wanderers, O'Brien instead decided to form the NHA, and founded the Montreal Canadiens.[69] The NHA became the fore-runner of today's National Hockey League.

Ottawa was one of the founders of the CHA and one of the teams that had rejected Renfrew. However, after a few poorly attended games showed that fans had no interest in the league, Ottawa and the Montreal Shamrocks abandoned the CHA to join the NHA.[70] Ottawa, the defending Stanley Cup champion and Wanderers' rival, was readily accepted by the NHA. This enabled Ottawa to continue the rivalry with the Wanderers and take in the gate revenues those games provided. The Wanderers won the championship in 1910, and Ottawa won in 1911 and 1915.[71]

It is during the NHA period that the nickname "Ottawa Senators" came into common usage. Although there had been a competing Senators club in 1909, and there had been mention of the Senators nickname as early as 1901, the nickname was not adopted by the club.[6] The official name of the Ottawa Hockey Club remained in place until ownership changes in the 1930s.

Star player Cyclone Taylor had defected to Renfrew, and despite a salary war with Renfrew, Ottawa managed to re-sign their other top players, Dubby Kerr, Fred Lake and Marty Walsh for the 1909–10 season.[70] On Taylor's first return in February 1910, he made a promise to score a goal while making a rush backwards against Ottawa. This led to incredible interest, with over 7,000 in attendance.[72] A bet of $100 was placed at the King Edward Hotel against him scoring at all.[73] Ottawa won 8–5 (scoring 3 goals in overtime) and kept Taylor off the scoresheet. Later in the season at the return match in Renfrew, Taylor made good on his boast with a goal scored backwards, although it was simply a goal scored on a backhand shot.[74] This was the final game of the season, and Ottawa had no chance at the league title and did not appear to have put in an effort in a 17–2 loss, considered "the worst trimming ever handed to a team wearing the Ottawa colors".[75]

Ottawa Hockey Team, NH Association World Champions and Stanley Cup Holders, 1911 (HS85-10-23753)

In 1910–11, the NHA contracted and imposed a salary cap, leading many of the Ottawa players to threaten to form a competing league. However, team owners controlled the rinks and the players accepted the new conditions. For Ottawa players, conditions did not deteriorate much as the club provided bonuses after the season.[76] Ottawa gained revenge for the previous loss to Renfrew by defeating Renfrew 19–5. The team went 13–3 to win the NHA and inherit the Stanley Cup; Marty Walsh and Dubby Kerr led the goal scoring with 37 and 32 goals in 16 games. After the season Ottawa played two challenges, against Galt, winning 7–4, and against Port Arthur, winning 13–4. In the Port Arthur game Marty Walsh came close to matching Frank McGee's total, scoring ten goals.[77] 1910–11 was the debut season of right winger Jack Darragh who scored 18 goals in 16 games.

The 1911–12 through 1913–14 seasons saw a decline for both Ottawa and the Wanderers. After the withdrawal of O'Brien's Renfrew team in 1911, the two clubs fought over the rights to Cyclone Taylor, who wanted to return to Ottawa, where his fiancé lived and he still had a government job. The NHA had given the Wanderers the rights to Taylor in a dispersal of the Renfrew players. Trade talks were unfruitful. Ottawa, insistent in their claim for Taylor, played him in one game for Ottawa against the Wanderers. The Senators won the game; however, Taylor was ineffectual.[78] The move backfired on the Senators, as the league ruled that the game could not stand and would have to be replayed. The Senators lost the replay and it was the difference in the league championship, as the defending champion Senators placed second by one game behind Quebec.[79] Quebec's Bulldogs won the only two Stanley Cup championships in the club's history that season and the next, and the Toronto Blueshirts won in 1914. Taylor did not play in the NHA again, as he joined Vancouver in the off-season.[80] The Senators finished fifth in 1912–13 and fourth in 1913–14. 1912–13 saw the debut of right winger Punch Broadbent, who scored 20 goals in 18 games.

Group photograph of the 1914–15 Ottawa Senators.

Some players' sweaters have a two flags logo for war-time.

In 1914–15, both Ottawa and the Wanderers bounced back to the top of league, tying each other for the NHA season title. This was also the season that future Hall of Famer Clint Benedict became the Senators' top goaltender, taking over from Percy LeSueur. Former Wanderer Art Ross joined the Senators and helped Ottawa win in a two-game playoff, 4–1. The Senators then played in the first inter-league Stanley Cup final playoff series with the Vancouver Millionaires of the Pacific Coast (PCHA) league. Cyclone Taylor, now of the Millionaires, haunted his old team, scoring six goals in three games as Ottawa lost three straight in Vancouver. Future Senator centreman Frank Nighbor played in this series for Vancouver and scored five goals.[81]

In 1915–16, the Senators placed second to the eventual Stanley Cup champion Montreal Canadiens. Punch Broadbent left the team to fight in World War I, while Frank Nighbor joined the Senators in his place and became the team's leading scorer. Nighbor had been signed away from Vancouver for the salary of $1,500, making him the highest paid player on the club, ahead of Art Ross and Eddie Gerard.[82] Benedict led the league as the top goaltender for the first time.[83] With the wartime shortage of players, Rat Westwick and Billy Gilmour of 'Silver Seven' days attempted comebacks with the club but both played only two games before retiring for good.[84]

