Venetian language

| Venetian | |

|---|---|

łéngoa vèneta, vèneto | |

| Native to | Italy, Slovenia, Croatia |

| Region |

|

Native speakers | 3.9 million (2002)[5] |

Language family | Indo-European

|

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | vec |

| Glottolog | vene1258[7] |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-n |

| |

A sign in Venetian reading "Here we also speak Venetian".

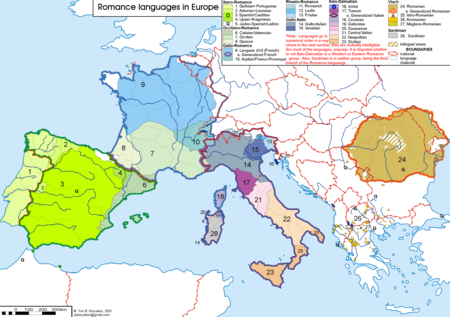

A map showing the distribution of Romance languages in Europe. Venetian is number 15.

Venetian[8][9] or Venetan[10][11] (Venetian: łéngoa vèneta or vèneto) is a Romance language spoken as a native language by almost four million people in the northeast of Italy,[12] mostly in the Veneto region of Italy, where most of the five million inhabitants can understand it, centered in and around Venice, which carries the prestige dialect. It is sometimes spoken and often well understood outside Veneto, in Trentino, Friuli, Venezia Giulia, Istria, and some towns of Slovenia, Dalmatia (Croatia), Brazil, Argentina and Mexico.

Although referred to as an Italian dialect (Venetian dialeto, Italian dialetto) even by its speakers, Venetian is a separate language with many local dialects. Its precise place within the Romance language family is controversial; see below

Contents

1 History

2 Geographic distribution

3 Classification

4 Regional variants

5 Grammar

5.1 Redundant subject pronouns

5.2 Interrogative inflection

5.3 Auxiliary verbs

5.4 Continuing action

5.5 Subordinate clauses

6 Phonology

6.1 Consonants

6.2 Vowels

7 Prosody

8 Sample etymological lexicon

9 Spelling systems

9.1 Traditional system

9.2 Proposed systems

10 Sample texts

10.1 Ruzante returning from war

10.2 Discorso de Perasto

10.3 Francesco Artico

11 Venetian lexical exports to English

12 See also

13 References

14 Bibliography

15 External links

History

Like all Italian dialects in the Romance language family, Venetian is descended from Vulgar Latin and influenced by the Italian language. Venetian is attested as a written language in the 13th century. There are also influences and parallelisms with Greek and Albanian in words such as pirón (fork), inpiràr (to fork), caréga (chair) and fanèla (T-shirt).

The language enjoyed substantial prestige in the days of the Venetian Republic, when it attained the status of a lingua franca in the Mediterranean. Notable Venetian-language authors include the playwrights Ruzante (1502–1542), Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793) and Carlo Gozzi (1720–1806). Following the old Italian theatre tradition (Commedia dell'Arte), they used Venetian in their comedies as the speech of the common folk. They are ranked among the foremost Italian theatrical authors of all time, and plays by Goldoni and Gozzi are still performed today all over the world.

Other notable works in Venetian are the translations of the Iliad by Casanova (1725–1798) and Francesco Boaretti, the translation of the Divine Comedy (1875) by Giuseppe Cappelli and the poems of Biagio Marin (1891–1985). Notable too is a manuscript titled Dialogue of Cecco di Ronchitti of Brugine about the New Star attributed to Girolamo Spinelli, perhaps with some supervision by Galileo Galilei for scientific details.[13]

Several Venetian-Italian dictionaries are available in print and online, including those by Boerio[14], Contarini[15], Nazari[16] and Piccio[17]

As a literary language, Venetian was overshadowed by Dante's Tuscan "dialect" (the best known writers of the Renaissance, such as Petrarch, Boccaccio and Machiavelli, were Tuscan and wrote in the Tuscan language) and languages of France like Occitan and the Oïl languages.

Even before the demise of the Republic, Venetian gradually ceased to be used for administrative purposes in favor of the Tuscan-derived Italian language that had been proposed and used as a vehicle for a common Italian culture, strongly supported by eminent Venetian humanists and poets, from Pietro Bembo (1470–1547), a crucial figure in the development of the Italian language itself, to Ugo Foscolo (1778–1827).

Virtually all modern Venetian speakers are diglossic with Italian. The present situation raises questions about the language's medium term survival. Despite recent steps to recognize it, Venetian remains far below the threshold of inter-generational transfer with younger generations preferring standard Italian in many situations. The dilemma is further complicated by the ongoing large-scale arrival of immigrants, who only speak or learn standard Italian.

Venetian spread to other continents as a result of mass migration from the Veneto region between 1870 and 1905, and 1945 and 1960. This itself was a by-product of the 1866 annexation, because the latter subjected the poorest sectors of the population to the vagaries of a newly integrated, developing national industrial economy centered on north-western Italy. Tens of thousands of peasants and craftsmen were thrown off their lands or out of their workshops, forced to seek better fortune overseas.

Venetian migrants created large Venetian-speaking communities in Argentina, Brazil (see Talian), and Mexico (see Chipilo Venetian dialect), where the language is still spoken today. Internal migrations under the Fascist regime also sent many Venetian speakers to other regions of Italy, like southern Lazio.

