Genioglossus

| Genioglossus | |

|---|---|

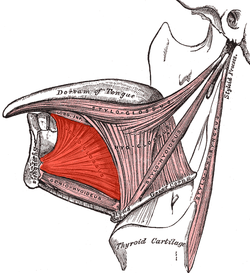

Extrinsic muscles of the tongue. Left side. | |

Muscles of the tongue from below, with genioglossus visible at top | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Superior part of mental spine of mandible (symphysis menti) |

| Insertion | Underside of tongue and body of hyoid |

| Artery | Lingual artery |

| Nerve | Hypoglossal nerve |

| Actions | Inferior fibers protrude the tongue, middle fibers depress the tongue, and its superior fibers draw the tip back and down |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus genioglossus |

| TA | A05.1.04.101 |

| FMA | 46690 |

Anatomical terms of muscle [edit on Wikidata] | |

The genioglossus is one of the paired extrinsic muscles of the tongue. The genioglossus is the major muscle responsible for protruding (or sticking out) the tongue.

Contents

1 Structure

2 Function

3 Clinical significance

4 History

5 References

6 External links

Structure

Genioglossus is the fan-shaped extrinsic tongue muscle that forms the majority of the body of the tongue. Its arises from the mental spine of the mandible and its insertions are the hyoid bone and the bottom of the tongue.[1][2]

The genioglossus is innervated by the hypoglossal nerve,[1] as are all muscles of the tongue except for the palatoglossus.[3] Blood is supplied to the sublingual branch of the lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid artery.[1][4]

The canine genioglossus muscle has been divided into horizontal and oblique compartments.[5]

Function

The left and right genioglossus muscles protruding the tongue and deviate it towards the opposite side. When acting together, the muscles depress the centre of the tongue at its back.[1]

Clinical significance

Contraction of the genioglossus stabilizes and enlarges the portion of the upper airway that is most vulnerable to collapse. Relaxation of the genioglossus and geniohyoideus muscles, especially during REM sleep, is implicated in obstructive sleep apnea.[6] Given this connection, the mandible can be pulled forward to maximise the airway space, and prevent the tongue from sinking backwards under anaesthesia and obstructing the airway.[1]

The genioglossus is often used as a proxy to test the function of the hypoglossal nerve, by asking a patient to stick out their tongue. Peripheral damage to the hypoglossal nerve can result in deviation of the tongue to the damaged side.[4]

History

The name derives from the Greek words γένειον (geneion) meaning chin, and γλῶσσα (glōssa) meaning tongue. The earliest recorded mention is by Helkiah Crooke in the early seventeenth century.[7]

References

^ abcde Susan Standring; Neil R. Borley; et al., eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 503–5. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Singh, Inderbir (2009). Essentials of anatomy (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Bros. p. 348. ISBN 978-81-8448-461-8.

^ M. J. T. Fitzgerald; Gregory Gruener; Estomih Mtui (2012). Clinical Neuroanatomy and Neuroscience. Saunders/Elsevier. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7020-4042-9.

^ ab Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 991–2. ISBN 978-0-443-06612-2.

^ Mu, Liancai; Sanders, Ira (2000). "Neuromuscular specializations of the pharyngeal dilator muscles: II. Compartmentalization of the canine genioglossus muscle". The Anatomical Record. 260 (3): 308–25. doi:10.1002/1097-0185(20001101)260:3<308::aid-ar70>3.0.co;2-n. PMID 11066041.

^ den Herder, Cindy; Schmeck, Joachim; Appelboom, Dick J K; de Vries, Nico (2004). "Risks of general anaesthesia in people with obstructive sleep apnoea". BMJ. 329 (7472): 955–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7472.955. PMC 524108. PMID 15499112.

^ "genioglossus - definition of genioglossus in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

External links

Anatomy figure: 34:02-01 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

"Anatomy diagram: 25420.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01.

- Frontal section