In the off-season, Ottawa's president Llewellyn Bate proposed to suspend the team's operations until the end of the war. Gate receipts had declined 17 per cent. The other NHA owners refused to suspend the league. Rather than simply cease operations, Bate and the other directors of the team turned it over to Ted Dey, owner of the Arena. Dey cut player salaries and let players go, including Art Ross to the Wanderers. Dey also fired manager Alf Smith, saving on his $750 salary.[85]

In 1916–17, the last season of the NHA, Ottawa won the second half of the split schedule. An Army team, the Toronto 228th Battalion, composed of enlisted professional players, joined the league before leaving for war after the first half-season. When the Battalion left, the other Toronto team, the Blueshirts was suspended by the league and its players dispersed including Corb Denneny, brother of Cy Denneny, who joined the Senators. Future Hall of Famer Cy had been picked up in a trade with Toronto earlier that season and he would be a member of the Senators until 1928. Benedict was the NHA's top goaltender once again, and Nighbor tied for the scoring lead with 41 goals in 19 games.[86] As second-half winners, the Senators played off in a series with the Canadiens, the first-half winners. The Senators ended their play in the NHA by losing a two-game total goals playoff series to the Canadiens, who eventually lost to Seattle in the Stanley Cup final. This season saw the final decline of Ottawa's old rivals, the Wanderers, who finished at the bottom of the standings. The next year, the Wanderers played only four games in the NHL, winning only one before folding the franchise after their home arena burned down.[87]

While World War I affected all NHA teams, Ottawa was able to retain players and be competitive. The club finished no worse than second during the wartime seasons of 1914–15 to 1917–18.[88]

Stanley Cup champions in 1906 and 1910: Historians' debate

Due to the 'challenge' format of Stanley Cup play before 1915, there is often confusion about how many Stanley Cups the Senators should be given credit for: nine, ten or eleven. The Senators were Stanley Cup champions at the end of nine hockey seasons without dispute. In another two seasons, 1905–06 and 1909–10, the Senators won Stanley Cup challenges but were not champions at the end of the season. The Hockey Hall of Fame and the National Hockey League agree that the Senators of 1906 were champions but disagree on whether the Senators were champions in 1910. In both seasons, the Senators were the undisputed defending champions, and during that year's hockey season, the Senators won Stanley Cup challenges. However, by the end of both hockey seasons, they were no longer holders of the Stanley Cup.

In 1906, Ottawa defeated OHA champions Queen's University and FAHL champions Smiths Falls in Stanley Cup challenges. However, Ottawa tied the Montreal Wanderers for the ECAHA regular season championship. To decide the ECAHA championship and the Stanley Cup, the Senators played a two-game total goals series against the Wanderers in March 1906 and lost. The 1906 hockey season ended with the Wanderers as the Stanley Cup champions. The Hockey Hall of Fame recognizes both Ottawa and the Wanderers as champions for that year,[89] as does the NHL.[90]

In January 1910, Ottawa defeated Galt, champions of the OPHL, during the CHA regular season, as well as Edmonton of the AAHA during the NHA regular season (the Senators switched leagues in-between). At the end of the season Ottawa gave up the Cup to the Montreal Wanderers, regular-season champions of the new NHA league. Unlike the 1906 case, the Hockey Hall of Fame does not recognize the Senators as champions for January 1910,[89] although the NHL does.[90]

In October 1992, at the first game of the current Ottawa Senators NHL club, banners were raised to commemorate Stanley Cups in nine seasons, excluding 1906 and 1910. In media guides published by the club, they listed the original Senators as nine-time winners.[91] This changed in March 2003, when the team raised banners for the 1906 and 1910 years to join the other nine banners hanging at the Corel Centre. The club and the NHL now list the original Senators as eleven-time winners.[90]

NHL years (1917–1934)

Clint Benedict was outstanding for Ottawa

After struggling through the war years, the Ottawa Hockey Association put the Club up for sale for $5,000 in the fall of 1917. Montreal Canadiens' owner George Kennedy was leading an effort to get rid of Toronto Blueshirts' owner Eddie Livingstone, and he needed the Senators in his corner. He loaned Ottawa Citizen sports editor Tommy Gorman (who also doubled as a press representative for the Canadiens) $2,500 to help buy into the Senators. Gorman, along with Martin Rosenthal and Ted Dey (owner of The Arena), bought the club. At a meeting held at Montreal's Windsor Hotel, the Senators, Canadiens, Wanderers and Bulldogs formed a new league—the National Hockey League—effectively leaving Livingstone in the NHA by himself. Gorman represented the Senators at the meeting. "A great day for hockey", he was quoted as saying, "Without [Livingstone] we can get down to the business of making money."[92] Within a year, Gorman and partner Ted Dey had made enough money to pay back Kennedy. Gorman also attended the following year's meeting of the NHA owners in which the final vote to suspend the league was made.[93]

The Senators first season in the NHL, 1917–18, did not go well. Salary squabbles delayed the home opener (on the league's first night, December 19, 1917[94]) as players protested that their contracts were for twenty games, while the season schedule was for twenty four. Enough players were appeased that the game started, 15 minutes late, while two players Hamby Shore and Jack Darragh, stayed in the dressing room while negotiations went on.[95] The Senators lost their home opener 7–4. The Senators lost their previous top rival, the Wanderers, after five games. The team struggled and finished in third place after the first half of the season. The club made player changes in the second half, getting Horace Merrill out of retirement and releasing Dave Ritchie. It was Shore's last season as he would die of pneumonia in October 1918. Shore's last career game was in the third-last game of the season and he was sat out for the last two games.[96] In the end, the team placed second in the second half and missed the playoffs. Cy Denneny led the team, coming second overall in scoring in the league with 36 goals in 20 games.[97]