Currently, some firms have chosen to use the Venetian language in advertising as a famous beer did some years ago (Xe foresto solo el nome, "only the name is foreign").[18] In other cases advertisements in the Venice region are given a "Venetian flavour" by adding a Venetian word to standard Italian: for instance an airline used the verb xe (Xe sempre più grande, "it is always bigger") into an Italian sentence (the correct Venetian being el xe senpre più grando)[19] to advertise new flights from Marco Polo Airport[citation needed].

In 2007, Venetian was given recognition by the Veneto regional council with regional law n. 8 of 13 April 2007 "Protection, enhancement and promotion of the Veneto linguistic and cultural heritage".[20] Though the law does not explicitly grant Venetian any official status, it provides for Venetian as object of protection and enhancement, as an essential component of the cultural, social, historical and civil identity of Veneto.

Geographic distribution

Venetian is spoken mainly in the Italian regions of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and in both Slovenia and Croatia (Istria, Dalmatia and the Kvarner Gulf).[citation needed] Smaller communities are found in Lombardy, Trentino, Emilia-Romagna (in Mantua, Rimini, and Forlì), Sardinia (Arborea, Terralba, Fertilia), Lazio (Pontine Marshes), and formerly in Romania (Tulcea).

It is also spoken in North and South America by the descendants of Italian immigrants. Notable examples of this are Argentina and Brazil, particularly the city of São Paulo and the Talian dialect spoken in the Brazilian states of Espírito Santo, São Paulo, Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.

In Mexico, the Chipilo Venetian dialect is spoken in the state of Puebla and the town of Chipilo. The town was settled by immigrants from the Veneto region, and some of their descendants have preserved the language to this day. People from Chipilo have gone on to make satellite colonies in Mexico, especially in the states of Guanajuato, Querétaro, and State of Mexico. Venetian has also survived in the state of Veracruz, where other Italian migrants have settled from the late 1800s. The people of Chipilo preserve their dialect and call it chipileño and it has been preserved as a variant since the 19th century. The variant of the Venetan language spoken by the Cipiłàn (Chipileños) is northern Trevisàn-Feltrìn-Belumàt.

In 2009, the Brazilian city of Serafina Corrêa, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, gave Talian a joint official status alongside Portuguese.[21][22] Until the middle of the 20th century, Venetian was also spoken on the Greek Island of Corfu, which had long been under the rule of the Republic of Venice. Moreover, Venetian had been adopted by a large proportion of the population of Cephalonia, one of the Ionian Islands, because the island was part of the Stato da Màr for almost three centuries.[23]

Classification

Venetian is a Romance language and thus descends from Vulgar Latin. According to Tagliavini, it is one of the Italo-Dalmatian languages and most closely related to Istriot on the one hand and Tuscan–Italian on the other.[24] Some authors include it among the Gallo-Italic languages,[25] but by most authors, it is treated as separate from such Northern Italian group.[26] Typologically, Venetian has little in common with the Gallo-Italic languages of northwestern Italy, but shows some affinity to nearby Istriot.

Although the language region is surrounded by Gallo-Italic languages, Venetian does not share traits with these immediate neighbors. Scholars stress Venetian's characteristic lack of Gallo-Italic traits (agallicità)[27] or traits found further afield in Gallo-Romance languages (e.g. Occitan, French, Franco-Provençal)[28] or the Rhaeto-Romance languages (e.g. Friulian, Romansh). For example, Venetian did not undergo vowel rounding or nasalization, palatalize /kt/ and /ks/, or develop rising diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/, and it preserved final syllables, whereas, as in Italian, Venetian diphthongization occurs in historically open syllables.

Modern Venetian is not a close relative of the extinct Venetic language spoken in the Veneto region before Roman expansion, although both are Indo-European, and Venetic may have been an Italic language, like Latin, the ancestor of Venetian and most other languages of Italy. The earlier Venetic people gave their name to the city and region, which is why the modern language has a similar name.

Regional variants

The main regional varieties and subvarieties of the Venetian language outside of Venice are

Central (Padua, Vicenza, Polesine), with about 1,500,000 speakers.

Eastern/Coastal (Trieste, Grado, Istria, Fiume).

Western (Verona, Trentino).

North-Central Destra Piave of the Province of Treviso, most of the Province of Pordenone).

Northern Sinistra Piave of the Province of Treviso, (Belluno, comprising Feltre, Agordo, Cadore, Zoldo Alto).

All these variants are mutually intelligible, with a minimum 92% between the most diverging ones (Central and Western). Modern speakers reportedly can still understand Venetian texts from the 14th century to some extent.

Other noteworthy variants are:

- the variety spoken in Chioggia

- the variety spoken in the Pontine Marshes

- the variety spoken in Dalmatia

- the Talian dialect of Antônio Prado, Entre Rios, Santa Catarina and Toledo, Paraná, among other southern Brazilian cities.

- the Chipilo Venetian dialect (Spanish: Chipileño) of Chipilo, Mexico

- Peripheral creole languages along the southern border (nearly extinct).

Grammar

A street sign (nizioléto) in Venice using the Venetian calle, as opposed to the Italian via.

Lasa pur dir (Let them speak), an inscription on the Venetian House in Piran, southwestern Slovenia.

Like most Romance languages, Venetian has mostly abandoned the Latin case system, in favor of prepositions and a more rigid subject–verb–object sentence structure. It has thus become more analytic, if not quite as much as English. Venetian also has the Romance articles, both definite (derived from the Latin demonstrative ille) and indefinite (derived from the numeral unus).