Prior to the 1918–19 season, ownership of the Senators changed. While Ted Dey negotiated with Percy Quinn for a lease for The Arena, Dey was also negotiating with Rosenthal over the lease, causing Rosenthal to seriously consider moving the team from The Arena back to Aberdeen Pavilion. However, it turned out that Dey was engineering a takeover of the club and Rosenthal ended up selling his share of the club to Dey, making Dey the majority owner in both the Arena and the hockey club. Rosenthal, a prominent local jeweller, had been involved with the club since 1903. Dey's machinations also helped the NHL in its continuing fight against Blueshirts owner Livingstone. The Senators instigated an agreement with the other NHL clubs, binding them to the NHL for the next five years and locking out any rival league from their arenas.[98]

In 1918–19, the Senators won the second half of the split schedule. Clint Benedict had the top goalkeeper average, and Cy Denneny and Frank Nighbor placed third and fourth in scoring with 18 and 17 goals in 18 games, respectively. The schedule was abbreviated by the Toronto Arenas club suspending operations, so the Senators and Canadiens played off in the first best-of-seven series. Due to a family bereavement, Ottawa was without star centre Frank Nighbor for the first three games and lost all three.[99] Ottawa asked to use Corb Denneny of Toronto, but the Canadiens turned down the request.[100] Nighbor returned for the fourth game in Ottawa, which Ottawa won 6–3. The series ended in five games, as the Canadiens won the final match 4–2 to win the series.[101] The Stanley Cup final between Montreal and Seattle was left undecided, as an influenza outbreak suspended the final.[102]

The 'Super Six' (1920–1927)

The "Super Six"[103] Senators of the 1920s are considered by the NHL to be its first dynasty.[104] The club won four Stanley Cups and placed first in the regular season seven times.[104] The team's success was based on the timely scoring of several forwards, including Frank Nighbor and Cy Denneny, and a defence-first policy, which led to the NHL changing the rules in 1924 to force defencemen to leave the defensive zone once the puck had left the zone.[105] The talent pool in Ottawa and the Ottawa valley was deep; the Senators traded away two future Hall of Famers (Clint Benedict and Harry Broadbent) in 1924 to make way for two prospects (Alex Connell and Hooley Smith), who would also become Hall of Famers.[106] Benedict and Broadbent led the Montreal Maroons to a playoff defeat of the Senators on the way to a Stanley Cup win in 1926.[107]

In the 1919–20 season, the NHL reactivated the Quebec Bulldogs NHA franchise; with this addition, the NHL played with four teams again. There were no playoffs, as Ottawa won both halves of the schedule, the undisputed NHL championship and the O'Brien Cup. Clint Benedict again led league in goalkeeper goals-against average and Frank Nighbor came third in the league scoring race with 25 goals in 23 games.[108]

The Senators then played the Seattle Metropolitans of the PCHA for the Stanley Cup. Because Seattle's red-white-green striped uniforms were nearly the same as Ottawa's red-white-black sweaters, the Senators played in simple white sweaters adorned with a large red "O" for this series.[109] The first three games were held in Ottawa (the first Stanley Cup games played in Ottawa since 1911) and ended with scores of 3–2 and 3–0 for Ottawa and 3–1 for Seattle. The first three games had been played on ice covered with water and slush due to warm weather in Ottawa. At this point, NHL president Calder moved the series to the Arena Gardens in Toronto, which had an artificial ice rink, the only one in eastern Canada at that time.[110] Seattle won 5–2 to tie the series, cheered on by the Toronto fans. In the fifth and deciding game, Ottawa won 6–1 on Jack Darragh's three goal performance and won their first Stanley Cup as a member of the NHL.[111] It was after this win that T. P. Gorman dubbed the team the 'Super Six.'[112]See the article 1920 Stanley Cup Finals.

In the 1920–21 season, the league transferred two Senators players to help its competitive balance. Punch Broadbent was transferred to Hamilton while Sprague Cleghorn was transferred to Toronto.[112] Even without the two, the Senators won the first half of the season to qualify for the playoffs. By the end of the playoffs, both players were back with Ottawa. Benedict again led league in goalkeeper average and Cy Denneny came second in scoring with 34 goals in 24 games. The Senators shut out Toronto 7–0 in a two-game total goals playoff and went west to play off against Vancouver for the Stanley Cup. Vancouver still had Cyclone Taylor, though it was near the end of his career and he scored no goals. The best-of-five series was heavily attended, with 11,000 fans attending the first game, the largest crowd in history to see a hockey game up until that time[113] and a total attendance for the five-game series of over 51,000.[114] Ottawa won the series with scores of 1–2, 4–3, 3–2, 2–3 and 2–1, with Jack Darragh scoring the winning goal.[115]See the article 1921 Stanley Cup Finals.