Venetian also retained the Latin concepts of gender (masculine and feminine) and number (singular and plural). Unlike the Gallo-Iberian languages, which form plurals by adding -s, Venetian forms plurals in a manner similar to standard Italian. Nouns and adjectives can be modified by suffixes that indicate several qualities such as size, endearment, deprecation, etc. Adjectives (usually postfixed) and articles are inflected to agree with the noun in gender and number, but it is important to mention that the suffix might be deleted because the article is the part that suggests the number. However, Italian is influencing the Venetian language:

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

el gato graso | el gato graso | il gatto grasso | the fat (male) cat |

la gata grasa, | ła gata grasa, | la gatta grassa, | the fat (female) cat |

i gati grasi | i gati grasi | i gatti grassi | the fat (male) cats |

le gate grase | łe gate grase | le gatte grasse | the fat (female) cats |

Note that in recent studies on Venetian dialets in the Veneto, there has been a tendency to write the so-called "evanescent L" as ⟨ł⟩. While it may help novice speakers, Venetian was never written with this letter. In this article, this symbol is used only in Veneto dialects of the Venetian language. It will suffice to know that in the Venetian language the letter L in word-initial and intervocalic positions usually becomes a "palatal allomorph", and is barely pronounced.[29]

No native Venetic words seem to have survived in present Venetian, but there may be some traces left in the morphology, such as the morpheme -esto/asto/isto for the past participle, which can be found in Venetic inscriptions from about 500 BC:

Venetian: Mi go fazesto ("I have done")

Venetian Italian: Mi go fato

Standard Italian: Io ho fatto

Redundant subject pronouns

A peculiarity of Venetian grammar is a "semi-analytical" verbal flexion, with a compulsory "clitic subject pronoun" before the verb in many sentences, "echoing" the subject as an ending or a weak pronoun. Independent/emphatic pronouns (e.g. ti), on the contrary, are optional. The clitic subject pronoun (te, el/la, i/le) is used with the 2nd and 3rd person singular, and with the 3rd person plural. This feature may have arisen as a compensation for the fact that the 2nd- and 3rd-person inflections for most verbs, which are still distinct in Italian and many other Romance languages, are identical in Venetian.

The Piedmontese language also has clitic subject pronouns, but the rules are somewhat different. The function of clitics is particularly visible in long sentences, which do not always have clear intonational breaks to easily tell apart vocative and imperative in sharp commands from exclamations with "shouted indicative". For instance, in Venetian the clitic el marks the indicative verb and its masculine singular subject, otherwise there is an imperative preceded by a vocative. Although some grammars regard these clitics as "redundant", they actually provide specific additional information as they mark number and gender, thus providing number-/gender- agreement between the subject(s) and the verb, which does not necessarily show this information on its endings.

Interrogative inflection

Venetian also has a special interrogative verbal flexion used for direct questions, which also incorporates a redundant pronoun:

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

Ti geristu sporco? | (Ti) jèristu onto? or (Ti) xèrito spazo? | (Tu) eri sporco? | Were you dirty? |

El can, gerilo sporco? | El can jèreło onto? or Jèreło onto el can ? | Il cane era sporco? | Was the dog dirty? |

Ti te gastu domandà? | (Ti) te seto domandà? | (Tu) ti sei domandato? | Did you ask yourself? |

Auxiliary verbs

Reflexive tenses use the auxiliary verb avér ("to have"), as in English, Scandinavian, and Spanish; instead of èssar ("to be"), which would be normal in Italian. The past participle is invariable, unlike Italian:

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

Ti ti te ga lavà | (Ti) te te à/gà/ghè lavà | (Tu) ti sei lavato | You washed yourself |

(Lori) i se ga desmissià | (Lori) i se gà/à svejà | (Loro) si sono svegliati | They woke up |

Continuing action

Another peculiarity of the language is the use of the phrase eser drìo (literally, "to be behind") to indicate continuing action:

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

Me pare, el xe drìo parlàr | Mé pare 'l xe drìo(invià) parlàr | Mio padre sta parlando | My father is speaking |

Another progressive form in some Venetian dialects uses the construction essar là che (lit. "to be there that"):

- Venetian dialect: Me pare 'l è là che 'l parla (lit. "My father he is there that he speaks").

The use of progressive tenses is more pervasive than in Italian; E.g.

- English: "He wouldn't have been speaking to you".

- Venetian: No 'l saria miga sta drio parlarte a ti.

That construction does not occur in Italian: *Non sarebbe mica stato parlandoti is not syntactically valid.

Subordinate clauses

Subordinate clauses have double introduction ("whom that", "when that", "which that", "how that"), as in Old English:

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

Mi so de chi che ti parli | So de chi che te parla | So di chi parli | I know who you are talking about |

As in other Romance languages, the subjunctive mood is widely used in subordinate clauses.

| Venetian | Veneto dialects | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

Mi credeva che 'l fusse... | Credéa/évo che 'l fusse... | Credevo che fosse... | I thought he was... |

Phonology

Consonants

Labial | Dental/ Alveolar | Post alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

Plosive/ Affricate | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | |

voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||

Fricative | voiceless | f | s | |||

voiced | v | z | ||||

Approximant | central | j | ||||

lateral | l | |||||

Trill | r | |||||

Some dialects of Venetian have certain sounds not present in Italian, such as the interdental voiceless fricative [θ], often spelled with ⟨ç⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨zh⟩, or ⟨ž⟩, and similar to English th in thing and thought. This sound occurs, for example, in çéna ("supper", also written zhena, žena), which is pronounced the same as Castilian Spanish cena (which has the same meaning). The voiceless interdental fricative occurs in Bellunese, north-Trevisan, and in some Central Venetian rural areas around Padua, Vicenza and the mouth of the river Po.