The 1921–22 season saw Sprague Cleghorn leave and Jack Darragh retire, opening spaces for new defencemen Frank Boucher and Frank "King" Clancy.[114] Clancy's first goal came on his first shot, against Hamilton in overtime on February 7, and was noted for having actually come in (illegally) through the side of the net.[116] Broadbent and Cy Denneny, the "Gold Dust Twins", finished one and two in league scoring, together producing 59 of Ottawa's 106 goals.[114] Broadbent scored in 16 consecutive games, an NHL record, that as of 2009, still stands.[117] The Senators won the regular season title but lost to eventual Stanley Cup winner Toronto St. Patricks 5–4 in a two-game total goals series. The series had the Boucher brothers play for Ottawa, while Cy Denneny played for Ottawa and his brother Corbett played for Toronto.[118]

The 1922–23 Stanley Cup championship patch worn on their 1923–24 sweaters

In 1922–23, the Senators were led by the league's top goalie Clint Benedict, the goal scoring of Cy Denneny and the return from retirement of Jack Darragh.[119] The season also saw the debut of defenceman Lionel Hitchman. An unsurpassed iron man record was set when Frank Nighbor played in six consecutive games without substitution, averaging a goal a game during the stretch.[120] The Senators won the regular season and took the playoff against the Canadiens 3–2 in a two-game total-goals playoff.[121]

The Cup Final playoff format had changed. There were semi-finals against the PCHA champion, followed by the final against the WCHL champion. In the Cup semi-finals, Ottawa again faced Vancouver (now known as the Maroons) in Vancouver. New attendance records were set during this series, with 9,000 for the first game and 10,000 for the second. Ottawa won the series with scores of 1–0, 1–4, 3–2, and 4–1, with Benedict getting the shutout and Harry Broadbent scoring five goals. The Senators next had to play Edmonton in a best-of-three series and won it in two games with scores of 2–1 and 1–0, with Broadbent scoring the winning goal.[122] The second game of the finals is famous for being the game in which King Clancy (then only a substitute for the team) played all positions, including goal.[123]See the article 1923 Stanley Cup Finals.

That year, club owners Dey and Gorman entered into a partnership with Frank Ahearn. Ahearn's family was well-off, owning the Ottawa Electric Company and the Ottawa Street Railway Company. Ted Dey then sold his share of the club and retired.[124] The first work of the partnership was a new arena, the Ottawa Auditorium, which was a 7,500 seat (10,000 capacity with standing room) arena with artificial ice. The new Ottawa Auditorium's first regular season game came on December 26, 1923. A crowd of 8,300 fans attended a game against the Canadiens, in which rookie Howie Morenz scored his first NHL goal.[125]

The 1923–24 season saw the Senators win the season but lose the playoff to the Canadiens, 0–1 and 2–4, with Georges Vezina getting the shutout and Morenz scoring 3 goals. Frank Nighbor was the first winner of the Hart Trophy as 'most valuable player' for his play in the regular season.[126] After the disappointing loss in the playoff series, goaltender Clint Benedict became embroiled in a controversy with the club over late nights and drinking. He was traded away, along with Harry Broadbent, to the new Montreal Maroons before the next season, for cash.[127] Ottawa hockey fans got to see a Stanley Cup final game played in Ottawa as the Auditorium hosted the final match of the Stanley Cup finals between the Canadiens and the Calgary Tigers, moved because of poor natural ice at the Canadiens' arena.[128]

Frank Nighbor with original Hart Trophy

The 1924–25 season, the first year of NHL expansion to the United States, saw major changes in Ottawa's lineup. Jack Darragh retired and had died from appendicitis months after his final game.[129] Making his debut in goal for Ottawa was Alex Connell, replacing Benedict. Replacing Broadbent was Hooley Smith, who had played for Canada in the 1924 Olympics. Lionel Hitchman was sold to the expansion Boston Bruins and replaced by Ed Gorman. It was also the debut season of Frank Finnigan.[126] Off the ice, Gorman and Ahearn squabbled over ownership. In January 1925, during the season, Gorman sold his share of the Senators to Ahearn and left the Senators organization, later joining the expansion New York Americans.[126]

With all the changes, the Senators slipped to fourth place in the standings. Cy Denneny continued his scoring ways, placing fourth in league scoring with 28 goals in 28 games.[130] Frank Nighbor became the first winner of the Lady Byng Trophy for gentlemanly play, donated by Marie Evelyn Moreton (Lady Byng), wife of Julian Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy, who was Governor General of Canada from 1921 to 1926. Nighbor received the trophy personally from Lady Byng during a presentation at Rideau Hall.[126] Nighbor won the trophy in 1925–26 and 1926–27 as well.

The NHL expanded further into the United States in the 1925–26 season with the new New York Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates. Ottawa won the league title, led by Alex Connell in goal, who recorded 15 shutouts in 36 games, and Cy Denneny, who scored 24 goals. The team received a bye to the playoff finals.[131] However, the Montreal Maroons won the two-game total goals series with scores of 1–1 and 1–0; former Senator Clint Benedict got the shutout. The Maroons went on to win the Stanley Cup against Victoria.[132] The season also marked the debut of future Hall of Famer Hec Kilrea.

The 1926–27 season saw the NHL divided for the first time into two divisions, and they made the playoffs, winning the Canadian Division title. They advanced to the semi-finals and defeated the Canadiens, 4–0, and 1–1, en route to facing the Boston Bruins for the Cup. In the first series for the Stanley Cup with only NHL opponents, Ottawa defeated Boston with scores of 0–0, 3–1, 1–1 and 3–1, with the final game taking place in Ottawa; it would be the Senators' final Stanley Cup championship.[133] Alex Connell led the way in goal, allowing only three goals in the four games. Cy Denneny led the way in scoring with four goals, including the Cup winner. The Senators won three trophies as NHL champions, along with the Stanley Cup, the club also won two other trophies, the O'Brien Cup and the Prince of Wales Trophy, the last time the trophies were given to winners of the NHL championship. They would be given out to divisional winners in the following season. After the series, the Senators players received a parade in Ottawa, a civic banquet and an 18–carat gold ring with fourteen small diamonds in the shape of an 'O'.[134]See the article 1927 Stanley Cup Finals.

Decline (1927–1934)

Ottawa had been by far the smallest market in the NHL even before American teams began playing in 1924. The later 1931 census listed only 110,000 people in the city of Ottawa—roughly one-fifth the size of Toronto, which was the league's second-smallest market. The team sought financial relief from the league as early as 1927. Despite winning the Stanley Cup, the Senators were already in financial trouble, having lost $50,000 for the season.[135] The league's expansion to the United States did not benefit the Senators. Attendance was low for games against the expansion teams, which provided a poor gate at home. There were also higher travel costs for away games, although the American arenas were larger. This fact was the basis for attempts to increase revenues, as the team played "home" games in other cities.

In the 1927–28 season, the Senators played two "home" games in Detroit, collecting the bulk of the gate receipts (thus allowing them to actually turn a profit for that season), while Jack Adams retired to become the coach and general manager of the Detroit Cougars.[133] The brightest note from the campaign was goaltender Alex Connell's play, in which he set a NHL record (unsurpassed as of 2016) of six consecutive shutouts, a shutout run of 460 minutes and 49 seconds.[136]

Taking advantage of a spending spree by the Montreal Maroons at the onset of the 1928–29 season,[136] the Senators sold their star right wing Hooley Smith to the Maroons for $22,500 and the return of former star Punch Broadbent.[137] Also for cash, the team sent long-time member Cy Denneny to the Bruins. The club further repeated the scheme of playing two "home" games in Detroit en route to an undistinguished campaign in which they missed the playoffs for only the third time in the NHL's history.[137][138]

In the 1929–30 season, with cash still hemorrhaging, the team transferred two scheduled home games to Atlantic City (one each against the New York Rangers and New York Americans), two to Detroit, and one to Boston.[139] The Senators rallied, however, to make the playoffs for a final time, finishing third in the Canadian Division. The Senators faced off against the New York Rangers in a two-game total-goals series. In the last NHL playoff game in Ottawa until 1996, the Senators tied the Rangers 1–1 on March 28, 1930, but lost game two in New York 5–1 to lose the series 6 goals to 2.[140] The season also marked the debut of future star Syd Howe with the Senators while long-time star Frank Nighbor was sold to Toronto.

By the 1930–31 season, the team was openly selling players to make ends meet. Star defenceman King Clancy was sold to Toronto for an unprecedented $35,000 and two players on October 11, 1930. The team fell into last place for the first time since 1898.[141] In 1931, a potential deal arose with the owners of Chicago Stadium, including grain magnate James E. Norris, who wanted to move the team to Chicago, but the deal was vetoed by Chicago Black Hawks owner Frederic McLaughlin who did not want another team in his territory.[142] Norris bought the bankrupt Detroit Falcons instead and turned them into the Detroit Red Wings.

The Senators and the equally strapped Philadelphia Quakers asked the NHL for permission to suspend operations for the 1931–32 season in order to rebuild their fortunes. The league granted both requests on September 26, 1931. Ottawa received $25,000 for the use of its players, and the NHL co-signed a Bank of Montreal loan of $28,000 to the club.[142] The Senators seriously considered moving to Toronto, as Conn Smythe desired a second tenant for the new Maple Leaf Gardens. However, they balked when Smythe wanted a $100,000 guarantee, with a 40%/60% split of revenues.[142]

Returning after a one-year hiatus and despite the return of players such as Cooney Weiland, Finnigan, Howe and Kilrea, the Senators finished with the worst record in the league in the two seasons that followed. Attendance was poor, the club only drawing well when the league's other three Canadian teams came to town.[135] Frank Finnigan recalled that they frequently played home games before small crowds of 3,500 to 4,000.[135]1932–33 saw the return of Cy Denneny to Ottawa as coach. He would last only the one season. In June 1933, former captain Harvey Pulford was given an option to buy the team and move it to Baltimore, but the option was never exercised.[143] In October 1933, Kilrea was sold for $10,000 to Toronto.[144]

In December 1933, rumours surfaced that the Senators would merge with the equally strapped New York Americans; however, this was denied by Ottawa club president Frank Ahearn, who had sought financial help from the league.[145] The team played the full 1933–34 season, transferring one home game to Detroit. Near the end of the season, reports surfaced that the club had entered into a deal with St. Louis "interests" to move the club.[146] The team lost its last home game by a score of 3–2 to the Americans on March 15, 1934, before a crowd of 6,500. The Senators had lent Alex Connell to the Americans when the Americans' goalie Worters was hurt, and he turned in a "sensational performance" for the visitors.[147] The home crowd was in a "throwing mood" and "carrots, parsnips, lemons, oranges and several other unidentified objects were thrown onto the ice continuously for no reason whatsoever."[148] The final game of the season was a 2–2 tie with the Maroons at the Montreal Forum on March 18, 1934.[149]