Because the pronunciation variant [θ] is more typical of older speakers and speakers living outside of major cities, it has come to be socially stigmatized, and most speakers now use [s] or [ts] instead of [θ]. In those dialects with the pronunciation [s], the sound has fallen together with ordinary ⟨s⟩, and so it is not uncommon to simply write ⟨s⟩ (or ⟨ss⟩ between vowels) instead of ⟨ç⟩ or ⟨zh⟩ (such as sena).

Similarly some dialects of Venetian also have a voiced interdental fricative [ð], often written ⟨z⟩ (as in el pianze 'he cries'); but in most dialects this sound is now pronounced either as [dz] (Italian voiced-Z), or more typically as [z] (Italian voiced-S, written ⟨x⟩, as in el pianxe); in a few dialects the sound appears as [d] and may therefore be written instead with the letter ⟨d⟩, as in el piande.

Some varieties of Venetian also distinguish an ordinary [l] vs. a weakened or lenited ("evanescent") ⟨l⟩, which in some orthographic norms is indicated with the letter ⟨ł⟩; in more conservative dialects, however, both ⟨l⟩ and ⟨ł⟩ are merged as ordinary [l]. In those dialects that have both types, the precise phonetic realization of ⟨ł⟩ depends both on its phonological environment and on the dialect of the speaker. Typical realizations in the region of Venice include a voiced velar approximant or glide [ɰ] (usually described as nearly like an "e" and so often spelled as ⟨e⟩), when ⟨ł⟩ is adjacent (only) to back vowels (⟨a o u⟩), vs. a null realization when ⟨ł⟩ is adjacent to a front vowel (⟨i e⟩). A trill consonant sound frequently becomes a flap sound [ɾ] when occurring intervocalically.

In dialects further inland ⟨ł⟩ may be realized as a partially vocalised ⟨l⟩. Thus, for example, góndoła 'gondola' may sound like góndoea [ˈɡoŋdoɰa], góndola [ˈɡoŋdola], or góndoa [ˈɡoŋdoa]. In dialects having a null realization of intervocalic ⟨ł⟩, although pairs of words such as scóła, "school" and scóa, "broom" are homophonous (both being pronounced [ˈskoa]), they are still distinguished orthographically.

Venetian, like Spanish, does not have the geminate consonants characteristic of standard Italian, Tuscan, Neapolitan and other languages of southern Italy; thus Italian fette ("slices"), palla ("ball") and penna ("pen") correspond to féte, bała, and péna in Venetian. The masculine singular noun ending, corresponding to -o/-e in Italian, is often unpronounced in Venetian after continuants, particularly in rural varieties: Italian pieno ("full") corresponds to Venetian pien, Italian altare to Venetian altar. The extent to which final vowels are deleted varies by dialect: the central–southern varieties delete vowels only after /n/, whereas the northern variety delete vowels also after dental stops and velars; the eastern and western varieties are in between these two extremes.

The velar nasal [ŋ] (the final sound in English "song") occurs frequently in Venetian. A word-final /n/ is always velarized, which is especially obvious in the pronunciation of many local Venetian surnames that end in ⟨n⟩, such as Marin [maˈɾiŋ] and Manin [maˈniŋ], as well as in common Venetian words such as man ([ˈmaŋ] "hand"), piron ([piˈɾoŋ] "fork"). Moreover, Venetian always uses [ŋ] in consonant clusters that start with a nasal, whereas Italian only uses [ŋ] before velar stops: e.g. [kaŋˈtaɾ] "to sing", [iŋˈvɛɾno] "winter", [ˈoŋzaɾ] "to anoint", [ɾaŋˈdʒaɾse] "to cope with".[30]

Speakers of Italian generally lack this sound and usually substitute a dental [n] for final Venetian [ŋ], changing for example [maˈniŋ] to [maˈnin] and [maˈɾiŋ] to [maˈrin].

Vowels

Vowel sounds in Venetian are identical to the seven vowel sounds of standard Italian; [i, e, ɛ, a, ɔ, o, u].

Prosody

While written Venetian looks similar to Italian, it sounds very different, with a distinct lilting cadence, almost musical. Compared to Italian, in Venetian syllabic rhythms are more evenly timed, accents are less marked, but on the other hand tonal modulation is much wider and melodic curves are more intricate. Stressed and unstressed syllables sound almost the same; there are no long vowels, and there is no consonant lengthening. Compare the Italian sentence "va laggiù con lui" [go there with him] (long-short-long-short-long syllables) with Venetian "va là zo co lu" (all short syllables).[31]