1934: End of the first NHL era in Ottawa

The April 7, 1934, Ottawa Citizen headline

Despite finishing in last place for the second year in a row, the Senators actually improved their attendance over the previous season. Even with the increased gate, they barely survived the season. After the season ended, it was announced by Auditorium president F. D. Burpee that the franchise would not return to Ottawa for the 1934–35 season due to losses of $60,000 over the previous two seasons. The losses were too great to be made up by the sale of players' contracts, and the club needed to be moved to "some very large city which has a large rink, if we are to protect the Auditorium shareholders and pay off our debts."[150] The NHL franchise was moved to St. Louis, Missouri and operated as the St. Louis Eagles. The Eagles played only one season, finishing last again. They suspended operations after the season, never to return.[151]Flash Hollett was the last member of the Senators to play in the NHL, retiring with the Detroit Red Wings in 1946.

The city of Ottawa did not have an NHL franchise again until the new Ottawa Senators franchise was awarded for the 1992–93 season. The NHL presented the Senators with a "certificate of reinstatement" commemorating Ottawa's return to the league, and the current Senators honour the original franchise's 11 Stanley Cups. However, records for the two teams are kept separately. Frank Finnigan, the last surviving member of the original Senators' last Stanley Cup winner, played a key role in the drive to win an expansion franchise for Ottawa. He was slated to drop the puck in a ceremonial face-off for the new franchise's first game, but died a year before that game took place. The new Senators honoured Finnigan by retiring his #8 jersey.[152]

After the NHL franchise relocated, the Senators were continued as a senior amateur club in the Montreal Group of the Quebec Amateur Hockey Association (QAHA), beginning in the 1934–35 season.[153] One player, Eddie Finnigan, played for both the Senators and the Eagles in the 1934–35 season. The "Senior Senators" renewed the rivalry with Montreal-area senior amateur teams such as the Montreal Victorias that the old Senators had played in the years prior to turning openly professional. Later, Tommy Gorman bought the team and helped to found the Quebec Senior Hockey League. Winning the Allan Cup in 1949, the senior Senators continued until December 1954, finally ending the Senators' storied 71-year history.[154]

Team information

The first logo of Ottawa Hockey Club.

(based on logo of Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association)

Nicknames

The club began in 1883 as the Ottawa Hockey Club and was known by that name officially, even after joining the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association (OAAA). Reports of the club in early play in the 1890s sometimes refer to the club as the Generals. The club is also referred to as the Capitals, although there was a competing Capital Athletic Association hockey team using that name. Other nicknames included the Silver Seven, a name the players gave themselves after receiving silver nuggets from manager Bob Shillington after the 1903 Stanley Cup win.[35] The Super Six name was given in the 1920s.[103]

The first reference to the nickname of Senators was in a game report ("The Ottawas Made a Good Start") of the Ottawa Journal on January 7, 1901[155][156] and used in other newspapers around that time.[157] While the nickname was used occasionally, the club continued to be known as the Ottawa Hockey Club. In 1909, a separate Ottawa Senators pro team existed in the Federal League. Ottawa newspapers referred to that club as the Senators, and the Ottawa HC as 'Ottawa', 'Ottawas' or the 'Ottawa Pro Hockey Club'. The Globe newspaper of Toronto first refers to the Ottawa Hockey Club as the Senators in an article entitled 'Quebec defeated Ottawa' on December 30, 1912.[158] Eventually this became the official nickname, and was the only name used in descriptions of the club in NHL play.

Logos and sweaters

1896–1897 Ottawa Hockey Club.

The team is in their 'barber-pole' sweaters.

For the first two years of their existence, Ottawa used red and black horizontally-striped sweaters.[159] The club then changed to sweaters of gold and blue[11] until it later affiliated with the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association in 1889. The team then adopted the colours of the OAAA organization: red, white and black. The logo of the team was a simplified version of the 'triskelion' or 'winged legs' logo of the OAAA, which can be described as a "running wheel". The sweaters were solid white with the club logo in red. The players wore knee-length white pants with black stockings,[15] as shown in the 1891 team photo.

In 1896, the club first adopted the "barber-pole" design, with which the team became synonymous. The design was simple: strong horizontal stripes of red, black and white. Players wore white pants and red, white and black striped stockings. The basic design would be used for the rest of the organization's existence, except for one season, 1909–10, where the stripes were vertical and Montreal fans nicknamed the team derisively as 'les suisses', a slang term for chipmunk.[160] The "barber-pole" uniform was later adopted by the Ottawa 67's junior ice hockey team.

No logo was present on the sweater at first, and until 1930 logos were not used for more than a year at a time. During World War I, the club adopted a logo of flags to show allegiance to the war effort, as shown in the 1915 photo. After each Stanley Cup win, the club affixed a badge or logo stating "World Champions". In the 1929–30 season, the club added the "O" logo to the chest of the sweater.[161]

Bruce Stuart in 1909–10 sweater

Ownership

From the start, the club was owned and operated by its members and known as the Ottawa Hockey Club, becoming an affiliate of the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association in 1889. In 1907, according to hockey historian Charles L. Coleman, some of the ownership was transferred to five of the players: Smith, Pulford, Moore, Westwick and LeSueur.[61] In 1911, the club incorporated itself and the organization took on the name of the "Ottawa Hockey Association".[162] In 1917, the club was separated from the Association and sold to Tommy Gorman, Ted Dey and Martin Rosenthal for $5,000 in time to join the National Hockey League.[93]