Sample etymological lexicon

As a direct descent of regional spoken Latin, the Venetian lexicon derives its vocabulary substantially from Latin and (in more recent times) from Tuscan, so that most of its words are cognate with the corresponding words of Italian. Venetian includes however many words derived from other sources (such as Greek, Gothic, and German) that are not cognate with their equivalent words in Italian, such as:

| Venetian | English | Italian | Venetian word origin |

|---|---|---|---|

uncò, 'ncò, incò, ancò, ancùo, incoi | today | oggi | from Latin hunc + hodie |

apotèca | pharmacy | farmacia | from Ancient Greek ἀποθήκη (apothḗkē) |

trincàr | to drink | bere | from German trinken "to drink" |

armelìn | apricot | albicocca | from Latin armenīnus |

astiàr | to bore | dare noia, seccare | from Gothic 𐌷𐌰𐌹𐍆𐍃𐍄𐍃, haifsts meaning "contest" |

bagìgi | peanuts | arachidi | from Arabic habb-ajiz |

becàr | to be spicy hot | essere piccante | from Italian beccare, literally "to peck" |

bìgolo | spaghetti | vermicello, spaghetti | from Latin (bom)byculus |

bisàto, bisàta | eel | anguilla | from Latin bestia "beast", compare also Italian biscia, a kind of snake |

bìssa, bìsso | snake | serpente | from Latin bestia "beast", compare also Ital. biscia, a kind of snake |

bìsi | peas | piselli | related to the Italian word |

isarda, risardola | lizard | lucertola | from Latin lacertus, same origin as English lizard |

trar via | to throw | tirare | local cognate of Italian tirare |

calìgo | fog | nebbia foschia | from Latin caligo |

cantón | corner/side | angolo/parte | from Latin cantus |

catàr | find + take | trovare + prendere | from Latin adcaptare |

caréga, trón | chair | sedia | from Latin cathedra and thronus (borrowings from Greek) |

ciao | hello, goodbye | ciao | from Venetian s-ciao "slave", from Medieval Latin sclavus |

ciapàr | to catch, to take | prendere | from Latin capere |

co | when (non-interr.) | quando | from Latin cum |

copàr | to kill | uccidere | from Old Italian accoppare, originally "to behead" |

carpéta | miniskirt | minigonna | compare English carpet |

còtoła | skirt | sottana | from Latin cotta, "coat, dress" |

fanèla | T-shirt | maglietta | borrowing from Greek |

gòto, bicèr | drinking glass | bicchiere | from Latin guttus, "cruet" |

insìa | exit | uscita | from Latin in + exita |

mi | I | io | from Latin me ("me", accusative case); Italian io is derived from the Latin nominative form ego |

massa | too much | troppo | from Greek μᾶζα (mâza) |

morsegàr, smorsegàr | to bite | mordere | derverbal derivative, from Latin morsus "bitten", compare Italian morsicare |

mustaci, mostaci | moustaches | baffi | from Greek μουστάκι (moustaki) |

munìn, gato, gatìn | cat | gatto | perhaps onomatopoeic, from the sound of a cat's meow |

meda | big sheaf | grosso covone | from messe, mietere, compare English meadow |

musso | donkey | asino | from Latin almutia "horses eye binders (cap)" (compare Provençal almussa, French aumusse) |

nòtoła, notol, barbastrìo, signàpoła | bat | pipistrello | derived from not "night" (compare Italian notte) |

pantegàna | rat | ratto | from Slovene podgana |

pinciàr | beat, cheat, sexual intercourse | imbrogliare, superare in gara, amplesso | from French pincer (compare English pinch) |

pirón | fork | forchetta | from Greek πιρούνι (piroúni) |

pisalet | dandelion | tarassaco | from French pissenlit |

plao far | truant | marinare scuola | from German blau machen |

pomo/pón | apple | mela | from Latin pomus |

sbregàr | to break, to shred | strappare | from Gothic 𐌱𐍂𐌹𐌺𐌰𐌽 (brikan), related to English to break and German brechen |

schèi | money | denaro soldi | from German Scheidemünze |

saltapaiusc | grasshopper | cavalletta | from salta "hop" + paiusc "grass" (Italian paglia) |

sghiràt, schirata, skirata | squirrel | scoiattolo | Related to Italian word, probably from Greek σκίουρος (skíouros) |

sgnapa | spirit from grapes, brandy | grappa acquavite | from German Schnaps |

sgorlàr, scorlàr | to shake | scuotere | from Latin ex + crollare |

sina | rail | rotaia | from German Schiene |

straco | tired | stanco | from Lombard strak |

strica | line, streak, stroke, strip | linea, striscia | from the proto-Germanic root *strik, related to English streak, and stroke (of a pen). Example: Tirar na strica "to draw a line". |

strucàr | to press | premere, schiacciare | from proto-Germanic *þrukjaną ('to press, crowd') through the Gothic or Langobardic language, related to Middle English thrucchen ("to push, rush"), German drücken ('to press'), Swedish trycka. Example: Struca un tasto / boton "Strike any key / Press any button". |

supiàr, subiàr, sficiàr, sifolàr | to whistle | fischiare | from Latin sub + flare, compare French siffler |

tòr su | to pick up | raccogliere | from Latin tollere |

técia, téia, tegia | pan | pentola | from Latin tecula |

tosàt(o) (toxato), fio | lad, boy | ragazzo | from Italian tosare, "to cut someone's hair" |

puto, putèło, putełeto, butèl | lad, boy | ragazzo | from Latin puer, putus |

matelot | lad, boy | ragazzo | perhaps from French matelot, "sailor" |

vaca | cow | mucca, vacca | from Latin vacca |

s-ciop, s-ciòpo, s-ciopàr, s-ciopón | gun | fucile-scoppiare | from Latin scloppum (onomatopoeic) |

troi | track path | sentiero | from Latin trahere, "to draw, pull", compare English track |

zavariàr | to worry | preoccuparsi, vaneggiare | from Latin variare |

Spelling systems

Traditional system

Venetian does not have an official writing system, but it is traditionally written using the Latin script — sometimes with certain additional letters or diacritics. The basis for some of these conventions can be traced to Old Venetian, while others are purely modern innovations.

Medieval texts, written in Old Venetian, include the letters ⟨x⟩, ⟨ç⟩ and ⟨z⟩ to represent sounds that do not exist or have a different distribution in Italian. Specifically:

- The letter ⟨x⟩ was often employed in words that nowadays have a voiced /z/-sound (compare English xylophone); for instance ⟨x⟩ appears in words such as raxon, Croxe, caxa ("reason", "(holy) Cross" and "house"). The precise phonetic value of ⟨x⟩ in Old Venetian texts remains unknown, however.

- The letter ⟨z⟩ often appeared in words that nowadays have a varying voiced pronunciation ranging from /z/ to /dz/ or /ð/ or even to /d/; even in contemporary spelling zo "down" may represent any of /zo, dzo, ðo/ or even /do/, depending on the dialect; similarly zovena "young woman" could be any of /ˈzovena/, /ˈdzovena/ or /ˈðovena/, and zero "zero" could be /ˈzɛro/, /ˈdzɛro/ or /ˈðɛro/.

- Likewise, ⟨ç⟩ was written for a voiceless sound which now varies, depending on the dialect spoken, from /s/ to /ts/ to /θ/, as in for example dolçe "sweet", now /ˈdolse ~ ˈdoltse ~ ˈdolθe/, dolçeça "sweetness", now /dolˈsesa ~ dolˈtsetsa ~ dolˈθeθa/, or sperança "hope", now /speˈransa ~ speˈrantsa ~ speˈranθa/.

The usage of letters in medieval and early modern texts was not, however, entirely consistent. In particular, as in other northern Italian languages, the letters ⟨z⟩ and ⟨ç⟩ were often used interchangeably for both voiced and voiceless sounds. Differences between earlier and modern pronunciation, divergences in pronunciation within the modern Venetian-speaking region, differing attitudes about how closely to model spelling on Italian norms, as well as personal preferences, some of which reflect sub-regional identities, have all hindered the adoption of a single unified spelling system.[32]

Nevertheless, in practice, most spelling conventions are the same as in Italian. In some early modern texts letter ⟨x⟩ becomes limited to word-initial position, as in xe ("is"), where its use was unavoidable because Italian spelling cannot represent /z/ there. In between vowels, the distinction between /s/ and /z/ was ordinarily indicated by doubled ⟨ss⟩ for the former and single ⟨s⟩ for the latter. For example, basa was used to represent /ˈbaza/ ("he/she kisses"), whereas bassa represented /ˈbasa/ ("low"). (Before consonants there is no contrast between /s/ and /z/, as in Italian, so a single ⟨s⟩ is always used in this circumstance, it being understood that the ⟨s⟩ will agree in voicing with the following consonant. For example, ⟨st⟩ represents only /st/, but ⟨sn⟩ represents /zn/.)

Traditionally the letter ⟨z⟩ was ambiguous, having the same values as in Italian (both voiced and voiceless affricates /dz/ and /ts/). Nevertheless, in some books the two pronunciations are sometimes distinguished (in between vowels at least) by using doubled ⟨zz⟩ to indicate /ts/ (or in some dialects /θ/) but a single ⟨z⟩ for /dz/ (or /ð/, /d/).

In more recent practice the use of ⟨x⟩ to represent /z/, both in word-initial as well as in intervocalic contexts, has become increasingly common, but no entirely uniform convention has emerged for the representation of the voiced vs. voiceless affricates (or interdental fricatives), although a return to using ⟨ç⟩ and ⟨z⟩ remains an option under consideration.

Regarding the spelling of the vowel sounds, because in Venetian, as in Italian, there is no contrast between tense and lax vowels in unstressed syllables, the orthographic grave and acute accents can be used to mark both stress and vowel quality at the same time: à /a/, á /ɐ/, è /ɛ/, é /e/, ò /ɔ/, ó /o/, ù /u/. Different orthographic norms prescribe slightly different rules for when stressed vowels must be written with accents or may be left unmarked, and no single system has been accepted by all speakers.

Venetian allows the consonant cluster /stʃ/ (not present in Italian), which is sometimes written ⟨s-c⟩ or ⟨s'c⟩ before i or e, and ⟨s-ci⟩ or ⟨s'ci⟩ before other vowels. Examples include s-ciarir (Italian schiarire, "to clear up"), s-cèt (schietto, "plain clear"), s-ciòp (schioppo, "gun") and s-ciao (schiavo, "[your] servant", ciao, "hello", "goodbye"). The hyphen or apostrophe is used because the combination ⟨sc(i)⟩ is conventionally used for the /ʃ/ sound, as in Italian spelling; e.g. scèmo (scemo, "stupid"); whereas ⟨sc⟩ before a, o and u represents /sk/: scàtoła (scatola, "box"), scóndar (nascondere, "to hide"), scusàr (scusare, "to forgive").