In 1918, Rosenthal was forced out by Dey in a complex scheme. Dey was negotiating, as owner of The Arena, with both Rosenthal on behalf of the Senators and Percy Quinn (who held an option to purchase the Quebec NHA club) on behalf of a proposed new professional league over exclusive rights to the Arena for professional hockey. In a plan to derail the proposed new league, Dey maintained publicly that he had reserved the Arena for Quinn's proposed league when, in fact, he had not cashed a cheque received from Quinn to reserve an option on the Arena. Rosenthal, believing the club could no longer play at the Arena, attempted to find alternate arrangements for the club, including refurbishing Aberdeen Pavilion, but was unsuccessful. Dey purchased Rosenthal's share of the club on October 28, 1918, and Rosenthal resigned from the club.[163] Quinn filed a lawsuit against Dey for his deception but it was dismissed.[164] Quinn would get further action from the NHL, as the NHL suspended Quinn's franchise and took over its players' contracts.[165]

In 1923, Dey retired after selling his ownership interest to Gorman and new investor Frank Ahearn.[124] Ahearn and Gorman had an uneasy partnership and at one point Gorman was going to buy out Ahearn. By January 1925, the deal was nearly finalized when Gorman backed out of the deal.[166] Instead, Ahearn bought Gorman's interest in the club for $35,000 and a share of the Connaught Park Racetrack[126] and Gorman moved on to New York to manage the New York Americans. In 1929, Ahearn sold the club to the Ottawa Auditorium corporation for $150,000, financed by a share issue. William Foran, the Stanley Cup trustee, became president of the Club. As the Auditorium did not meet its payments, Ahearn resumed a share of the club in 1931.[167]

Likeness of 1930s 'barber pole' sweaters with 'O' logo

In 1931, a dispute arose between Foran, in his role as Stanley Cup trustee, and the NHL. The American Hockey League had asked for a Stanley Cup challenge against the champions of the NHL. Foran had agreed to the challenge and ordered the NHL to comply, but the NHL refused to play the challenge. Foran was fired from his position as Senators' president and was replaced by Redmond Quain.[168]

While the Ottawa Auditorium owned the hockey club, it was heavily indebted to Frank Ahearn and his father, and tried to clear its debt. In December 1930, the club was put up for sale for $200,000 under conditions it stay in Ottawa.[169] The best local bid was $100,000,[170] while a bid to move the club to Chicago was made for $300,000, ultimately denied by the Chicago Blackhawks ownership.[171] Later, the Auditorium tried to relocate the team to Baltimore under the ownership of former player Harvey Pulford.[169] A possible relocation to Toronto was also explored,[172] but in the end, no sales occurred.

In 1934, the club's NHL franchise was transferred to St. Louis, although the Association continued its ownership of the franchise and player contracts as well as the senior club. On October 15, 1935, the NHL bought back the franchise and players' contracts for $40,000 and suspended its operations again.[173] Under the agreement, the NHL paid for the players and took back possession of the franchise. If the franchise was resold, the proceeds would go to the Ottawa Hockey Association.[174]

In July 1936, the Auditorium bond-holders foreclosed on the arena and it was put under the control of the Royal Securities Corporation. The senior club was sold in 1937 to James MacCaffery, the owner of the Ottawa Rough Riders football team. Former owner Tommy Gorman returned to Ottawa in 1944, when he purchased the club and the Auditorium.[175] He operated the senior team until December 1954, when he shut down the team over falling attendance, citing the "rise of hockey on television."[154][176]

Fans

When the Ottawa Hockey Club began play, there was no division between the ice surface and the stands like today. The fans became quite wet in the times when the temperature was warm. In the 1903 Stanley Cup Final against the Montreal Victorias, the Governor-General (who had a private box seat at the ice's edge) is recorded as getting wet from the play.[177] On another occasion, in the 1906 Stanley Cup Final against the Wanderers, the Governor-General's top hat was knocked off by the stick of Ernie "Moose" Johnson.[53] The top hat was taken by a fan and given to Johnson.[178]

One custom of the Ottawa fans towards opposition teams was to throw lemons. Cyclone Taylor, on his first visit back to Ottawa after signing with Renfrew, was pelted with lemons as well as a bottle.[179]

Team record

List of Stanley Cup final appearances

Stanley Cup banners hanging at the Canadian Tire Centre, honouring the original Senators

| Date | Opponent | Result |

|---|---|---|

| March 22, 1894 | Montreal Hockey Club | Montreal defeats Ottawa 3–1 |

| March 7–8, 1903 | Montreal Victorias | Ottawa wins series (1–1, 8–0) |

| March 12–14, 1903 | Rat Portage Thistles | Ottawa wins series (6–2, 4–2) |

| December 30, 1903 – January 4, 1904 | Winnipeg Rowing Club | Ottawa wins series (9–1, 2–6, 2–0) |