Proposed systems

Recently there have been attempts to standardize and simplify the script by reusing older letters, e.g. by using ⟨x⟩ for [z] and a single ⟨s⟩ for [s]; then one would write baxa for [ˈbaza] ("[third person singular] kisses") and basa for [ˈbasa] ("low"). Some authors have continued or resumed the use of ⟨ç⟩, but only when the resulting word is not too different from the Italian orthography: in modern Venetian writings, it is then easier to find words as çima and çento, rather than força and sperança, even though all these four words display the same phonological variation in the position marked by the letter ⟨ç⟩. Another recent convention is to use ⟨ł⟩ for the "soft" l, to allow a more unified orthography for all variants of the language. However, in spite of their theoretical advantages, these proposals have not been very successful outside of academic circles, because of regional variations in pronunciation and incompatibility with existing literature.

The Venetian speakers of Chipilo use a system based on Spanish orthography, even though it does not contain letters for [j] and [θ]. The American linguist Carolyn McKay proposed a writing system for that variant, based entirely on the Italian alphabet. However, the system was not very popular.

Sample texts

Ruzante returning from war

The following sample, in the old dialect of Padua, comes from a play by Ruzante (Angelo Beolco), titled Parlamento de Ruzante che iera vegnù de campo ("Dialogue of Ruzante who came from the battlefield", 1529). The character, a peasant returning home from the war, is expressing to his friend Menato his relief at being still alive:

Orbéntena, el no serae mal | "Really, it would not be that bad |

Discorso de Perasto

The following sample is taken from the Perasto Speech (Discorso de Perasto), given on August 23, 1797 at Perasto, by Venetian Captain Giuseppe Viscovich, at the last lowering of the flag of the Venetian Republic (nicknamed the "Republic of Saint Mark").

Par trezentosetantasete ani | "For three hundred and seventy seven years |

Francesco Artico

The following is a contemporary text by Francesco Artico. The elderly narrator is recalling the church choir singers of his youth, who, needless to say, sang much better than those of today:

Sti cantori vèci da na volta, | "These old singers of the past, |

Venetian lexical exports to English

Many words were exported to English, either directly or via Italian or French.[33] The list below shows some examples of imported words, with the date of first appearance in English according to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.

| Venetian | English | Year | Origin, notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| arsenal | arsenal | 1506 | Arabic دار الصناعة dār al-ṣināʻah "house of manufacture, factory" |

| articioco | artichoke | 1531 | Arabic الخرشوف al-kharshūf; simultaneously entered French as artichaut |

| balota | ballot | 1549 | ball used in Venetian elections; cf. English to "black-ball" |

| casin | casino | 1789 | "little house"; adopted in Italianized form |

| schiao | ciao | 1929 | cognate with Italian schiavo "slave"; used originally in Venetian to mean "your servant", "at your service"; original word pron. "s-ciao" |

| contrabando | contraband | 1529 | illegal traffic of goods |

| gazeta | gazette | 1605 | a small Venetian coin; from the price of early newssheets gazeta de la novità "a penny worth of news" |

| gheto | ghetto | 1611 | from Gheto, the area of Canaregio in Venice that became the first district confined to Jews; named after the foundry or gheto once sited there |

| ziro | giro | 1896 | "circle, turn, spin"; adopted in Italianized form; from the name of the bank Banco del Ziro or Bancoziro at Rialto |

| gnochi | gnocchi | 1891 | lumps, bumps, gnocchi; from Germanic knokk- 'knuckle, joint' |

| gondola | gondola | 1549 | from Medieval Greek κονδοῦρα |

| laguna | lagoon | 1612 | Latin lacunam "lake" |

| lazareto | lazaret | 1611 | through French; a quarantine station for maritime travellers, ultimately from the Biblical Lazarus of Bethany, who was raised from the dead; the first one was on the island of Lazareto Vechio in Venice |

| lido | lido | 1930 | Latin litus "shore"; the name of one of the three islands enclosing the venetian lagoon, now a beach resort |

| loto | lotto | 1778 | Germanic lot- "destiny, fate" |

| malvasìa | malmsey | 1475 | ultimately from the name μονοβασία Monemvasia, a small Greek island off the Peloponnese once owned by the Venetian Republic and a source of strong, sweet white wine from Greece and the eastern Mediterranean |

| marzapan | marzipan | 1891 | from the name for the porcelain container in which marzipan was transported, from Arabic موثبان mawthabān, or from Mataban in the Bay of Bengal where these were made (these are some of several proposed etymologies for the English word) |

| Negroponte | Negroponte | "black bridge"; Greek island called Euboea or Evvia in the Aegean Sea | |

| Montenegro | Montenegro | "black mountain"; country on the Eastern side of the Adriatic Sea | |

| Pantalon | pantaloon | 1590 | a character in the Commedia dell'arte |

| pestachio | pistachio | 1533 | ultimately from Middle Persian pistak |

| quarantena | quarantine | 1609 | forty day isolation period for a ship with infectious diseases like plague |

| regata | regatta | 1652 | originally "fight, contest" |

| scampi | scampi | 1930 | Greek κάμπη "caterpillar", lit. "curved (animal)" |

| zechin | sequin | 1671 | Venetian gold ducat; from Arabic سكّة sikkah "coin, minting die" |

| Zani | zany | 1588 | "Johnny"; a character in the Commedia dell'arte |

See also

- Venetian literature

- Talian dialect

- Chipilo Venetian dialect

Quatro Ciàcoe — Venetian language magazine

References

^ abc United Nations (1991). Fifth United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names: Vol.2. Montreal..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc Holmes, Douglas R., (1989). Cultural disenchantments: worker peasantries in northeast Italy. Princeton University Press.

^ Minahan, James (1998). Miniature empires: a historical dictionary of the newly independent states. Westport: Greenwood.

^ Kalsbeek, Janneke (1998). The Čakavian dialect of Orbanići near Žminj in Istria. Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics. 25. Atlanta.

^ Venetian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

^ Aprovado projeto que declara o Talian como patrimônio do RS Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine., accessed on 21 August 2011

^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Venetian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

^ "Glottolog 3.3 - Venetian". glottolog.org. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

^ "Venetian". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

^ "Linguasphere - Venetan" (PDF). linguasphere.info. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

^ "Indo-european phylosector, Linguasphere" (PDF).

^ Ethnologue

^ "Dialogo de Cecco Di Ronchitti da Bruzene in perpuosito de la stella nuova". Unione Astrofili Italiani.

^ Boerio, Giuseppe (1856). Dizionario del dialetto veneziano. Venezia: Giovanni Cecchini.

^ Contarini, Pietro (1850). Dizionario tascabile delle voci e frasi particolari del dialetto veneziano. Venezia: Giovanni Cecchini.

^ Nazari, Giulio (1876). Dizionario Veneziano-Italiano e regole di grammatica. Belluno: Arnaldo Forni.

^ Piccio, Giuseppe (1928). Dizionario Veneziano-Italiano. Venezia: Libreria Emiliana.

^ "Forum Nathion Veneta". Retrieved 15 October 2015.

^ Right spelling, according to: Giuseppe Boerio, Dizionario del dialetto veneziano, Venezia, Giovanni Cecchini, 1856.

^ Regional Law no. 8 of 13 April 2007. "Protection, enhancement and promotion of the Veneto linguistic and cultural heritage"

^ "Vereadores aprovam o talian como língua co-oficial do município" [Councilors approve talian as co-official language of the municipality]. serafinacorrea.rs.gov.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 21 August 2011.

^ "Talian em busca de mais reconhecimento" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

^ Kendrick, Tertius T. C. (1822). The Ionian islands: Manners and customs. London: J. Haldane. p. 106.

^ Tagliavini, Carlo (1948). Le origini delle lingue Neolatine: corso introduttivo di filologia romanza. Bologna: Pàtron.

^ Haller, Hermann W. (1999). The other Italy: the literary canon in dialect. University of Toronto Press.

^ Renzi, Lorenzo (1994). Nuova introduzione alla filologia romanza. Bologna: Il Mulino. p. 176.I dialetti settentrionali formano un blocco abbastanza compatto con molti tratti comuni che li accostano, oltre che tra loro, qualche volta anche alla parlate cosiddette ladine e alle lingue galloromanze ... Alcuni fenomeni morfologici innovativi sono pure abbastanza largamente comuni, come la doppia serie pronominale soggetto (non sempre in tutte le persone) ... Ma più spesso il veneto si distacca dal gruppo, lasciando così da una parte tutti gli altri dialetti, detti gallo-italici.

^ Alberto Zamboni (1988:522)

^ Giovan Battista Pellegrini (1976:425)

^ Tomasin, Lorenzo (2010), La cosiddetta “elle evanescente” del veneziano: fra dialettologia e storia linguistica (PDF), Palermo: Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani

^ Zamboni, Alberto (1975). Cortelazzo, Manlio, ed. Veneto [Venetian language]. Profilo dei dialetti italiani (in Italian). 5. Pisa: Pacini. p. 12.b) n a s a l i: esistono, come nello 'standard', 3 fonemi, /m/, /n/, /ń/, immediatamente identificabili da /mása/ 'troppo' ~ /nása/ 'nasca'; /manáse/ 'manacce' ~ /mańáse/ 'mangiasse', ecc., come, rispettivamente, bilabiale, apicodentale, palatale; per quanto riguarda gli allòfoni e la loro distribuzione, è da notare [ṅ] dorsovelare, cfr. [áṅka] 'anche', e, regolarmente in posizione finale: [parọ́ṅ] 'padrone', [britoíṅ] 'temperino': come questa, è caratteristica v e n e t a la realizzazione velare anche davanti a cons. d'altro tipo, cfr. [kaṅtár], it. [kantáre]; [iṅvę́rno], it. [iɱvę́rno]; [ọ́ṅʃar] 'ungere', [raṅǧárse], it. [arrańǧársi], ecc.

^ Ferguson 2007, p. 69-73.

^ Ursini, Flavia (2011). Dialetti veneti. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/dialetti-veneti_(Enciclopedia-dell'Italiano)/

^ Ferguson 2007, p. 284-286.

Bibliography

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

Artico, Francesco (1976). Tornén un pas indrìo: raccolta di conversazioni in dialetto. Brescia: Paideia Editrice.

Ferguson, Ronnie (2007). A Linguistic History of Venice. Firenze: Leo S. Olschki. ISBN 978-88-222-5645-4.

McKay, Carolyn Joyce. Il dialetto veneto di Segusino e Chipilo: fonologia, grammatica, lessico veneto, spagnolo, italiano, inglese.

External links

Venetian edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Venetian Wikisource has original text related to this article: Vèneto |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Venetian language. |

- General grammar; comparison to other Romance languages; description of the Venetian dialect

Tornén un pas indrìo!—samples of written and spoken Venetian by Francesco Artico- Text and audio of some works by Ruzante