| February 23–25, 1904 | Toronto Marlboroughs | Ottawa wins series (6–3, 11–2) |

| March 2, 1904 | Montreal Wanderers | Ottawa ties Montreal (5–5)[A] |

| March 9–11, 1904 | Brandon Wheat Cities | Ottawa wins series (6–3, 9–3) |

| January 13–16, 1905 | Dawson City Nuggets | Ottawa wins series (9–2, 23–2) |

| March 7–11, 1905 | Rat Portage Thistles | Ottawa wins series (3–9, 4–2, 5–4) |

| February 27–28, 1906 | Queen's University | Ottawa wins series (16–7, 12–7) |

| March 6–8, 1906 | Smiths Falls | Ottawa wins series (6–5, 8–2) |

| March 14–17, 1906 | Montreal Wanderers | Montreal wins series (9–1, 3–9) |

| 1909 | Ottawa goes unchallenged (ECHA champions) | |

| January 5–7, 1910 | Galt | Ottawa wins series (12–3, 3–1) |

| January 18–20, 1910 | Edmonton | Ottawa wins series (8–4, 13–7) |

| March 13, 1911 | Galt | Ottawa wins 7–4 |

| March 16, 1911 | Port Arthur | Ottawa wins 13–4 |

| March 22–26, 1915 | Vancouver Millionaires | Vancouver wins series (6–2, 8–3, 12–3) |

| March 22 – April 1, 1920 | Seattle Metropolitans | Ottawa wins series (3–2, 3–0, 1–3, 2–5, 6–1) |

| March 21 – April 4, 1921 | Vancouver Millionaires | Ottawa wins series (1–2, 4–3, 3–2, 2–3, 2–1) |

| March 16–26, 1923 | Vancouver Maroons | Ottawa wins series (1–0, 1–4, 3–2, 5–1) |

| March 29 & 31, 1923 | Edmonton Eskimos | Ottawa wins series (2–1, 1–0) |

| April 7–13, 1927 | Boston Bruins | Ottawa wins series (0–0, 3–1, 1–1, 3–1) |

- A. ^ Montreal refused to continue the series in Ottawa, thereby losing by default.

Players

Hall of Famers

- Jack Adams

Thomas Franklin Ahearn (builder)- Clint Benedict

- Frank Boucher

- George Boucher

- Punch Broadbent

- Harry Cameron

- King Clancy

- Sprague Cleghorn

- Alec Connell

- Bill Cowley

- Rusty Crawford

- Jack Darragh

- Cy Denneny

- Eddie Gerard

- Billy Gilmour

- Syd Howe

- Bouse Hutton

- Percy LeSueur

- Frank McGee

- Frank Nighbor

- Tommy Phillips

- Harvey Pulford

- Gordon Roberts

- Art Ross

P. D. Ross (builder)- Alf Smith

- Hooley Smith

- Tommy Smith

- Bruce Stuart

- Hod Stuart

- Fred "Cyclone" Taylor

- Carl Voss

- Marty Walsh

- Cooney Weiland

- Harry Westwick

Source: Ottawa Senators[180]

Team captains

Frank Jenkins 1883–86, 1889–90[8]

Thomas D. Green, 1886–87[181]

P. D. Ross, 1890–91[182]

Herbert Russell 1891–93[24][183]

Weldy Young, 1893–95

Chauncey Kirby, 1895–96[184]

Fred Chittick, 1896–97[185]

Harvey Pulford, 1897–98[186]

Chauncey Kirby, 1898–99[187]

Hod Stuart, 1899–1900[188]

Harvey Pulford, 1900–01

William Duval, 1902[189]

Harvey Pulford, 1902–06

Bruce Stuart, 1908–11

Marty Walsh, 1911–12

Percy LeSueur, 1912–13[190]

Jack Darragh, 1916–19

Eddie Gerard, 1919–23

Cy Denneny, 1923–26

George Boucher, 1926–28

King Clancy, 1928–30

Frank Finnigan, 1930–31, 1932–33

Syd Howe, 1933–34

Sources:

- 1902–1934: Sportsecyclopedia.com.[191]

Team scoring leaders (NHL)

Note: Pos = Position; GP = Games Played; G = Goals; A = Assists; Pts = Points

| Player | Pos | GP | G | A | Pts |

| Cy Denneny | LW | 302 | 245 | 67 | 312 |

| Frank Nighbor | C | 326 | 134 | 60 | 194 |

| George Boucher | C/D | 332 | 118 | 50 | 168 |

| Hec Kilrea | RW | 293 | 104 | 56 | 160 |

| Frank Finnigan | RW | 363 | 96 | 57 | 153 |

| King Clancy | D | 305 | 85 | 65 | 150 |

| Punch Broadbent | RW | 150 | 85 | 27 | 112 |

| Bill Touhey | LW | 225 | 58 | 36 | 94 |

| Jack Darragh | LW | 120 | 68 | 21 | 89 |

| Eddie Gerard | LW | 128 | 50 | 30 | 80 |

Games: Frank Finnigan, 363

Penalty Minutes: George Boucher, 604

Goaltending Games: Alex Connell, 293

Goaltending Wins: Connell, 158

Shutouts: Connell, 70

Source: Total Hockey[192]

See also

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ottawa Hockey Club |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ottawa Senators. |

- History of the National Hockey League

- Ice hockey in Ottawa

- List of Stanley Cup champions

- List of ice hockey teams in Ontario

- Ottawa City Hockey League

- Ottawa Senators (FHL)

- Ottawa Senators (senior hockey)

- Ottawa Senators

- St. Louis Eagles

References

- Bibliography

Coleman, Charles L. (1966). The Trail of the Stanley Cup, Vol. 1, 1893–1926 inc. Montreal, Quebec: National Hockey League..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}